In November 2022, Kerstin Thompson curated a Design Speaks symposium called “A Broader Landscape” alongside Phillip Arnold.1 The curators asked how architects understand the word “landscape,” and how else they might understand it. The symposium drew forth an understanding of landscape that went beyond its aesthetic appeal as scenery, toward an idea that is a defining force in Thompson’s decision-making – that landscape is also the site of life.

In fact, Thompson writes in Leon van Schaik’s monograph on her practice, “I think site and architecture exist in a continuum with their situation, part of a series, of a collection, contributing to a contiguous whole. There are two aspects to this: the first is to do with buildings as part of a greater composite; the second is to do with an ecological integrity. Both acknowledge the interconnectivity and interdependence of architecture with site and situation.”2

Thompson’s architectural processes bring together experiential concerns of building with considerations of place. The relationship made with landscape in its scenic understanding is defined throughout the work from within and without: low horizontal forms, buried or partially embedded buildings, landscaped settings, and deep verandahs overlapping the internal/external threshold.

Increasingly, Thompson’s understanding of place includes modes of landscape architecture and ecology, so that the structural and formal responses are shaped by the way that the building can participate in the site’s ecosystem across multiple scales. This is expressed with a straightforwardness that is surprisingly uncommon in architecture generally, such as buildings that can flood and buildings that allow water to move underneath. These moves represent a simple yet profound reckoning with a building’s physicality that is rarely made on the terms of the ecosystem.

The straightforwardness in resolution comes from a sophistication in the way Thompson integrates the ecological intentions with the experiential, connecting the use and user to the place in ways that bridge the nature/culture divide. One is embedded, elevated, transported around, and “held” in these places that overlap the cultural and ecological. She shows us how we might understand landscape in regard to architecture.

Buildings are typically incompatible with ecological integrity, conservation and ecosystem repair either at their sites or in the larger landscape beyond the “boundary” – not to mention their extractive beginnings, energy-intensive lives and wasteful endings. As we learn how buildings could play a part in repairing ecosystems, beyond a picturesque response to landscape, much of Thompson’s architecture offers deeply convincing guidance. Two examples in particular resonate: the new buildings at Bundanon Art Museum and Bridge and the (shortlisted) design competition entry for the Shepparton Art Museum (SAM).

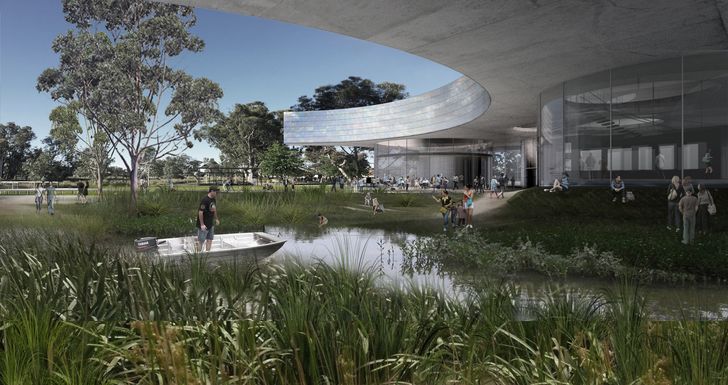

Shortlisted proposal for Shepparton Art Museum by Kerstin Thompson Architects.

Image: Kerstin Thompson Architects

The 2016 SAM competition called for an art museum in the Victorian regional town of Kanny-goopna/Shepparton, located on Yorta Yorta Country on the floodplain of the Goulburn River, at the edge of the city fabric in the mowed grass of Victoria Park. KTA’s approach to the brief, in collaboration with landscape architect Simon Ellis, was to invite the river in, making room for it and restoring a version of the riverside vegetation in place of the mown grass. The form and its siting came after this intention. The program would be elevated, creating a floodable undercroft that could be inhabited by an ephemeral river habitat. The elevated plan would be scalloped to allow sunlight to access the undercroft, creating a sort of anti-form where the requirements of the regeneration and system inform the eventual shape and plan logic. The building would address both civic and “natural” conditions in a moment of connection between the two through the section, where it would invite the river in underneath and connect to the urban context on the opposite side of the first floor, overlapping them. Whereas the town generally turns its back on the river, KTA’s design envisioned the ground plane as a public space, joining the civic and river fabrics. Here, the civic and ecological repair would be interdependent. In contrast, Denton Corker Marshall’s winning, built design for the museum, which opened in 2021, reinforced the mowed grass through the creation of an artificial hill on which the building was placed, separating it from the flooding (one hopes).

At Bundanon, a large property in southern New South Wales gifted to the nation by Arthur Boyd and his wife Yvonne,3 multiple new buildings by KTA (art museum, collection store and visitor facilities) extend concepts of ecosystem repair. The program is separated into smaller components that embed (the art museum buried in a reinstated hill for thermal stability and fire protection) or elevate (visitor facilities in the Bridge for Creative Learning).

Bundanon Art Museum by Kerstin Thompson Architects.

Image: Rory Gardiner

The land on which the Bundanon Trust properties are sited – more than 1,000 hectares abutting the Shoalhaven River – is undergoing large-scale ecosystem regeneration through the Living Landscape project.4 The theme of elevated buildings that release the ground plane is developed here in the literal bridge form of the visitors’ facilities (cafe, guest accommodation and protected undercover spaces). The 165-metre-long trestle bridge allows the ephemeral watercourse and “wet gully” landscape below, which was previously mowed, to function unimpeded. This landscape, which can be wet or dry, has been wet for most of 2022, supporting the newly planted indigenous plants.

In this project, Thompson worked closely with Nicole Thompson and the late Megan Wraight (Wraight and Associates), and ecologist, architect and landscape architect Craig Burton. Together, they mapped the dynamic plant communities in relation to the pastoral clearings as well as the phenomenon of the wet and dry gullies that brought forth the necessary entanglement of the site’s topography, hydrology and ecology. Wraight and Associates was part of the original core design team; its site analysis and preparation of the vegetation management plan underpinned early site-wide design intentions established with KTA, such as the circulation approach, a strategy of repair of endemic plant communities alongside the Boyds’ domestic exotic cottage garden. In time, and through the management oversight of Bundanon’s ecologist Michael Andrews, a rebalanced landscape will develop and form the setting that Thompson imagined.

Similar thinking around repair and renewal can be found in earlier work, such as House at Lake Connewarre (2002), on the land of the Wadawurrung People in Victoria.5 The site response – which situated the house at the edge of an escarpment, at the threshold between exotic and indigenous landscapes – was a collaborative one with landscape architects Fiona Harris and Tim Nicholas, and it is typical of KTA’s consistent cooperation with landscape architects, ecologists and others from whom the practice wants to learn. The project catalysed the client’s regeneration of the lake’s edge.

Today, the relationship between architecture and landscape is being dismantled and re-understood in ecological terms through an evolving lens of climate change and biodiversity loss. Architects are increasingly responding to the assertive voice of the landscape itself, such as the Goulburn River’s flooding of greater Shepparton in October 2022. Thompson is a pioneer on this front.

- Architecture Media, “The Architecture Symposium: A Broader Landscape,” curated by Kerstin Thompson and Phillip Arnold, 18–19 November 2022, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW; designspeaks.com.au/events/2022/11/18/the-architecture-symposium-sydney-2022.

- Kerstin Thompson, quoted in Leon van Schaik, Kerstin Thompson Architects: Encompassing People and Place (Port Melbourne: Thames and Hudson Australia, 2021), 51.

- The people of the Dharawal and Dhurga language groups are the Traditional Custodians of the land on which Bundanon sits. In Dharawal, the word bundanon means “deep valley.”

- See Landcare Australia, “Introduction to the Living Landscape Project,” bundanon.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/ 1-Introduction-to-the-Living-Landscape-Project.pdf.

- In the Wathawurrung language, Lake Connewarre is Kunawarr keelingk, meaning “black swan lake.”