REVIEW WILLIAM TAYLOR

Review

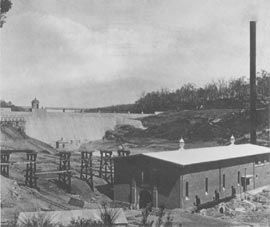

No 1 Pump Station, Munadring Weir, by George Temple-Poole, shortly after completion in 1903.

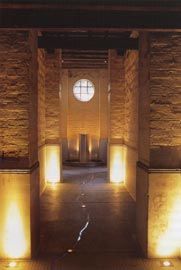

Stage 1 of the new musuem development, an installation in the entry passageway between the boiler room and the pump house tracing the path of the pipeline.

Stage 1 of the new musuem development, an installation in the entry passageway between the boiler room and the pump house tracing the path of the pipeline.

Stage 1 of the new musuem development, an installation in the entry passageway between the boiler room and the pump house tracing the path of the pipeline.

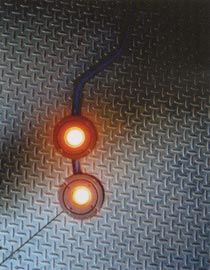

The proposed interpretative machine will occupy the volumetric space that formally housed the “C” pump. Image Exhibition services and Mulloway Studio.

The proposed interpretative machine will occupy the volumetric space that formally housed the “C” pump. Image Exhibition services and Mulloway Studio.

The proposed interpretative machine will occupy the volumetric space that formally housed the “C” pump. Image Exhibition services and Mulloway Studio.

ON 2 SEPTEMBER 1996, an event occurred at the weir at Mundaring in the hills above Perth that hasn’t happened since – the dam overflowed for the first time in fourteen years. It was an event noted by the press, having been anticipated following an unusually wet winter, and the dam site with its park-like setting was packed with scores of the curious, amateur photographers and relieved lawn reticulators. More recently, Mulloway Studio Architects have given the public another reason to visit Mundaring. In consultation with Paul Kloeden, Exhibition Services, Spellbound Interpretation of Melbourne and Scitech, the Adelaide-based designers have implemented the first stage of a plan commissioned by the National Trust of Australia to transform the pump station, museum and natural environs around the dam site into an interpretive centre explaining the history and significance of the Goldfields Water Scheme.

The installation of a new museum in the adjoining pump and boiler houses prefigures extensions to the existing structure itself, the construction of a visitor’s centre, educational facilities, tourist amenities, café and shop. These are designed to emphasize the visitor’s movement through the dam precinct in anticipation of a longer journey along the pipeline itself in an effort to encourage tourism in regional Western Australia.

Mundaring is the site of the first of eight steam-driven pump stations that form part of a vast technological apparatus. Planned in 1895 and fully operable by 1903, the station supplied the initial force to 23 million litres of water, carrying it each day through a network of reservoirs, storage tanks and steel pipes to the mining towns of Coolgardie and Kalgoorlie 560 kilometres away. The Goldfields scheme was by far the largest and most visionary of its kind undertaken in Australia until the construction of the Snowy Mountains Scheme half a century later. The pipeline linked not only Perth with Kalgoorlie, but connected the entire region with industrial and economic developments occurring worldwide at the time.

Ten years after its decommissioning in 1964, the No. 1 Pump Station at Mundaring became the C. Y. O’Connor Museum. Its exhibits told the story of the Goldfields scheme, commemorated the contribution of its chief engineer, and extolled the vision of then State Premier Sir John Forrest. On announcing the project, Forrest proclaimed that, “Future generations will bless us for our farseeing patriotism; and it will be said of us, as Isaiah said of old, ‘They made a way in the wilderness, and rivers in the desert’.” Since then, the pipeline has been much enlarged through local mythmaking and stories of derring-do.

In a move characteristic of our times, the current refurbishment of the pump station and its museum has produced a design that directs the visitor’s attention beyond a period of heroic engineering towards the broader context of Australian history, environmental awareness and human ecology. The O’Connor Museum celebrated the arrival of “rivers in the desert” with extensive and, by modern standards, overly crowded and humdrum displays. Its rebirth in the current work was initiated by the careful restoration of the building fabric designed by George Temple-Poole by National Trust architect Phil Bennett. Conservation work was carried out concurrently with the development of the new museum plan. Both aimed at producing a building that was legible and, significantly, one understood as a place of human labour.

In defining what this means, the design team was encouraged by the Trust, and its project manager Anne Brake, in their representation of the No. 1 Pump Station as an “artefact”. This is a familiar leitmotiv for architects, which is commonly expressed in restoration work. It coincides with attempts to respond meaningfully to the accretions that adhere to buildings over time – no less so sites of industrial archaeology. The redesign of the pump station interior was begun by clearing out the existing displays as efforts were made to present the machinery as free-standing objects within the large brick shell of the structure. Likewise, consideration was given to the various openings left in walls by the removal of fittings and to views outdoors, the intention being to emphasise the “foreign” character of the structure in the landscape. Inside, visitors are meant to occupy a space of enterprise emptied of the tangle of pipes and hissing valves, steam and sweat – the building becomes a lovingly restored, though ultimately thin, cover, like the cowling on an antique engine.

Unlike the engineers and stoke men of O’Connor’s era, today’s occupants are burdened with the labour of interpretation. Light and soundscapes replace the glow and roar of furnaces to create an introspective, almost church-like, space. Visitors are offered the difficult task of making sense of a story that is less easily understood through late nineteenth-century standards of patriotism and noble works of industry.

Rather, displays are meant to tell a multifaceted and incomplete story. Given the longterm impact of the scheme on native landscapes, one could reasonably question whether it should be commemorated at all. This is one possible conclusion drawn from displays in the boiler house where visitors are told of the vast timber resources consumed in the station’s furnaces and then offered a view of the partially regenerated landscape outside.

Of the three pumps originally occupying the pump house, only one remains and stands as a museum piece. Fortunately, the great expense required to make the equipment operational (and entertaining – an all too easy move for curators of industrial museums) has left its quiet dignity intact and required the designers to find other ways of capitalizing on our nostalgia for a time when machines actually did things rather than simply break. The foundations of the second and third pumps are incorporated into the installation in very specific ways and provide opportunities to use a range of interpretive techniques and multi-media. The absence of “B” pump creates “the void” over which visitors can reflect upon or call up for themselves, on computer terminals stories, historic photographs and oral histories and attempt to suggest the ghosts of people associated with the Goldfields scheme. The volume of space formally occupied by “C” pump is supplied with another, much larger interpretive installation or “machine” that details the history of the pipeline itself. These various techniques and media call to mind efforts aimed at encouraging an “interactive” experience in contemporary museums. These range from the National Holocaust Museum in Washington DC, which relies on biography to encourage a form of viewer-identification, to the Museum of Sydney with its cabinets of curious artefacts that invite the visitor to explore – in a sense, to invent – the past along with curators.

Between the boiler and pump houses, and forming the main entrance into the station, is a monumental corridor contained within existing masonry walls. An illuminated line is made in the raised metal floor reproducing the path of the pipeline and directing the viewer’s attention to an “altar” formed by a standpipe at the end of the corridor. This may remind one of that ubiquitous water feature of so many Perth suburban yards – the reticulation head severed by an aberrant land mower – though the designers intend a more literal reference to a now-iconic period photograph of Premier Forrest turning on the tap at Kalgoorlie.

Whatever vision Forrest might have had for the Goldfields Water Scheme, it was not intended simply to transform the desert into an oasis, but to water the mines and smelters that were – and remain – the economic engine of Western Australia. As each segment of the pipeline was completed and its capacity became apparent, thoughts on how to use this now-abundant resource for other purposes grew. Today, the authorities responsible for our water supplies no longer openly encourage its use as they once did in pipeline towns from Northam to Kalgoorlie, but rather its conservation.

It would be nice if the architecture of a museum alone could facilitate the kind of open-ended storytelling sought in the design of the No. 1 Pump Station. Here, considerable effort is given to present the complex reality of the Goldfields scheme and not to obscure it with “a romantic falsity.” But as Anthony Coupe and Paul Kloeden intimate, this is more than likely impossible. Desires for what any museum plan might call a “seamless interpretive experience” affords the integration of many, often irreconcilable programmatic requirements and the necessities of management, safety and especially, profitability. The viewer is inevitably “positioned” in some way as regards the interpretive displays. Still, this project is largely successful in fulfilling what most curators and their sponsors hope for these days: to encourage visitors to think as well as to be entertained.

DR WILLIAM TAYLOR IS A SENIOR LECTURER IN ARCHITECTURE AT THE UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA.

Project Credits

NO1 PUMP STATION, MUNDARING WEIR

Stage 1 Mulloway Studio, Paul Kloeden, Exhibition Services, Spellbound Interpretation, Scitech. Stage 2 Mulloway Studio, Paul Kloeden, Exhibition Services. Client National Trust of Australia (WA), Golden Pipeline.