Value the teachers!

Dear Alec Tzannes,

“Those who can, do; those who can’t, teach” is a useless epigram. For – very often – those who can do cannot teach (in any field, not just architecture). And many of them, thankfully, have no ambition to do so.

Who is to do the teaching, then? You seem to be taking the line of the old saw in your editorial, “Changing Education Culture” (AA Jan/Feb 2008).

Our culture consistently fails to realize that teachers are as “born” as architects (and surgeons, authors, etc) are. There are people who can teach and those who can’t. And – again in every field – there are people who prefer to study than to practise (or to do both). In these people resides the knowledge that teachers draw upon to teach.

Practitioners who are in academe often are only able to proselytize, to expound their own method and style. Educators do more than this and thus they train the next generation to build on what has gone before.

Governments, and professional bodies like the RAIA, need to recognize that teachers are an invaluable resource and that they hold the keys to our future.

Donald Richardson

QUT RESPONDS

At QUT we are pleased to note the RAIA National Award for a small project at our Kelvin Grove Campus, but are somewhat taken aback by the criticism levelled at the client in the jury citation. As a discerning property owner and client, QUT over a long period has commissioned a number of young and emerging practices. We have never considered small projects to be in any way less deserving or to have less potential than that implicit in larger commissions.

We were surprised and disappointed to be described in the jury citation as an “apparently disengaged client”. It is unrealistic to expect the spatial and relationship context of every project to remain sacrosanct without also considering the pluralism of the broader campus community. For a dynamic city fringe campus undergoing extensive redevelopment, the realities of multiple demands for limited space cannot be ignored. In an environment such as ours, each project, large or small, exists in a delicate balance between context and survival.

It is possible that the Human Movement Pavilion may in fact have benefited from its adversity as much as it has allegedly suffered at the hands of an apparently disengaged client. In any case, enough merit has survived to procure an extensive array of awards and we join in congratulating the architects for their efforts. We are not convinced that the jury has fully appreciated the positive opportunities provided by the client, given the rather negative commentary.

Michael Green

Associate Director, Capital Works, QUT

Paul Morgan responds

I read with interest “The Critics Respond” in the awards issue (AA Nov/Dec 2007). The journal should be congratulated for encouraging dialogue rather than merely recording. I was particularly interested in Dr Sandra Kaji-O’Grady’s review of the awards outcomes (winners), “The Field”.

Sandra rightly praises Cassandra Complex’s animated The Smith Great Aussie Home. Of the three remaining projects, I will leave Brian Zulaikha and Donovan Hill to respond to her disappointment with the residential category. However, her critique of our practice’s Cape Schanck House is curious, almost as though a pre-existing set of biases towards contemporary residential architecture were applied without a close reading of the project. She states, “Today’s clients, even when the client and the architect are one … may be too concerned with property and resale values to step outside the dictates of ‘lifestyle’ and ‘market taste’ that leave us all hankering for excessive bathrooms … today’s houses conform to fashion.”

This is a little baffling. However, as an academic Dr Kaji-O’Grady will of course provide precedents for her rhetoric that the Cape Schanck house conforms to fashion. In the case of the Cape Schanck house, her precedents will be houses that utilize as a design strategy a sort of kinetics of the environment, synthesized with architecture as cinematic mise en scène (think of the way John Lautner’s houses have been used in film). Naturally she will present the fashionable precedents for the internal bulb tank that simultaneously cools the living area, provides harvested rainwater for toilet flushing and other uses, structurally supports the living room roof, plans the open area into discrete functions and symbolically locates water rather than fire or a plasma TV as the locus of the house. This little (135-square-metre) house does have two bathrooms, but then again it’s owned and used by two families.

What have we learnt from Dr Kaji-O’Grady’s paragraph on the residential awards? Certainly that fashion, or fashion design, is bad. Personally I’m a sucker for a 60s-style suit and a just-out-of-bed haircut. Following her line of argument, why then is the justifiably praised Cassandra Complex compared to a fashion designer, Vivienne Westwood? I think what she means is that in fashion design there are no new ideas, only old ones. Architecture, in contrast, emerges at dawn in a fecund, beautifully pure creative act (was that the distant resonance of Ayn Rand’s voice, or a trick of the wind?).

Any practitioner will tell you, it’s hard enough to get one decent idea up and going, let alone produce a totally original work. There’s always some sort of precedence. Let’s call it experience.

In reference to the Cape Schanck house, the section comes across as an exposition of pre-existing biases. Over to you, Sandra.

Paul Morgan

Brick baroque?

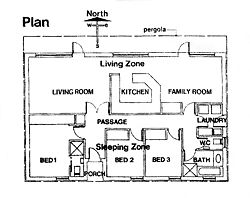

Thirty years ago, I was a director of the Brick Development Research Institute, a tenant in the Department of Architecture and Building at the University of Melbourne. Senior lecturer Alan Coldicutt arranged for graduate Sue Cumming to help me drive his then-novel thermal performance computer simulation program Tempal. We compared the performance of a well-orientated simple house in a variety of light and heavyweight forms of construction.

The house we studied is almost identical in plan to the one by The Rexroth Mannasmann Collective and Lucy Tibbits Architects, which received an Honourable Mention in the AA Prize for Unbuilt Work (AA Jan/Feb 2008). I suggest that substituting conventional full-brick construction with no wall insulation for the insulated sheet-metal-clad framed walls they chose would have created a substantially better performing house.

The paper that Sue Cumming and I produced, “The Low-energy Full-brick House”, was published in the Proceedings of the North American Masonry Conference, University of Colorado, in 1978. Its principal conclusion is that in Australia, hot summers cause more problems with energy consumption than do our comparatively mild winters, and that we are mistaken when we blindly follow the Northern Hemisphere by adding insulation to lightweight walls. The thermal inertia associated with uninsulated heavyweight walls is much more effective in controlling heat.

With good orientation, the uninsulated full-brick version on a concrete floor would be above 27oC for only 38 hours in a typical Melbourne summer period from November to March. By contrast, the insulated brick-veneer version on a timber floor would experience discomfort for 310 hours. The extra cost of full brick should be quickly recovered from the saving in airconditioning power, particularly with the predicted higher electricity tariffs. A full-brick house owner would then be well ahead, like the owner of a fuel-efficient car.

The “Agricultural Baroque” house might not appeal to its authors with brickwork as the external wall face, but its thermal performance would be hardly reduced were they to substitute metal-clad framed walls for the external leaf of brickwork – to construct in “reverse brick veneer”, with brick internal walls providing the thermal inertia associated with mass that is essential for good energy-saving performance in our climate.

Tom McNeilly