Over several generations this small part of urban Australia has attracted writers, artists and photographers eager to find needed inspiration and stimulation. Most Sydneysiders and millions of tourists would know The Rocks as a historic precinct in which it is possible to have a good night out while enjoying the ambience of a genuine nineteenth-century townscape replete with historic pubs, tiny workers’ cottages, handsome terraces, inviting eateries, pocket parks and cobbled laneways – all within a stone’s throw of the harbour and the CBD.

Why did the whole Rocks saga become front-page news? Because it involved the mass refusal by an army of determined unionists to apply their labour to an unpopular development proposal, and because it was a catalyst, a unifying event, an extraordinary and unprecedented moment for public sentiment to emerge as a driving force for reform of outdated planning laws and the introduction of heritage conservation as a proper responsibility of government.

In 1960, the state government under Labor Premier Heffron invited selected developer teams to submit fresh proposals for reshaping the area east of the expressway, right down to the harbour’s edge. Once again, big changes were looming. In January 1964, the construction firm of James Wallace Pty Ltd was named the successful tenderer on the basis of a scheme prepared by leading Sydney architects Edwards Madigan and Torzillo. From the harbourside at Dawes Point as far south as the Cahill Expressway, the old Rocks would be replaced by high-rise office towers, retail and commercial space, and some 13 residential apartment blocks linked by a continuous traffic-free podium element at ground level.

The Wallace–EMT scheme did not proceed under the new conservative state government that was elected in May 1965. But the building boom in Sydney was moving into top gear and a year later the prospect of wholesale redevelopment again appeared when Liberal Premier Bob Askin sought the advice of John Overall, Commissioner of Canberra’s National Capital Development Commission (NCDC). On the ground, little had changed. The Askin Government saw a large, rundown yet extremely valuable area of public land occupying a prime harbourside position on the edge of the CBD. Yes, it was occupied, but only by a handful of low-income state tenants, slum dwellers, hippies, down-and-outers and families on the welfare housing list paying ridiculously low rents. The government’s position was clear: in the name of progress they would have to go.

As with the abandoned Wallace scheme, the government’s ultimate objective was to enable the huge real-estate potential of the area to be unlocked and exploited to the full.

In June 1967, Overall presented his Observations on Redevelopment of the Western Side of Sydney Cove Rocks Area to Grosvenor Street to the NSW Parliament.

John Overall was an architect, ex-military commander, and a very capable public servant. He brought these attributes to his Rocks assignment in full measure. Overall’s recommendation was the state government create a dedicated agency to undertake the redevelopment of The Rocks.

The Rocks, 1970 scheme as adopted by the NSW government.

Image: Sydney Harbour Foreshore Authority

The state government’s decision to create a special authority [to develop The Rocks] was shortly followed by the impetuous passing in January of the Sydney Cove Redevelopment Act 1968. Public debate on the bill was not on the agenda and press coverage was minimal. Two years later, in January 1970 the Sydney Cove Redevelopment Authority (SCRA) was established. The authority’s first executive director and deputy chair was DO (Owen) Magee BE FIE, an ex-military man whose field rank as a recently retired Brigadier was prominently and proudly noted on the back cover of his 2005 memoir. Obviously a no-nonsense operator, there could be no better man for the job. Under Magee, the SCRA quickly appointed a consortium of consultants led by Melbourne architects Bates Smart and McCutcheon, with a brief to review the Overall scheme and present a detailed set of proposals to the government within a year. In December 1970 they delivered, and their scheme was promptly adopted. The SCRA was in business.

The commission’s brief was to accelerate the design and construction of the new capital, a project that had been languishing since the 1930s. Engaging with newly arrived residents in the territory would have been pointless, but The Rocks was a different story. Here was a mature community with a long memory and long-standing associations with an area it had come to love. In the case of the SCRA scheme and its Melbourne-based architects, the tight schedule set by the government virtually ruled out any serious consultation. For this high-powered consortium, the prospect of community participation would have been dismissed as an expensive and time-consuming diversion. Weren’t the majority of residents low-income public housing tenants, slumdwellers? What right did they have to influence or interfere with a multimillion-dollar urban renewal project designed to clean up, once and for all, this crumbling and ramshackle quarter that was disfiguring the site of the nation’s birthplace?

There can be no doubt that for Magee, and presumably for the Authority, there was no love lost when it came to its later dealings with the Rocks Resident Action Group, professional institutes, including the Royal Australian Planning Institute (RAPI), the Royal Australian Institute of Architects (RAIA), and the BLF. Magee’s colourful language in his chapter on the “Riots in the Rocks” makes it abundantly clear that for him at least, the unionists were “thugs,” “a mob” of “screaming rioters” and “conspirators,” “drunkards,” members of a “power-mad” union intent on “rule by violence.” Bob Pringle and Jack Mundey were “henchmen,” promoting the “power of the proletariat” and their “ruthless” desire for “worker control.” The NSW parliament had given the Authority unprecedented powers at a time when town planning legislation was primitive, when there was no statutory protection for heritage, and when a right-wing conservative government was in no mood to have its plans derailed by resident activists, left-wing unionists, or their misguided allies in the design professions.

There may also have been a disinclination – or even a directive – to avoid dealing with those local design professionals. For reasons unknown, Magee’s book ignores the institutes of planning and architecture, despite the evidence that the RAPI and RAIA had significant concerns about the 1970 scheme and both institutes made formal submissions to the Authority setting out those oncerns. Both bodies also achieved something that eluded the Authority at the time: the development of a mutually respectful working relationship with Jack Mundey and other BLF leaders as well as with the residents’ action group.

The Rocks, George Street North as it might have been under the 1970 scheme.

Image: Sydney Harbour Foreshore Authority

The SCRA scheme was founded on the expectation that it would be a model – a demonstration – of what could be achieved when the crème de la crème of the country’s design consultants, project managers, land economists, traffic engineers and real estate brains were brought together to determine a profitable future for this very valuable piece of publicly owned property. Overseas precedents such as La Défense in Paris and The Barbican scheme in London were examined in the field during a whirlwind study tour that Magee and architect Walter Bunning made shortly after the former’s appointment as executive director. The resulting design was a cluster of brutalist tower blocks stepping down the ridge to the harbour’s edge and ranging in height from 30 to 50 storeys, accommodating offices, retail uses, luxury hotels and apartments. A labyrinthine system of underground car parks made sure that motorists would not be inconvenienced. The heritage lobby was placated by including the retention (or relocation) of a handful of historic buildings, mainly in the northern sector. The government summarily adopted the scheme after a token public exhibition, and its implementation was promptly authorised in December 1970. This was probably seen by the Authority as an auspicious time to release such a potentially controversial scheme, given the holiday period. In February the plans were officially launched, and briefly put on public display.

Rumours of impending evictions and loss of tenant rights, such as they were, led swiftly to the formation of The Rocks Resident Action Group. Their leader was Nita McRae, third generation Rocks resident and mother. In November 1971 the group approached BLF secretary Jack Mundey and president Bob Pringle seeking union help. A green ban was placed, and the battle for The Rocks was about to get underway.

In The Rocks, the welfare and housing needs of hundreds of low-income public housing tenants were among the primary drivers. Loss of heritage and history was another. As for the wider public – and a growing cohort of concerned professionals, civic leaders, ‘ordinary folk’ – there was a palpable feeling of outrage at the cavalier way a state government could comfortably accept these architecturally audacious schemes without any attempt to assess public opinion. Almost half a century on, the contemporary observer familiar with the human scale and undeniable charm of this mid-Victorian townscape could be excused for failing to understand what was being proposed at the time. The archives say it all. Many historic properties from Grosvenor Street north towards the harbour were to be razed and replaced by massive tower blocks, concrete plazas, podiums. Modern architecture was to be given free rein in this special place – all in the name of slum clearance and “urban renewal”.

In simple terms, the BLF’s green ban led by Mundey and Pringle proved to be the kiss of death for the official SCRA scheme that had been so enthusiastically adopted by the Askin Government. The ban provided a breathing space for residents and supporters from outside to consider their options. It encouraged The Rocks community to work with a group of interested professionals in the preparation of a people’s plan for their historic turf, a project that came to naught in bricks-and-mortar terms but would indirectly influence the review of the SCRA scheme, which eventually, and perhaps reluctantly, was commissioned in 1974. The revised scheme signalled a significant volte-face for the Authority. From that time on there would be no going back to wall-to-wall high-rise office towers, luxury housing for the fortunate few, a few tokenistic nods in the direction of the heritage lobby.

To close the circle, the chair of the Sydney Harbour Foreshore Authority officially opened Jack Mundey Place in The Rocks on 1 May 2009. Within a stone’s throw of the setting for the bulldozer charges, bashings, sit-ins, lockouts and arrests of the early 1970s, Mike Collins named a small piece of the city after the man who began the conservation process during that turbulent period:

All movements need leadership, and this one found a dynamic and charismatic leader in Jack Mundey. He was the right leader at the right time … the movement that he led here at The Rocks was the genesis of Green Bans, and part of rethinking of planning and heritage in New South Wales … there is therefore a direct lineage between the protests that Jack led here and the birth of regulated heritage preservation around Australia.

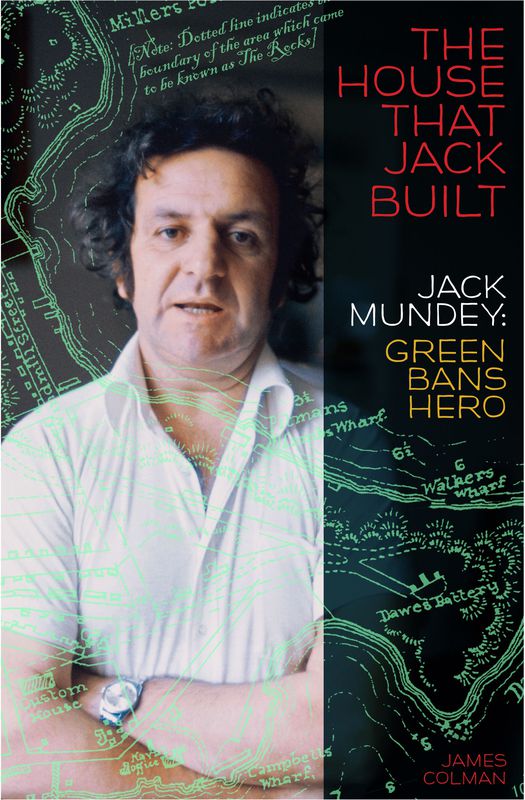

The House That Jack Built by James Colman is published by NewSouth Publishing.