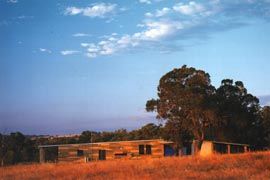

Looking across the Gingin Brook to the long north elevation of the Long Weekend House. Image: Robert Frith

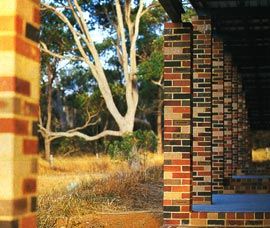

The brick colonnade, on the north side, was borrowed from a nearby sports centre. Image: Robert Frith

The brick patterning of the south facade indexes the manual processes of bricklaying. Image: Robert Frith

Looking from the living area into the kitchen/dining area and down the long circulation “corridor” on the north face. Tiered platforms provide a landing at the threshold of each room. Image: Robert Frith

View over the living area, with “King Gee Blue” highlights. Image: Robert Frith

The framed view into the study from the kitchen/dining area. Image: Robert Frith

The long stepped “corridor zone” is articulated through a linear succession of over-scaled doorways. Image: Robert Frith

The bathroom’s unexpected luxury. Image: Robert Frith

The “crude elegance” of the exposed steel beam.

The northern facade with its brick colonnade. Image: Robert Frith

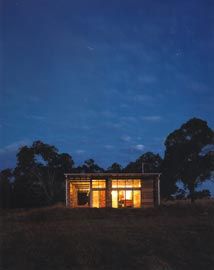

The evening view of the west facade demonstrates the layered organisation of the house, with colonnaded verandah, internal “corridor” circulation, and stacked living spaces. Image: Robert Frith

“This is not an easy house. It requires professional commitment and close visual attention, and is not for those architects who, lest they offend them, pluck out their eyes.

Indeed, its argument unfolds like a curtain slowly lifting from the eyes. Piece by piece, in close focus after focus, the whole emerges. And that whole is new - hard to see, hard to write about, graceless and inarticulate as only the new can be.” In a manner familiar to those who know the work of Simon Anderson, the Long Weekend House displays none of the identifying cues of “Architecture”. There are none of the luxurious materials or clever detailing of Wardle, nor the brute iconic minimalism of Marshall, nor the expensive “modesty” of a Murcutt farmhouse. This house is not stylish, flashily photogenic or controversial.

The Long Weekend House is difficult, rough, raw and intriguingly awkward. It refuses the glib, easy reading of the “beautiful” and the “figurative” and instead pursues an intelligent “ugliness”. Its formal idiosyncrasy, simplicity and economy, however, belie its architectural richness and a rigorous engagement with the local.

Located a hot hour-and-a-half’s drive from Perth, Gingin is a small country town that marks a shift in the landscape from the Swan Valley to the wheatbelt which stretches out across the Dandaragan Plateau. Gingin, itself, is located in a small green gully sitting astride a nondescript creek. In summer, the watercourse provides a green belt that distinguishes the town from the dun expanse that surrounds it. It is on the southern, frayed edge of the town, behind the sports centre and the railway line and just past the pub, that Simon Anderson and Kate Hislop have built their house.

Sited on a scrubby rise, the very long elevation of the house faces the approach road. A nascent landscape of native species planted in coloured belts - a piece of antipodean Burle Marx - falls away from the house to the north. An Aalto-esque series of terraces is intended to dissolve into the natural form of the site. The dwelling is a large but simple colonnaded volume contained by brick, tin and glass.

A straightforward constructional logic has been pursued; a double bay of brick columns step down the long axis of the house, the slab broken to clarify the fall of the site. The ridge line is located above the peak of the hill and the thin roof plane follows this descent. The resulting form echoes the familiar rural vernacular of long low sheds glimpsed on the journey through the Swan Valley, while the brick colonnade shading the north side of the house was borrowed from the nearby sports centre. The low spreading roof and long linearity of the plan also recall the Shingle Style work of McKim Mead and White and others. The resultant long section is improbably elegant for such a deliberately inelegant house.

For its modest program, the “bigness” of the house is surprising. The internal spaces describe a transition from the intimately scaled bedroom through to the expansive, open living areas. A sprawling study accommodates a workbench that wraps around all three walls. The kitchen/dining zone occurs in a spacious multi-purpose room with carefully framed views back into the study and out to the landscape beyond. To facilitate the generous expansion of the living area, a pair of columns has been removed and an exposed steel beam inserted into the span. Its structural efficiency has a crude elegance.

The clear legibility of the patterned brick structure and the lightweight infill means that the Long Weekend House could be read as part of the ad hoc vernacular tradition of the “sleepout” - where a verandah is enclosed to make a new room. In this variation the entire house is able to be accommodated in an over-scaled, disengaged verandah with only the heavy south wall remaining as the vestigial remainder of a mythical and now redundant house.

Mirroring the linear verandah space outside, circulation occurs along the glazed north wall in a manner that allows the “corridor zone” to be absorbed into the spaciousness of each room. The sense of “corridor”, in this instance, is created only by the linear succession of over-scaled doorways which deliver the occupant into the descending series of discrete spaces. An arrangement of tiered brick platforms, providing a landing at each threshold, makes for an unexpectedly formal transition between each room. The experience is at once grand and frugal.

In the tradition of “the ugly and the ordinary”, the house is finished in a selection of raw, utilitarian materials - daggy pine panelling, exposed jarrah beams, clear stained structural ply, rough whitewash and unglazed porcelain tiles. The bathroom interior, however, with its combination of ply, porcelain and white marble, is a moment of unexpected luxury. (The long distant views from the enormous tub toward the coast are spectacular.) A single tin of “King Gee Blue” paint provided the only applied colour within the house - daubed onto the dining table, the fibro cladding of the bathroom box and some miscellaneous cabinetry. The south elevation appears to be the most “figured” element in the house, apparently reminiscent of the decorative masonry experiments of Lyons’ recent work. Anderson and Hislop’s pattern, however, results from the manual process of bricklaying, rather than from any prescribed design. Remaindered (cheap) brick packs - rough clinkers, chocolate browns, flash fired silvers - were placed randomly along the south elevation, to be laid as required.

There is a certain pointed wilfulness in this rejection of the refined detail, the meaningful facade, and a sophisticated aesthetic. Yet, the Long Weekend House is self consciously architectural. It draws its inspiration from within the culture of architecture utilising both “high” and “low” sources. The rural vernacular, for example, is appropriated not for its romantic idealism but for its structural and economic efficiency. This is not about the conferring of a sense of “truth”, “honesty” or “simplicity” - notions typically evoked by the imagery of the rural shed. Instead, it is about building the most for the least in a manner contextually appropriate to the location.

With a kind of laconic integrity, this approach is what links the diverse selection of architectural images that Anderson and Hislop acknowledge as progenitors of the house.

Strong references to the utility and modesty of the work of an older generation of Perth architectural firms such as R. J. Ferguson & Associates, Cameron Chisholm & Nicol, and Forbes & Fitzhardinge imbue the Long Weekend House with its keen sense of the local.

In the seventies, these architects developed a regional architecture - a tempered Brutalism - of cream in situ concrete, timber and face brick for conservative institutional, corporate and residential clients. The Long Weekend House acknowledges the value of the experience and experimentation of these practices. By focussing on the local legacy as a point of architectural reference, Anderson and Hislop are able to rescue these obscure, unfashionable and threatened local histories from cultural relegation.

At the core of the work of Anderson and Hislop is a demonstrated commitment to the cultural richness of the architectural pursuit. The complexity of their projects represents a refusal to abandon architecture to the role of “lifestyle accessory” or to see it reduced to dumb scenography. There is a ruthless pragmatism apparent here which implicitly rejects the “perfumed bullshit” of much contemporary architectural discourse.

The calculated conservatism of the work of Anderson and Hislop stands as a strident rejection of the avant-garde and its relentless pursuit of “The New” in favour of a modesty that reveals a series of far more subtle critical manoeuvres. Its anti-aesthetic is quietly subversive - this is an architecture for the mind and of the memory rather than one that simply proffers a spectacle for the eye.

Philip Goldswain and Melinda Payne are graduate architects working for Ferguson Architects and is also co-editor of The Architect (WA). The introductory quote is offered with apologies to Vincent Scully, “Introduction”, Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture (The Museum Of Modern Art, 1977)

Credits

- Project

- Long Weekend House

- Architect

-

Simon Anderson and Kate Hislop

- Consultants

-

Builder

Simon Anderson and Kate Hislop

Engineer Structerre

- Site Details

-

Location

Gingin,

WA,

Australia

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Category Residential

Type New houses

Source

Archive

Published online: 1 Mar 2002

Words:

Melinda Payne,

Philip Goldswain

Issue

Architecture Australia, March 2002