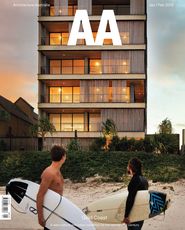

The highrise spine, clustered in all its thrusting assortment of heights and profiles, appears swathed in sea mist, gleaming in bright sun or electric in night-time spectacle as the predominant architectural form of the Gold Coast. This residential intensity, unique in Australia, stands in implicit dialogue with the sheer expanse of sand and then sea that is the defining geographical feature and historical raison d’être of the city. In this open space, individuals find themselves framed against the architectural stage and relish the solitude within nature before wandering back to the convenience of a hot shower and a flat screen.

In early 1959, when Architecture in Australia published its special issue on the Gold Coast, there were no highrises. The first – Kinkabool by Lund Hutton Newell Black and Paulsen – came later in the year. However, the issue clearly predicted both the potential and the dangers of a straggling extended strip city. This was more than a question of day-to-day planning and design. In nominating the most serious architectural challenge as “permanency beyond the existing temporal success,” the editors revealed the unease of finding relevance for the kind of solidity and serious intent offered by the profession. Such an ethic was incompatible with a place that revelled in an ambience of playful escapism and that was built on an underlying financial assumption of land speculation. This anxiety was justified when the celebrated Pfitzenmaier House by Hayes and Scott, with its dramatic butterfly roof, built as a weekender on the beachfront at Northcliffe in 1953, was demolished less than five years after it was built when the house changed hands and the land was deemed more economic as a multistorey site.

Image: John Gollings

In this recent suite of photographs, John Gollings brings a personal response to a place familiar to him since boyhood that nevertheless regularly surprises, intrigues and confounds. These images reveal a maturing city spine, remnants of domestic architectural flair and the settled permanence of impermanence that was so feared by the editors and writers of Architecture in Australia in 1959. Rather than the hero images of the latest in contemporary architectural design that Gollings is known for, this is a portrait of national and increasingly global economic conditions, of speculation and optimism, patience, decline and rejuvenation. Belonging to his wider interest in the documentation of the rise and fall of cities, collectively the images offer a reading of the resilience of the inherent changing character of the Gold Coast.

The Hi! House on the western side of Hedges Avenue, Mermaid Beach (aka the current millionaires’ row) was built in the early 1950s by a demobbed American major who married a local Brisbane girl. It encapsulates the shift in geopolitics that followed World War II, when Australia signed the ANZUS Treaty and looked across the Pacific for more than just military security. The synergy between politics and design is evident not only in the self-confident acclamation of the house’s name, but in the directional louvres, outdoor barbecue area and indoor-to-outdoor flow. On the corner directly opposite is another beach house, which was commissioned by a farming family from Gatton in the Lockyer Valley. Inside, both houses feature the informal open-plan layout that was once the preserve of the holiday house but has become an integral feature of the suburban Australian Dream.

Image: John Gollings

When Bruce Small took over Efim Zola’s ambitious new “Paradise City” canal development of the Isle of Capri in 1958, he brought all of the marketing skills that he had used to promote champion cyclist Hubert “Oppy” Opperman to the French in the 1920s and to sell Malvern Star bicycles to suburban Melbournites. Every bit of that promotional flair was required for purchasers to imagine their future on a freshly dredged island of sand and mangroves on a flood-prone river. But imagine they did and a two-storey house photographed by Gollings on Amalfi Drive, with a mature cypress, stands testament as an example of that willingness to embrace Small’s vision. Ironically, the key feature of the curved breezeblock wall is there to hide the prosaic necessity of the Hills hoist, a clever solution to the problem faced by architects designing for canal-side homes, which effectively have two fronts – water and street. On a dry block a few streets back, Gollings finds a rare virtual time capsule of a house, immaculate and modest, greeting the morning sun. It is probably little changed from the days when the adolescent Gollings drove around the suburb with his father, who was intrigued to see how Melbourne man Small was getting on in his new venture.

Not so lucky are two now equally rare examples of exuberant early 1960s homes that stand unloved, waiting to be part of some future consolidation. All the joyful decorative mid-century detail deployed in a two-storey home on First Avenue in Surfers Paradise – butterfly roof, exposed stone, filigree gate, raised brickwork and striped awning – cannot hide its abandoned state of disrepair. Just as tenuous is a more modest bungalow around the corner with a proudly Australian rendering of a kangaroo on the garage door. In contrast, cities as diverse as Palm Springs in California and Canberra have embraced and celebrated their mid-century architecture, but with a prevailing culture of the acceptance of impermanence, the Gold Coast appears determined to erase its own.

Image: John Gollings

Seeing a streetscape in terms of future potential becomes second nature on the Gold Coast. Just beyond a row of rudimentary fibro shacks, the three giant towers of the Jewel development, designed by DBI Design, are rising, evidence of the confidence of a new generation of international investment – this time from China. Those shacks wait their turn.

It was said that cranes are the surest barometers of economic confidence on the Gold Coast, but new indicators are there in unexpected places. Further down the strip, around Mermaid, Nobby’s and Palm Beach, an enterprising food revolution of locally run, casually sophisticated restaurants and bars, such as Poké Poké and Etsu Izakaya, inhabits the once untenanted shopfronts. Big development was hit hard during the global recession, but in the local tradition of small-scale, entrepreneurial risk-taking, new opportunities were found outside of the historic entertainment hubs of Surfers Paradise and Broadbeach. Signage that once had to be large and compelling enough to catch the eye of the motorist speeding down the Gold Coast Highway is now, through the pinpoint accuracy of social media and Google Maps, able to be discreetly cool. Doors slide open to reveal a lively, all-week crowd that continues to enjoy the Gold Coast in the way described in the 1959 editorial: “the tight alleys and dim restaurants, where nobody can be noticed but everybody can be seen.”

So what’s the way forward? An architecture coupled with entrepreneurship and expressive flair – nimble and responsive to the very human desire for spontaneity and joy that is so integral to Gold Coast character, sensitive to the subtropics and expressive of place – an architecture of serious play waiting to be made and then remade again.

The 2018 National Architecture Conference will be held on the Gold Coast from 6 to 8 June. For more information and to register, click here.

Source

Discussion

Published online: 25 May 2018

Words:

Virginia Rigney

Images:

John Gollings

Issue

Architecture Australia, January 2018