Passionate, determined and debonair, Harry Seidler was one of Australia’s most significant architects for over half a century. He is remembered here by four friends and colleagues – Kenneth Frampton, Dirk Meinecke, Alex Popov and Peter Myers.

Photograph Eric Sierins

Rose Seidler House, Wahroonga. The first project designed by Harry Seidler in Australia, as photographed by Marcel Seidler, 1950.

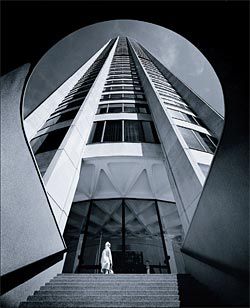

Max Dupain’s famous image of Seidler’s Australia Square, 1967.

Wohnpark Neue Donau housing estate, Vienna, 1998. Photograph Eric Sierins.

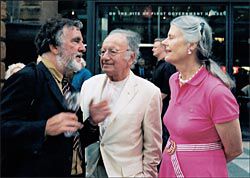

Harry Seidler outside the Museum of Sydney in 2005, (above) with Peter Myers and Penelope Seidler. Photographs Timothy Williams.

I first became aware of the work of Harry Seidler around the time that his first monograph was published. The book Harry Seidler 1955–63 became a point of reference for us in the basement office of Douglas Stephen and Partners in Wimpole Street, London. He appeared to us then as yet another distant hero of the postwar world prospering in the remote, beneficent climate of sunny Australia after the renowned achievement of his mother’s house.

Henceforth we would encounter his work from time to time in the pages of The Architectural Review. Little did I imagine then that I would meet him eventually some twenty years later in Sydney on the occasion of The City in Conflict conference given under the auspices of the RAIA in 1983. There he was, buoyant and bow-tied, the charming but belligerent Seidler championing the reconstruction of the Sydney Opera House auditorium and seeking our support for the cause.

It was a memorable moment for me because after the landing in Sydney I was taken to the top of some nondescript high-rise by a local newspaper and asked to comment on the Sydney skyline and to select what, in my view, were the finest high-rises in what was then still a rather small-scale city. Spontaneously my eye settled on three buildings, John Andrews’ American Express headquarters and Harry’s two mini-skyscrapers of the moment, his Australian Square and MLC Centre. There followed over the next day or two a soiree in the home of Harry and Penelope with all the international visitors in attendance and the illustrious Peter Myers, whom I met there for the first time.

These brief encounters were enough to cement our friendship, and three years later Harry commissioned me to write an essay for a monograph covering the first four decades of his practice. This I agreed to do, providing Philip Drew would also be asked to contribute a piece. It was necessary of course to have seen some of Harry’s more prominent pieces, and this I was able to do, but not to the extent I would have liked.

However, I did manage a trip to Canberra and hence a brief visit to the tectonically brilliant Trade Group Offices, completed in Canberra in 1974, which remains one of the most elegant, generic pieces of his mid-career, and which, incidentally, should surely be protected. Somewhat later I happened to be in Paris at that historic moment when Australia first captured the America’s Cup. I recall walking past the yin yang of the Australian Embassy, which, ablaze with lights and merriment, was a Seidler building in a festive mood.

Surely one of the most vital aspects of Harry’s civic architecture was the important expressive role played by structural engineering in the generation of his form.

This is very evident in such works as the Navy Weapons Workshop on Garden Island, Sydney, of 1985 and the Hong Kong Club in downtown Hong Kong, completed one year before with its 17-metre-span, column-free spaces. One might think of all of these works as amounting to a kind of isostatic baroque feeding partly off the joint legacy of Oscar Niemeyer and Marcel Breuer, with whom Seidler had briefly worked in the late 40s, and off the work of Pier Luigi Nervi.

Nervi was a perennial presence in Seidler’s architecture via his top assistant Mario Desideri, who was the engineer for many of Harry’s buildings from the mid-60s onwards.

One has to remark in passing that there was another side to Seidler’s output that one often tends to overlook, namely his feeling for collective habitation and residential space. This is evident at its best in his highly topographic Hillside Housing, Kooralbyn, Queensland of 1982 and in his city-in-miniature in Vienna completed in 1998 – the remarkable Wohnpark Neue Donau built over an eight-lane highway.

Over the years I would meet Harry and Penelope fairly regularly in New York, where they would regale me with stories of Seidler’s succès d’estime in Vienna. He quite justifiably perceived this as a kind of architectural homecoming, after an absence of virtually half a century, following his exile from Vienna when he was 15, following the Anschluss of 1938. Little space remains in this brief appreciation except to remark on his exceptional prowess as an architectural photographer, which was finally to be recognized with the publication of the book Grand Tour in 2003, designed by Massimo Vignelli and published by Taschen. I well recall trying in vain to get a New York publisher to take this on and failing dismally. Now, barely three years later, it has turned into a bestseller.

It has been translated into seven languages and gone through at least four printings of the original English text.

The last time I saw Harry was in 2004 in his office complex at Milson’s Point on the occasion of his 81st birthday. There he was with Penelope on the balcony of the mezzanine, looking down at myself and Richard Francis-Jones as we entered abruptly from the street. Glenn Murcutt and Wendy Lewin were there, on their way out presumably, pausing at our entrance on the stairway down – a set piece, as it were. We had inadvertently crashed into a meeting of the Australian Architecture Association.

The mood was festive; Harry was ebullient and beaming as only he knew how to beam, masking a latent shyness which was an integral part of his complex character. This is how I shall remember him: a debonair, cosmopolitan Australian-Viennese, a globe-trekker architect of consummate talent, ability and fulfilment, but still somehow an émigré who, after nearly sixty years, with all his honours on, had yet finally to arrive. KENNETH FRAMPTON IS WARE PROFESSOR OF ARCHITECTURE AT COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY.

A lot has been said and written, and will be said and written, about Harry Seidler the architect. I would like to shed some light on Harry Seidler the person. I had the good fortune to be around Harry for about a quarter of his life, and he was a caring, generous, passionate, modest and compassionate man.

Harry loved architecture but he had an even greater love for his wife Penelope.

Having convinced the parents of 19-year-old Penelope that he, at 35, was the right man for her, they enjoyed a loving partnership of some 47 years. They perfectly complemented each other, and in the office we rued the times when Penelope would travel on her own, leaving Harry behind in Sydney. He would arrive earlier than usual, be irritable all day long and then stay later than normal – all because he was missing his beloved “Penel”. In desperation I would ring up Polly to find out when her mother was returning, so we might know when peace and order would also return.

As a part-time first year student in Harry’s office, I asked him whether I might make use of his darkroom at home for my university projects. He agreed, and whenever I turned up on a weekend to toil away in the dark, he would knock on the door with an “Is it safe to come in?” to see what I was up to. Trading ideas, we would then inevitably retire to the balcony for a cup of coffee while waiting for the film to dry – it was hung on a paper clip in the breeze of the kitchen door. The talk, though wide reaching, always came back to architecture.

The sandwiches Harry offered on these occasions followed the simple recipe that he used each day at the office. Good, wholesome, heavy rye bread was consumed with slabs of cheese and cut-up capsicum, and accompanied by the ubiquitous kohlrabi. I am sure that many a visitor, invited by Harry to come and see him over lunch, arrived expecting somewhat more sophisticated fare, but Harry would not upset this routine for anyone.

The same modest tastes came to the fore when he visited me in Vienna while we did the Wohnpark Neue Donau housing estate.

He would delight in going to the Naschmarkt and picking up some fresh sauerkraut that the vendor would fish with his fingers out of a great timber barrel or in getting a simple bratwurst from a roadside stand. When we did go to a cafe or restaurant, he would happily relive childhood memories by ordering traditional hausmannskost meals.

During the first such visit, Harry insisted on staying with me in my tiny 26 square metre apartment for a fortnight. I had arranged to borrow a folding bed from bemused colleagues at the partner firm we worked with – on the assumption that I would be giving Harry my bed. They were alarmed to find that it was in fact Harry who was sleeping on the “banana lounge”.

He dutifully folded this up every morning so that we would have room to have our breakfast together before heading off to work. He delighted, as he did with so many things, in my way to work. Walking down to the Graben and down the Kohlmarkt, past the Loos House through the Hofburg, Harry told me I was the luckiest guy in the world and joked that I should pay him for the privilege.

I saw the same delight when we undertook tours through the Austrian countryside to scout out old castles, baroque monasteries and churches. Harry was always marvelling at and humbled by what he found around him. Memorably, he displayed the same sentiments in a cave in Kakadu National Park, declaring, “Now this is architecture. These guys knew what they were talking about. Leaves us for dead.”

Harry was intensely loyal to those around him. If anyone were in need of assistance, Harry would get on the telephone, write letters and do anything in his power to assist. When there were disagreements, he had the capacity to forget quickly and “get on it with” – he was not one to harbour bad feelings, always gave us another go and an opportunity to prove ourselves. In some ways we thought of ourselves as a ‘family” rather than an office in the traditional sense. DIRK MEINECKE HAS WORKED WITH HARRY SEIDLER SINCE JOINING THE FIRM AS A FIRST YEAR STUDENT IN 1984. HE ALSO SPENT THREE YEARS IN VIENNA, LIAISING WITH LOCAL AUTHORITIES AND CONSULTANTS FOR THE WOHNPARK NEUE DONAU PROJECT.

“There are no truths in architecture”, said Aalto, and whether or not you like Modernism, or Seidler’s interpretation of it, he has forced all architects to take their own position in respect of which architectural doctrine they will fight for and defend.

Harry certainly fought for his own position, which also became our shared legacy, in advancing an articulate and intelligent urban building response.

A lesser known quality of Harry Seidler’s, which is common to those who are at ease with themselves, is the generosity of time, information and support he extended not only to students and architects but to countless others who called on his wisdom and opinion. Harry always found time to talk and to support, or, when encouragement alone was enough, to clear the fog of day and maintain the fight to produce outstanding work.

Until Harry Seidler came along, Sydney had no debate about architecture and design. Harry empowered architecture to become a respected voice in the urban debate and elevated it in the public mind from a profession to a philosophical force to be reckoned with. We owe him a debt of gratitude for this, just as much as for the legacy of iconic buildings with which Harry Seidler has endowed Australia’s urban landscape. ALEX POPOV IS DIRECTOR OF ALEX POPOV ASSOCIATES.

I first encountered Harry Seidler in 1971 when I rented a shoebox in North Sydney in the same building as his office. This building, then something of a collectivist experiment, housed architects, landscape architects, graphic designers and photographers all working together (at least that was the premise). I scratched out a living on the first floor landing and Harry would occasionally drop by on his way upstairs (usually with some droll account of local scams being worked by persons from the other side of the Danube).

Harry, himself an entrant in the Sydney Opera House competition, was among the first to congratulate Jørn Utzon and his loyalty to Utzon never faltered. In early 1966 Harry organized an international petition in support of Utzon’s retention, the signatories of which included Kenzo Tange and Alvar Aalto. Notwithstanding, this appeal failed to move either the Askin government or the RAIA and Harry never forgave them: he even swore a statutory declaration describing the RAIA’s complicity in Utzon’s removal.

Yet despite his frontier bluffness, Harry was so intrinsically Viennese. Mention cafes and he elaborated the perfection of strudel at Landtmann on the Operngasse. Allude to Karlskirche and Harry would lovingly describe every last detail of Fischer von Erlach’s masterpiece. Appropriately, for Harry’s sixtieth birthday dinner, a cake was specially flown from Vienna; we each had a precious slice served on (of course) glass plates designed by Josef Hoffmann. Don’t worry, the accompanying (very good) white wine was Australian; it was Henschke!

Harry Seidler was a social democrat from middle-class Vienna. As an architect, Harry had no illusions as to how difficult it was to get something halfway decent built anywhere, let alone in Sydney. Though preceded by a number of gifted émigré architects, it was Harry who finally crashed through the stultifying conservatism of postwar Australian architecture and for this we will always be in his debt. Seidler’s first commission here, the 1948 house at Killara for his mother, Rose, is, fittingly, his finest building. Of course, Harry would vehemently disagree with this assessment of his work: as far as Harry Seidler was concerned, his best building was always his next. PETER MYERS IS AN ARCHITECT WHO HAS BEEN A SOLE PRACTITIONER SINCE 1970.