<b>REVIEW</b> Philip Thalis

<b>PHOTOGRAPHY</b> Brett Boardman

A serious work of public infrastructure, this interchange, by Hassell with artwork by McGregor Westlake Architecture, celebrates the rituals of commuting.

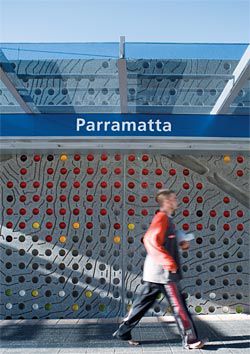

Movement Through Landscape, a public artwork by McGregor Westlake Architecture, mediates between the elevated station and the surrounding streets. The coloured baked enamel cups symbolize the movement of people through the station.

Looking along the Argyle Street elevation with the refurbished 1859 station building in the foreground.

The main entrance at Argyle Street. The glass louvred facade is designed to allow the penetration of natural light, natural ventilation and passive surveillance.

The western concourse with main entrance stairs and escalators seen on the left. This level links the underground with the newly completed Westfield Shopping Centre. There is also a planned Darcy Street Argyle Street 1 2 0 5 10 Underground link with Westfield Darcy Street Argyle Street bus interchange Station staff facilities Platform 1 Platforms 2 and 3 Platform 4 Roof level Platform level Western concourse level Argyle Street colonnade link to the proposed Civic Place redevelopment north of the station.

Looking along the colonnade at the main entrance, with the Argyle Street bus interchange to the right.

The main entrance to the station showing vertical circulation down to the enlarged western concourse.

The importance of infrastructure, particularly public transport, in structuring the city over time is not adequately appreciated in Australia. The Sydney to Parramatta rail line is a case in point.

The first section was opened in 1855, making it the oldest passenger rail line in Australia. This line and its successors, constructed over the period 1880 to 1930, remain the backbone of metropolitan Sydney.

Contrast this legacy with the folly of subsequent postwar planning which, based on car dominance and sprawl, missed the value of such long-term investment. Consider the nonsense of releasing a new Metropolitan Plan for Sydney with no transport proposals, which instead negligently relies on the rail infrastructure constructed by past generations – generations who demonstrably had a more acute understanding of city building.

These issues are particularly relevant to the new Parramatta Transport Interchange. As realized, it is but a fragment of the ambitious project originally announced. The crucial rail link from Parramatta to Epping was deleted, so the project brief changed to remove the proposed underground station, leaving the renewal of above ground station and interchange only, albeit with a budget of $200m.

Infrastructures are underlying systems that operate at the scale of the territory, the metropolis or the region. Traditionally, they have been the domain of engineers. In recent times, the architecture of infrastructure – that point of articulation where the system meets the people and the city – has grown in importance. Architecture has the opportunity to introduce character and identity, to provide connection and urban presence.

Parramatta Station displays one-and-a-half centuries of accretions, including the oldest remaining railway building in Australia. The City of Parramatta has recently benefited from renewed government attentions, planning initiatives and, most importantly, investment in public projects such as the new Police and Sydney Water headquarters, the Justice Precinct and Civic Place.

As the fifth biggest station in the Sydney network, Parramatta is neither a typical suburban station, nor quite a major city terminus such as Melbourne’s Southern Cross Station. The challenge here was to match the scale of the architectural intervention to Parramatta’s evolving urbanity.

Earlier masterplans for an interchange and enlarged station had been put forward by David Chesterman, of JTCW, and the NSW Government Architect. In the absence of a specialist transport implementation body (no surprise given the scarcity of such initiatives over recent decades), the NSW Government established the Transport Infrastructure Development Corporation (TIDC), formerly the Parramatta Rail Link Company, to act as the client and deliver the project. After earlier aborted international and local design competitions, the project was awarded to the Sydney office of Hassell, the team led by Ross de la Motte.

Hassell was not a surprising choice for the commission, as they have become the dominant transport architects in Sydney. Over the last decade, the practice has designed the grand station hall at Sydney Olympic Park, the Parramatta to Liverpool busway stations, the four new underground stations on the truncated part of the line between Chatswood and Epping, and now the New Metro Line in Perth.

The Parramatta project is extremely clear in its strategy and embodied understanding of transport operations. The architects sought to make this logic into the fabric of their scheme. The three main elements are as follows.

The western concourse, formerly a dark, brick trench, was doubled in width and volume to create a broad public connection between the northern and southern parts of the city centre. The platforms were extended up to 40 metres to the west to partially correct the curve of the existing platforms, and to better spread the peak crowd. The concourse organizes the space, orientation and functioning. It is generously top lit and open to the streets at each end, while escalators, stairs and lifts connect to the platforms above.

The steel canopy structures, which in section over-sail the entire station and engage Argyle Street, integrate structure, roof, catenaries, lights and services, drainage, and frame linear skylights. They have a rectilinear geometry in counterpoint to the curve of the platforms. The ceiling plays an acoustic role to quieten the noise of the trains. The canopies relate to the assortment of heritage buildings and structures retained on the platforms. To the streets are louvred, glazed walls and bus canopies.

External to the station but central to the transport planning, Argyle Street to the south was rebuilt as a dedicated bus interchange. In form and spirit it is the opposite of the segregated bus interchanges of recent decades, such as Edgecliff or Blacktown, non-places seemingly conceived to discourage public transport use. Here the street has been extended to the east under the rail line. However, the street required regrading to meet disabled access requirements, which necessitated placing the original station entrance building on a new plinth.

While the architects argued successfully for the street-based model, the transport planners mutated it into an exclusionary zone. This severs the physical and visual connections to the streets to the south, making the place sterile and potentially unsafe outside peak periods. This unfortunate arrangement could be partially rectified by adopting current European practices of flexible transit management, allowing “normal” street operations outside peak periods. This problem may be replicated on the north side of the station, with a proposal to narrow or remove Darcy Street, which gives access and address to the station. This is another case of self-professed transport planners, constricted specialists, undermining the fabric of the city, the openness of public space.

The exterior expression of the station, however, is greatly assisted by the integrated art walls. At Hassell’s instigation, McGregor Westlake Architects were engaged as artists for the embankment works that reconcile the elevated station with the bounding streets. With a background in art before becoming an architect, Peter McGregor has undertaken many art projects in the public domain. The perimeter walls are constructed of tall precast concrete panels, embossed with the curving alignment of the rail line and contours of central Parramatta, and inlaid with a grid of vibrantly coloured ceramic disks.

McGregor’s walls, over 150 metres in length, add a distinctive unifying presence for the station.

Hassell’s project reveals the tensions of public projects and pressures of making the city. Architects continually have to fight for architecture. In this instance they were aided by a project-specific design review panel of Alec Tzannes, Chris Johnson and Kim Crestani. It seems that public clients often have to be persuaded to act in the broader public interest, for the longer term public benefit.

The project bears some scars of “value engineering” and other determinist decisions that erode the architecture and its place in the city. While the diagram is strong, the architectural character is less memorable. The material palette is somewhat bland, while the roof and glazed walls lack the refinement (and budget) of the Sydney Olympic Park station. The project remains only partially realised, as the eastern ends of the platforms have barely been touched, leaving in place the daggy paraphernalia of older prosaic upgrades. One senses all around the battlegrounds of practice that Timothy Hill referred to in his article in a recent Architecture Australia (vol 95 no 6 Oct/Nov 2006).

Faced with such insistent pragmatism, architecture has no way forward if not founded on clear strategy, if not argued as an efficient response to functional criteria, if not robust in conception and construction. In such circumstances, wilful aestheticization has no way in. Hassell has sought to transform the data into architecture, to transcend quantities with qualities.

Walking about, awaiting the train or errant bus, the citizen can thank the Hassell McGregor team for adding a serious contemporary work of urban architecture to 150 years of railway infrastructure.

The work accepts and celebrates the daily rituals of commuting, the collective anonymity that typifies the metropolitan experience. Whereas the Parisians quip – “Metro boulot, Metro dodo” (Metro work, Metro sleep), Hassell has tenaciously attempted to civilize, if only for a few minutes, the grind of everyday life. This pivotal piece of public infrastructure receives and orients the bustling crowd, who are accorded by the architecture a touch of grandeur, a captured slice of the sky.

PHILIP THALIS IS PRINCIPAL OF HILL THALIS ARCHITECTURE + URBAN PROJECTS. HE LECTURES AT VARIOUS ARCHITECTURE SCHOOLS IN SYDNEY. HIS PRACTICE HAS BEEN INVOLVED IN URBAN PROJECTS IN CENTRAL PARRAMATTA.

PARRAMATTA TRANSPORT INTERCHANGE, SYDNEY

Architect Hassell— project team Ross de la Motte, Nesa Marojevi, John de Manincor, Steven Fighera, Christian Wild, Chris Harrhy, Igor Kochovski, Kathy Kralj, Michael Luders, Justine Butler, Dua Cox, John Lynch, Mal Graham, Greg Burgon. Structural engineering, vertical transportation, environmental consultant, geotechnical consultant and safety and risk consultant Arup. Civil consultants Arup, Sinclair Knight Mertz. Mechanical engineering, electrical engineering, lighting and hydraulic engineering Lincolne Scott. Signage/way finding Emery Vincent Design, Hermes. Public art McGregor Westlake.

Technical advisor Maunsell. Surveyor Hard & Forester.

Quantity surveyor Davis Langdon Australia.

Access consultant Accessibility Solutions.

BCA consultant BSS.

Environmental wind analysis MEL Consultants.

Contamination/ hazardous materials consultant HLA. Fire engineer Stephen Grubits & Associates.

Facade consultant Arup, Connell Wagner.

Traffic consultants Arup, Parsons Brinckerhoff Australia.

Heritage consultant Godden Mackay Logan, Clive Lucas, Stapleton and Partners, Tropman & Tropman, Peter Phillips. Client Transport Infrastructure Development Corporation.