Review Peter Kohane

Photography John Gollings

1 Standing side by side in Southbank – the MTC Theatre and the Melbourne Recital Centre.

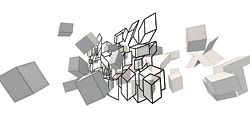

2 Diagram and animation stills exploring the three-dimensional geometric figures on the MTC Theatre facade, inspired in part by the paintings of American Abstract Expressionist Al Held.

3

4

5 3–5 Moving towards and around the MTC Theatre, the white pipes, disposed on a flat plane, give the impression of shifting and disintegrating three-dimensional forms.

6 At night the white painted steel pipes appear to be made of light, while the painted forms within the foyer add to the three-dimensional illusions.

7 Reflective surfaces create a vibrant ambience in the lower-level foyer.

8 The upper-level foyer. The geometric forms of the exterior pipework are translated into patterns on the internal walls.

9 The balcony enlivens the street during intermission.

10 The theatre, which can change colour dramatically through lighting, is lined with illuminated quotes from playwrights.

The MTC Theatre and Melbourne Recital Centre stand side by side in Southbank, the arts precinct for the city. While construction of the two buildings proceeded at the same time to an encompassing design by ARM, each has a distinctive character. I will consider the theatre first. Comments by ARM’s Howard Raggatt can then prompt an interpretation of the Melbourne Recital Centre, which involves the idea of architecture as a “cradle” for aspirations associated with music.

From Melbourne’s central grid, a person approaches the two institutions by crossing the Yarra River and passing along St Kilda Road, beside the front of the National Gallery of Victoria. He or she pauses at Southbank Boulevard. Looking down this street, with the side of the gallery on the right, one’s gaze is drawn to the MTC Theatre. Gleaming white painted steel pipes are visible. (At night they appear to be made of light.) Whether horizontal, vertical or diagonal, these striking forms are set proud of wall surfaces. In addition, the pipes can parallel the facades or jut out from them.

The beholder standing at the top of Southbank Boulevard is at a “sweet point” – here the pipes of the building, which in reality are on a flat vertical plane, add to the impression of clearly articulated volumes. The individual has entered the domain of artifice. ARM’s particular version of this is soon established: as the viewer moves towards the building, the stability of this three-dimensional arrangement disintegrates. Shifting and more complex networks of lines now confuse the eye.

In terms of the design process, the pipework on the MTC Theatre’s exterior conforms to ARM’s longstanding regard for the principle of imitation. The scheme drew on the interior’s main theatre, the metal frames backstage that function as scaffolds for performance sets. These technical supporting elements were absorbed within an artistic and playful act of architectural invention. This involved imitation of the internal mechanical forms, as well as paintings by Al Held, an American modern artist. Deploying bold lines in his late abstract works, Held stimulated the beholder’s alternating perceptions of three-dimensional geometric figures and two-dimensional patterns. This optical effect, which depends on the use of diagonals, contributed to ARM’s transformation of the orthogonal backstage forms into the more dynamic lines of the exterior’s pipes. The design was therefore enriched by the disparate sources of theatrical equipment and pictures by a fine artist. As a result, the prosaic task of assisting in the presentation of a play has been celebrated externally in aesthetic forms. The ornamental pipework intrigues the eye of the beholder and focuses his or her mind on the staging of a theatrical performance, where real situations are represented.

Through contrast, the theatre’s linear and often perplexing external ornament heightens one’s empathy with the Melbourne Recital Centre’s robust concrete forms. The more commanding demeanour of this building is appropriate. It is located on a prominent corner site, at the intersection of Southbank Boulevard and Sturt Street. The main front also responds to the interior’s main auditorium, the Elisabeth Murdoch Hall. Its relationship with the exterior, however, does not depend on interplay of forms, particularly of the kind considered germane to the MTC Theatre.

An understanding of the Melbourne Recital Centre must take into account its source of imitation: a white polystyrene packing device that, set within a cardboard box, cradles a precious consumer item, such as a computer. The polystyrene product’s distinctive formal attributes, which include rounded corners, protrusions and voids, are strictly based on function. Like a ship or automobile, admired by early-twentieth-century modern architects, the polystyrene object is perfectly engineered. For ARM, however, this logic and accompanying beauty cannot be disassociated from its redundancy. (The packing is discarded once the computer is removed.) Such esteem for what is not needed, described as “the affirmation of the negative”, informs ARM’s finest projects. In the 1990s, the firm studied St Paul’s Cathedral in London and St Peter’s in Rome. Each has an outer dome and, set within it, a smaller one. These forms were calibrated to impress a person in the city and the building’s interior. Yet the dim, left-over space between the two domes was prized by ARM, and emulated in the extraordinary volume for the stairs of the Storey Hall annexe. A related strategy was subsequently pursued for the National Museum of Australia. In this case, a knot’s solid presence was deemed less important than the space it would leave if extracted from a surrounding box-like setting. With this “not the knot” constructed as the museum’s grand entrance hall, space is animated by sweeping curves and convoluted rhythms.

The themes of the residual and disposable remained vital to the Melbourne Recital Centre. By imitating the polystyrene packing device, the building’s facade and foyer are richly configured entities. These take into account a beholder, who may feel an affinity with human-like forms, to also reflect on the significance of musical performances.

The influence of the polystyrene device on the main facade is evident in its whiteness and sculptural vigour. To create the latter effect, the architectural forms are hollow, their outer concrete surfaces carefully detailed and skilfully constructed. Such a craft-like achievement is especially evident in the bevelled edges, which highlight the thickness of forms, while suggesting that they are malleable.

The fulsome qualities of the Melbourne Recital Centre contribute to its anthropomorphism. When the polystyrene object was expanded to an architectural scale, the building assumed a hulking presence. Stocky legs appear as tapered piers, articulating the civic space of the street-level arcade, while shoulders are evident in the upper parts of the building’s two sides. In addition, the concrete structure embraces the large window, which nonetheless rises to create the pediment, a classical form associated with the head of a person or God. Ideal proportions are eschewed, so that one may readily empathize with lumbering forms. The building has a personality: it is ungainly, even a little unwieldy, but seems ready to trudge down the street.

When developing the design, ARM could turn the polystyrene object around and, by attending to its voids, generate the building’s foyers and other circulation areas. These are moulded and accord with the movement of human beings. From the ground floor entrances, people pass along stairs and platforms to the upper levels. The path, which is enlivened by views through the main window of the city, leads to the Elisabeth Murdoch Hall.

This interior is dedicated to a community of listeners and musicians, along with the art they cherish. The subtle but embracing curves of the two long walls, as well as their accompanying balconies with seats, assist in bringing people together. This is enhanced by the ornamental system, in which the grain of timber is expanded in scale, to determine the shapes of wooden panels. They are composed in layers and at varying scales. With patterns on different wall and roof planes repeated and contrasted, a unified effect is created. This addresses the eye and ear: the auditorium is a vessel filled with visual and musical harmonies.

Set deep within the building, the hall has no literal connection with the main facade and its source of the polystyrene object. Nonetheless, like the packing device, the Melbourne Recital Centre holds something precious.

When approaching the building at night, this could be encapsulated in the view through the window, where the illuminated foyers are brought to life by participants in a special event. Yet the same opening alludes to the Elisabeth Murdoch Hall. In this instance, the form of the self-contained room is subservient to the musical performances and accompanying cultural or spiritual aspirations. These are evoked in the facade, where the glass with its hexagonal frames rises like a flame through the entablature. Such a vital image includes the concrete forms, which act as a cradle.

Dr Peter Kohane is a senior lecturer in the Faculty of the Built Environment at the University of New South Wales.

11 The main stair to the upper-level foyer.

12 “The Ark is the object of a precious cargo, animals two-by-two.”

13 “White polystyrene is the cradle of the fragile, of the precious – a perfectly engineered embrace.”

14 Exploration of possible forms to cradle and contain the recital hall. 12–14 Concept images for the Melbourne Recital Centre.

15 View of the Melbourne Recital Centre from the corner of Southbank Boulevard and Sturt Street.

16 The western elevation, with a sign of the auditorium honed into the bluestone facade.

MELBOURNE RECITAL CENTRE AND MTC THEATRE PROJECT, MELBOURNE

Architect

Ashton Raggatt McDougall—project director Ian McDougall; design director Howard Raggatt; design architects Neil Masterton, Andrew Lilleyman; project architect Peter Bickle; senior project team Stephen Ashton, Paul Buckley, Jonathan Cowle, Stephen Davies, Doug Dickson, Jessica Jen, Ray Marshall, AnTony McPhee, Rhonda Mitchell, Will Pritchard, Simon Shiel, Ivan Turcinov, Andrea Wilson.

Project manager

Major Projects Victoria.

Contractor

Bovis Lend Lease.

Acoustic and theatre consultants

Arup comprising Arup Acoustics, Theatreplan LLP (theatre plan), Entertech/RTM International (theatre technology).

Building services

Umow Lai.

Structural and civil engineer

Bonacci Group.

Quantity surveyor

Rider Levett Bucknall.

Building surveyor

McKenzie Group Consulting.

Hydraulic engineer

Rimmington G and Associates.

Fire engineer

Thomas Nicholas.

Landscape architect

Rush\Wright Associates.

Accessibility

Morris Goding Accessibility Consulting.

Traffic engineer

GTA Consulting.

ESD consultant

Irwinconsult.

Planning

Urbis.

Signage and graphics

Vivid Communications.

Specialist lighting

Electrolight.

Facade engineer

Connell Wagner.

Client group

Melbourne Recital Centre—Arts Victoria and the Melbourne Recital Centre.

MTC Theatre—The University of Melbourne and the Melbourne Theatre Company.

The $128 million Melbourne Recital Centre and MTC Theatre complex was delivered by Major Projects Victoria on behalf of Arts Victoria and the University of Melbourne for the State Government of Victoria.

17 The moulded forms of the Melbourne Recital Centre entry foyer.

18 Entry to the stair from the ground-level foyer up to the Elisabeth Murdoch Hall.

19 The second-level foyer.

20 The grand stair to the upper-level foyer and Elisabeth Murdoch Hall is enlivened by views of the city and puts concert-goers on show.

21 The sculpted interior of the Elisabeth Murdoch Hall, the precious object cradled within the Recital Centre. Optimum acoustic conditions are achieved through the variable layered “grain”, out of which might coalesce images to amuse concert-goers with wandering eyes.

22 The smaller salon space, for pre-concert talks and experimental chamber music. The inscriptions over the canted wall panels are drawn from Percy Grainger’s Free Music scores.

23 Detail of the inscriptions.