Geoffrey London argues that architecture matters more than ever in the broad provision of housing.

A special issue of The Architect—cover image of Subiaco City Hall by Hawkins and Sands; postwar houses below.

Much of my time as the Western Australian Government Architect is spent arguing why architecture matters. And most often it is to the measurable, pragmatic factors that I need to refer. While these factors are a necessary part of the argument, at times it seems like a deferral, an avoidance of the main game, a reductive strategy. And this is because there is not yet a broadly shared view in Australian society that architecture does matter.

In measurable terms, architects provide a service to society by designing buildings, and well-designed buildings can improve our performances. Agencies such as the Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment (CABE) in the UK are committed to quantifying the benefits of good design and are able to demonstrate some convincing results, as Shelley Penn reported in her recent AA article in this series, in health, educational, workplace and residential environments.

On the cultural and less quantifiable front, good architecture is a powerfully expressive medium which helps us make sense of where we are and what our values are, offers us sensory and intellectual experiences that no other art form can, heightens quality of life and challenges orthodoxies. These cultural values operate almost as articles of faith, as a belief system that is shared at least in part by our profession and by those who are receptive to the pleasures of architecture. But we haven’t been particularly successful in convincing a broader audience of these values.

Writing on “why architecture matters” is a challenge put to us in AA July/August 2006 by then RAIA President Carey Lyon to bring “the value of architecture to our culture … into the foreground of architectural discussion”.

A related question, but converted so that it becomes strategic, is “How can we make architecture matter?” One way of making architecture matter is to make it relevant to as many people as possible. Cultural buildings can do this, educational buildings can do this, health buildings can do this, but the broadest effect will be had in housing. Housing is a form of building experienced by everyone on a daily basis and therefore provides the opportunity to demonstrate most effectively the difference that architecture makes.

The time is right for some significant questioning of the housing we build. As lot sizes and households continue to shrink we build larger and larger houses, with the average area of the project house now in excess of 280 square metres. Shifts in the industry in terms of house size and diversity are discernible but slow in coming, and this is where architectural expertise could provide valuable guidance. As a profession we’ve done it before, as I outlined in “Architects and Mass Housing” (Architecture Australia vol 96 no 3, May/June 2007, based on a paper presented at the reHousing conference), through strategies like Boyd’s The Age Small Homes Service and the partnership between a number of very good architects around Australia with large volume project house builders.

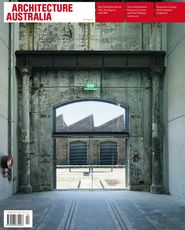

I recently revisited a special issue of The Architect, the RAIA WA Chapter journal. This issue was produced in April 1958 in association with the organizing committee for the eighth Australian Architectural Convention, held in Perth at that time. The intention of the publication was to record and celebrate the best of postwar Perth architecture, with the magical open staircase of the Subiaco City Hall by Hawkins and Sands on the cover. There are new high schools, a primary school, churches, hospitals and nurses’ quarters, numerous commercial buildings and, of the sixty buildings recorded, almost half are houses.

As was the case throughout Australia, constrained by availability of fi nance and materials, these postwar houses were not grand in scale nor conspicuous by concern for style. The largest of them seems modest by the standards of the project houses of today. But the architects extracted the most from these houses by exercising their design skills and generating rich ideas for contemporary ways of living. They provided site- and climate-responsive design, fl exibility in use, the considered capacity for expansion, free-fl owing but effi cient space, invention in material use and detailing, and a taut economy of form. This housing engaged the public and positively infl uenced the project housing that followed, with many architects all around Australia going on, over the next fi fteen to twenty years, to design for project house builders.

There is an opportunity now for the RAIA to take on an advocacy role across several fronts. In the first instance to its own membership, promoting a greater involvement in mass housing, and then presenting to the housing industry the benefi ts to be gained by working with architects. This advocacy could then be expanded to a brokering role, to bring architects and major builders of housing together to develop house designs that respond to current needs, all supported by demonstration projects, exhibitions and publications.

The RAIA could also examine the potential of developing policies to facilitate design quality in housing, such as the example of SEPP 65 in NSW, and then lobby governments on a coordinated basis.

I am convinced that housing – not the made-to-order house but the broad provision of housing in all its forms – is a great challenge facing architects in Australia and the means by which we may demonstrate to the broadest possible public that architecture really does matter.

Geoffrey London is Professor of Architecture at the University of Western Australia and the Western Australian Government Architect.

Graham Brawn on architecture in cultural change.

I have had the good fortune to travel, work and teach during very exciting times, and to be involved in effecting change and improving human environments through the processes of making architecture. I have also been heavily infl uenced by being part of dramatic events that came to be symbols of important periods of change.

I graduated in the early 1960s – an exciting time to live and practise in Sydney, working with Neville Gruzman, Bruce Rickard, Skidmore Owings and Merrill, and Laurie and Heath, and on commissions for family and friends. The 1950s and 1960s were explosive in the enthusiasm and impatience of young and old Australians to make good on social dreams and expanding wealth. Architecturally, Sydney was a veritable candy store of new offerings and responses to those times.

My wife and I entered Argentina for three weeks the night of the 1967 revolution. We arrived in Chicago for a stay of two years the week after the Democratic Convention riots of 1968. I was at work on the Saturday of the Minutemen rampage through Chicago, and we were in downtown Memphis the day after Martin Luther King’s assassination.

We found North America in the late 1960s and through the 1970s to be a place of intense social and cross-generational debate and disagreement, sometimes with violent confrontations, about values, ideas and lifestyles. The USA was grappling, socially and politically, with the need to remove its racist and segregation barriers and practices and to address the desperate condition of most inner-urban areas. Canada, after the 1967 World Expo in Montreal, seemed to leap out of the USA’s shadow and surge forward, proud and confident that it could become a genuine multicultural, bilingual nation. Both countries were affected heavily by the cross-generational conflicts over the Vietnam War and drugs.

America and Canada were in a period of enormous institutional change. There was eagerness in many quarters to think and act fairly, to operate in an efficacious manner, regardless of race, creed or social position. This was also the era of the growth of the graduate schools, which took people beyond the craft of their professions into scholarly practice, into new areas such as psychology and ecology and all their subsequent branches, and into thinking in terms of what we can achieve rather than limiting ourselves to what we have to do.

For architecture, this was a time of new types, such as social housing and the community college; enormous change in certain other types, such as the airport and the shopping centre; rapid expansion in general and attempts to change such venerable institutions as prisons. In urban planning and urban I design there seemed to be two concurrent fronts. The growth of suburb and of the expressway systems was threatening the fabric of the inner areas and consuming huge chunks of the arable land that had often been the reason for the original settlement. But there was also intense commitment to arresting the decay of the urban centres and to reinvigorating the inner suburbs.

Returning to Australia in 1980 to be an academic and, later, also a practitioner, I have been involved in similar intellectual debates and social, cultural and economic pressures for change. There is immense force for change in our corporate, learning and healing architecture, and for rethinking what we are about and how we want to live and support our fellow people.

Throughout this journey I have been driven by the search for meaning in architecture, and of architecture. My undergraduate thesis was The Social and Biological Needs of a Sydney Suburban Dweller; my master’s thesis was The Concept of Personal Identity as Determinants of Urban Physical Form.

This research, along with teaching and professional work, has convinced me that architecture is important in the following ways: • Good architecture gives shape, form, structure and expression to an idea about a better future. For example, the “architects” of the American Constitution designed a particular version of a democratic society and the ways it should function. The “architecture” of a computer determines exactly how it will operate. • As attributed to Robert Venturi, good architecture requires two ideas, and if the client doesn’t have one, the architect needs to have two, one of what is to be achieved and the other of how to do it. • Good design of anything takes us from where we are to where we want to be. • Design is also a verb. The making of architecture moves the art in architecture to being a lived art, in which an empathy for people and the things they do provides the basis for rooting the architectural outcomes in the circumstances and peculiarities of the situation, adding meaning and significance to those who use and experience it. • Design is about framing the problem as much as it is about problem solving.

In the midst of so much change in the way we see ourselves, and in how we want to live our lives, architecture is essential. Architecture as a finished object is more than a significant cultural artefact. Through its making, architecture becomes the means for individuals, organizations and communities to define and create the futures they desire.

Graham Brawn has been professor of architecture at the University of Melbourne since 1980. At the end of 2007 he retires to read, research, write and practise architecture.