REVIEWING THE GARDEN OF AUSTRALIAN DREAMS

The last case of a garden being censored was in 1620 in Heidelberg. There, the hortus palatinus designed by Salomon de Caus was erased by Catholic forces. Sadly, the historical record can now be updated to include contemporary Australia. Here, Dr John Carroll, a sociologist from La Trobe University is attempting to erase the Garden of Australian Dreams at our National Museum, and no one really knows why.

In responding to Carroll’s review of the National Museum of Australia and his subsequent comments in the media regarding the Garden of Australian Dreams, I (along with many others) expressed concern that the review exceeded its terms of reference and that the review panel were unqualified and ill-prepared to assess the museum’s landscape architecture.

As if this was not enough to invalidate the review’s naive recommendation that a team of scientists be consulted to make a “real garden” with sundials and fake rock art, I draw your attention to the following significant misrepresentation. Speaking on ABC Radio National (19/07/03 Comfort Zone) Carroll said:

“I mean the basic truth is that whatever the intellectual plan and intention for it, it doesn’t work. It’s not a garden, it’s by and large a concrete slab. It’s sort of unfriendly and I’m quoting, well we had over a hundred written submissions, we’ve interviewed forty or so individuals or groups of people and the sort of overwhelming consensus was basically it’s sterile, it’s unfriendly.

“… No part of the museum received such overwhelming and vehement criticism and hostility as the courtyard.” ›› Invoking “truth” and using strong language to make his point, Carroll effectively conjures an image of a horrible place that the public hate to such a degree that he had no choice but to propose its modification and ultimately its erasure. But, when you actually read all the written submissions to Carroll’s review, as I have now done, the garden is briefly mentioned in the negative only twice. In fact, the only criticism made by the submissions that can be said to be “overwhelming” is the criticism of the panel’s qualifications to conduct such a review. Additionally, we are told that the forty interviews Carroll refers to were largely conducted with those who made written submissions. Upon advice from one of his colleagues at La Trobe, Carroll rejected the museum’s own exit-polling which has surveyed more than 10,000 visitors, few of whom seem unhappy with the design.

One can only conclude that either some political puppeteer who really hates the museum’s design (and has nothing better to do) is pulling Carroll’s strings or Carroll is using a review process to express his personal predilection in matters aesthetic.

The latter is unprofessional, the former scandalous.

ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR RICHARD WELLER DIRECTOR, ROOM 4.1.3

I am writing to add my protest to that from others equally concerned with the unsolicited criticism and recommendations of the Museum Review Panel concerning the Garden of Australian Dreams. I am first of all concerned that a panel without critical credibility in the field of art should take upon itself the role of judgment on a major art work. My second concern is over the nature of the critique and the simple-minded, even gauche, nature of the proposals. These clearly demonstrate a complete misunderstanding of the project and a lack of any imaginative or creative ability on the part of the panellists. Third, I am concerned that it would appear that the pronouncements have been given credence in some places of influence.

I would suggest that if it is felt that it is desirable to evaluate the past two years’ performance of the Garden of Australian Dreams, that a suitably accredited panel be appointed to undertake this task.

JENNIFER TAYLOR ADJUNCT PROFESSOR OF ARCHITECTURE, QUEENSLAND UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY

ARCHITECTURAL CRITICISM

If Naomi Stead’s valuable article (Architecture Australia vol 92 no 6, Nov/Dec 2003) can be summarized as seeking answers to the possibly rhetorical question “Why does pithy quip prevail over detailed analysis?”, is not an inevitable answer in the current value system that “quick amusing always trumps long-winded boring”?

Many examples answer this question in the affirmative. Compare the impact of many newspaper political cartoons with that of editorials with exactly the same message.

However, if the point of Stead’s article is to advocate the reading and writing of literate dispassionate detailed analysis over merely skimming the comic section or looking at the pretties, then the continuing crisis Stead ultimately denies makes plain the real crisis actually asserted by her article.

As a lecturer in a university architecture school Stead cannot be unaware of the relative illiteracy of a vast number of students (and graduates), of the rampant prevalence of plagiarism seemingly tolerated, and of the preference for and attraction of minds, personalities, training and interests favouring passionate synthesis over dispassionate analysis among not only architectural students, but staff and the profession.

When will it end? When value systems change? With education? When necessary?

An example to illustrate comes from an issue raised with me yesterday when I was rostered as part of the RAIA counselling service which responds to calls from the public. According to a caller, as part of the vigorous and often overheated exchanges which regrettably seem to have become an unfortunate feature of development assessment in NSW, an RAIA member was alleged to have made disparaging remarks about the work of another professional unsubstantiated by any proper dispassionate analysis. According to the caller, there was much more “heat and light” than calm helpful analysis or discussion, and to his perception quite disproportionately scathing remarks were uttered. The caller, a professional man, sought to draw the attention of the RAIA members to what he, in his profession, might regard as not only unprofessional behaviour but possibly defamatory conduct.

So, as the crisis denied continues to manifest in many forms, the need for dispassionate professional detailed and accurate analysis must find new ways of expression if the message Stead’s article actually proclaims is to permeate further.Well done Stead for moving this ball along.Well done Architecture Australia for featuring it.

DR MAURICE EVANS

It takes courage to tackle the thorny subject of architectural criticism in this country.

Naomi Stead in her essay (Architecture Australia vol 92 no 6, Nov/Dec 2003) on the “three complaints” adopts an unnecessarily defensive stance by assuming that criticism requires a defence, when, in reality, it is the architects who continually attempt to subvert criticism and the editors who buckle under the pressure who should be in the dock.

The very fact that Stead feels a need to defend architectural criticism is symptomatic of the immaturity of the architectural community and especially the small circle of prominent architects who determine what goes. Paraphrasing D. H. Lawrence in Studies in Classic American Literature, the role of the critic is to save architecture from the architect who created it. Lawrence warned us never trust the architect. Trust the building.

Napoleon wrote accounts of his battles and sent them direct from the battlefield to be published in the Paris press. He clearly understood that power rested not in what you did but in how it was perceived, and he made certain that his voice prevailed and his failures were concealed. Such was his regard for the press. He dictated history.

Many of our big-name architects behave like Napoleon once did – hence the vital role of the critic in tearing aside the curtain of distortion. Where the professional stakes are high and reputations are involved there is no choice but to trust the one independent observer – the architectural critic. As Lawrence said, “Never trust the architect.” ›› The critic is like the war correspondent who sits in on military briefings only to hear the official military spin on what is happening, and then goes and observes the battle action.

Who would you believe: the correspondent with the front-line troops or the generals back at GHQ?

There is, and has been, a widespread failure of nerve in Australia regarding architectural criticism but this is not the fault of the critics; architecture magazine editors customarily refuse to publish contentious criticism that is likely to put them offside with an architect or is likely to affect future relations. The architects supply plans and photographs which they can withdraw at any time – that is, to blackmail the editor into giving a favourable review. They can also reject a critic suggested by the editor or refuse to cooperate.

Over thirty years of practice, I have experienced the entire gamut of intimidating and appalling behaviour dished out by our leading architects. The ultimate sanction is the threat of legal action. So frightened are editors that I once spent four hours with the legal counsel at The Australian newspaper in an unsuccessful attempt to publish an article on the subject of architectural criticism.

Whatever architects say, it is clear that few relish genuine criticism and, to varying degrees, they will manipulate and pressure editors and the critic to ensure only positive things are written about their work.

The result of all this pressure is to favour obsequious glib criticism that rarely probes deeply into ideas, history, appropriateness or the skill of the architect. Such compliant criticism in turn promotes a kind of immaturity, the sort you encounter in a kindergarten, criticism without sharp edges that might otherwise bruise such tender fragile old egos.

In an isolated society such as Australia’s, such architectural immaturity is allowed to perpetuate itself without undue comment or embarrassment, it persists, and is nowhere more in evidence than at National Awards night. Read the vigorous criticism published outside Australia, in the USA, the UK, in Europe, in, for God’s sake, that most polite of societies, Japan. In Japan, the editors commission the photography themselves, and thereby ensure complete control over what they publish.

As a co-convenor of a newly established Masters course in Architectural Writing and Criticism at the University of NSW, I have begun exploring such issues of power by explaining that criticism is not to be feared but is a tool to be used for analysing architecture and creating understanding and insight, that through a clearer understanding a design may be improved. Criticism rests on a base of literacy, its wings are history and theory, and its most valuable organ is a keen informed eye. Hopefully, students will learn that criticism is a process and is ideasdriven and fact-based, and is not simply a free kick at the work of another architect.

Good robust criticism goes hand-in-hand with excellence in architecture; without it, without genuine insight, the architect is literally in the dark.

PHILIP DREW ARCHITECTURAL HISTORIAN AND CRITIC

FIXES

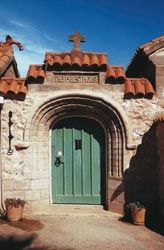

The Church of Our Lady of Mt Carmel, by John Taylor Architect, winner of the 2003 Lachlan Macquarie Award for Heritage. Photographs Claire Olsson.

The Church of Our Lady of Mt Carmel, by John Taylor Architect, winner of the 2003 Lachlan Macquarie Award for Heritage. Photographs Claire Olsson.

- We were incorrectly advised regarding the members of the RAIA National Awards jury.

Architecture Australia Nov/Dec 2003 (vol 92 no 6) listed Garry Forward as a juror. In fact, Jamieson Allom was the fifth member of the 2003 National Awards jury.