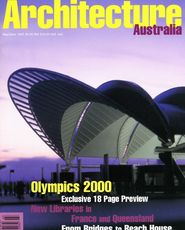

What will Sydney’s Olympics 2000 look like? Here are

recent perspectives on key precincts and buildings.

| SPORTS Olympic Stadium Railway Station Aquatic Centre Public Domain Athletics Centre Olympic Plaza Pylons Olympic Experience Centre Archery Hockey Centre Ferry Wharf | Update by James Weirick Sydney embarked upon the Olympics with supreme confidence-but behind the gloss there was no metropolitan strategy, no coherent masterplan for the Games facilities and no design vision. In the past year, a belated but heroic effort to make something of Homebush Bay has begun to turn around the masterplan and ‘design vision’ issues. The metropolitan strategy remains a serious worry. At Homebush, the Olympic Co-ordination Authority (OCA) has adopted a new approach to the 1995 masterplan (AA March/April 1996) and has implemented a potentially effective design review process. Design is now on the agenda in a big way-but beyond this site, the long-term problems posed by Sydney’s metropolitan structure seem as intractable as ever. For a city that has nowhere left to sprawl and a ring of inner suburbs cut up by flight paths and traffic arteries, the only way to accommodate metropolitan growth is to embark upon large-scale reconstruction of the middle ring suburbs. The Olympics could have provided the catalyst for this spatial, social transformation. Instead, the city is faced with the hurried implementation of bottom drawer plans from decades ago-a set of dubious proposals dominated by a north/south tollway aimed at directing as much traffic as possible through the centre of the city. The utter insanity of this proposition should be self-evident-but it is compounded by the fact that Sydney the Olympic City will be laid out east/west-along a landscape corridor extending from the ocean to the mountains. For an all-too-significant stretch, this turns out to be the nightmare alignment of Parramatta Road. Clearly Sydney should have had an Olympic plan linked to a transit-oriented future, and a form of urban governance capable of achieving this aim. Instead, responsibility for the city is divided among a bewildering array of elected and unelected authorities with no city-wide agenda, no capacity to act in concert and little in the way of accountability. The real problems of the city make the task of OCA look simple. As a single-purpose agency, it only has to design and construct the Olympic facilities-yet a year ago this task seemed beyond it in anything other than project management terms. To the great credit of the organisation, all this has changed. At last, design has been recognised as the key to achieving anything of value. This means having designers within the organisation, designers as key advisors and the courage to engage great designers as consultants. In many ways, landscape and public domain issues brought about this change. The 1995 masterplan, with its reliance on a grid of conventionally scaled streets and repetitive avenue plantings seemed straightforward. However, as major projects like the main stadium and the Royal Agricultural Society (RAS) Showgrounds were designed within this structure, it became clear that the public domain was not a neutral field or frame but a most significant experiential, sequential, symbolic container of space; with the capacity to unify, enrich and enliven the whole scheme. For its full potential to be realised, something more than simply assembling the landscape and streetscape components of each development package was necessary. In this context, NSW Government Architect Chris Johnson was engaged as the principal OCA consultant on the public domain, to orchestrate design quality via a new Government Architect’s Design Directorate (GADD) and Olympic Design Review Panel. Around the same time, Bridget Smyth was appointed OCA’s Urban Design Manager, to also focus on design quality. One of the first issues to test the suppositions of the 1995 masterplan was the configuration and detailed siting of the main stadium. The successful design by Bligh Lobb for AS2000 was significantly larger than the notional footprint indicated in the masterplan. This meant that one of the cross streets had to be eliminated-weakening the clarity of the grid and severing a potential link between the positive form of the stadium and the most extraordinary thing on the site: the negative void of the abandoned brickpit. As well, the detailed design of the showground raised the issue of its ‘permeability’-the extent to which the grid of streets within the RAS lease would be publicly accessible. This affected not only the quality and extent of the public domain but the capacity of the site to handle traffic flows at peak times. Another issue highlighted by the showground design was the impact of truck service zones and the long frontage of rarely-used animal pavilions on the human scale and liveliness of the Olympic Boulevard-and, indeed, two of the other main avenues. In the 1995 masterplan, these had been conceived to have some sort of ‘urban’ quality. When the RAS tried to be urban-for example, by attaching a contextual commercial block to the street frontage of its vast exhibition centre-the result turned out to be somewhat awkward, at least in formal terms. Viewed from the most heavily used pedestrian space-the entrance plaza to the railway station-the effect will be to supress an already suppressed dome. This may be an attempt to get into the funfair spirit by breaking a few design rules. However, the RAS deliberately chose not to use the ‘fun of the fair’ as the animating spirit of their new domain: they relegated the carnival rides and sideshows to the Olympic Plaza, outside their lease. GADD initially set out to address such issues by preparing a public domain strategy, area plans and design guidelines. However, it soon became clear that the most effective way to establish design principles was to do a design. At this point the experience of Atlanta was decisive, particularly in terms of crowd control, traffic movement and public amenity and enjoyment. A new conceptual overlay was needed on the 1995 masterplan. The designer engaged to do this was George Hargreaves, Chair of Landscape Architecture at Harvard ‘s Graduate School of Design and noted for his conception of public open space as a creative fusion of environmental art and environmental process. The Hargreaves/GADD team has brought great clarity to the masterplan through a series of quintessential moves. First, the key element of the 1995 masterplan, the Olympic Boulevard, was rethought from first principles. Although the boulevard had appeal as a civic gesture in the manner of Anzac Parade, it did not have a beginning or end and was loosely draped over a low ridge in a way that barely acknowledged the terrain. In the Hargreaves plan, the boulevard was revised to provide different experiences and conditions on each side of the hill: a tree-lined boulevard on the south side and a great urban plaza to the north. The crest of the hill was marked with a fountain and an evocative ‘Olympic’ grove; the far end of the plaza was signalled by another great fountain, designed to mist across the space using roofwater from nearby buildings recycled through an artificial wetland beside Haslam’s Creek. Here the environmental agenda of the Sydney Games has been given expression through environmental art-but more importantly, the urban plaza created an extraordinary space, scaled to the sculptural forms of the stadia, bounded by a forest of eucalypts and punctuated by lighting/signage towers. These have been designed with a ‘reconstructivist’ aesthetic, using steel recycled from the electricity pylons which once marched across the Homebush industrial wasteland. Across the plaza from the main stadium, a site formerly designated for development has now been dedicated as a park. Its development potential has been transferred to the commercial zone bounding the railway plaza. This new profile includes hotel towers with potential 360- degree views of the broad basin of the Parramatta River. Unlike the previous site, which was always intended to be retained as open space until after the Olympics, the new configuration allows the prime sites to be developed for Sydney’s prime time. The new park will save a significant stand of trees which will help provide a ‘forest edge’ of shade and coolness to the new Olympic Plaza. To give a modulated, human-scaled edge to the showground, Pavilion Architects have developed a steel colonnade incorporating hangar-style folding gates which can be closed to create a security fence at show time-but at other times remain open. The effect of Hargreaves’ changes to the masterplan has been to revive the concept of a sports park and notions of elemental space. This very much contrasts the previous ambition of an ‘urban core’-but the lack of a true urban program sadly doomed this approach. To recognise the new reality, the site has now been re-named ‘Olympic Park.’ To have created the ‘urban’ quality imagined in the 1995 masterplan would have required stadia in something like a square plan, incorporating cinemas, hotels and a shopping mall. Instead, we have single-use buildings proclaiming their individuality. Indeed, taken individually, the new hockey stadium by Ancher Mortlock & Woolley, the show ring by Cox/Peddle Thorp, the railway station by Hassell-even Bligh Lobb’s stadium-have strong sculptural qualities. They lack the effortless daring of Kenzo Tange’s Tokyo Gymnasium and, as an ensemble, cannot come close to the integrated vision of the Munich stadia by Frei Otto and Gunter Behnisch-but they are responding to the light and air of Sydney, the masts of the harbour, the industrial skyline of Rhodes and Camellia and, predictably, the potential of BHP steel. However, the small, peripheral structures suggest more potential to be memorable. As for the Olympic village: until the scheme is finalised we must reserve judgement. But the NSW government’s decision to drop the winners of the 1993 competition is deeply regretted. Four years later, we have another winning scheme-yet those four years should have been spent refining the original scheme or, if the Newington site was truly unmarketable, redesigning the village for Pyrmont/Ultimo. The fact is that Sydney needs a prototype to test ideas about urban reconstruction, transport and sustainability in the middle ring suburbs. That should have been one key legacy of the city’s Olympic moment-and without it, the Homebush achievement will ring very hollow. |