ONE BUILDING, TWO LIVES, TWO PRINTING PROCESSES. CHARLES RICE REVIEWS A RECENT EXHIBITION BY RICHARD GLOVER IN WHICH THE VARIOUS TECHNIQUES OF PHOTOGRAPHY CONFER SPECIFIC SENSES OF IDENTITY.

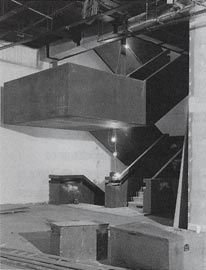

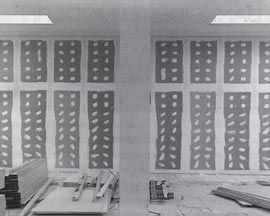

Silver gelatin print documenting the transformation of the shell of the Bankside Power Station into the Tate Modern.

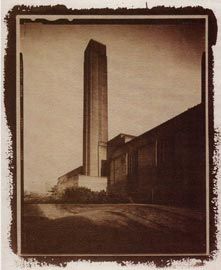

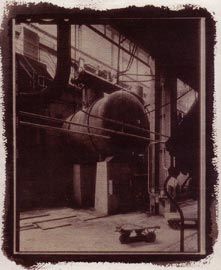

“Archaic” salted paper prints showing the intact but decomissioned power station.

“Archaic” salted paper prints showing the intact but decomissioned power station.

Silver gelatin prints showing the building during its transformation into the Tate Modern.

Silver gelatin prints showing the building during its transformation into the Tate Modern.

Silver gelatin prints showing the building during its transformation into the Tate Modern.

WHEN WE THINK of how photography would document the transformation of a built structure, we might imagine the way in which the camera would bear silent witness to this change, providing a record of slow transformation without any interference in this process itself. Yet Richard Glover’s photographs of the transformation of Giles Gilbert Scott’s Bankside Power Station into Herzog and De Meuron’s Tate Modern reveal how the various techniques involved with the photographic process can affect, if not a process of transformation itself, then the ways in which it can be interpreted visually. A selection of Glover’s photographs, taken over a period of seven years, have been assembled in an exhibition at the Point Light Gallery in Surry Hills, Sydney. The photographs are divided into two sets: those taken of the power station in its intact though decommissioned state, and those of the transformation of the shell of the power station into the gallery. This division is manifest through the use of two different printing techniques for the images: on the one hand, salted paper prints of the decommissioned station and, on the other, silver gelatin prints of the transformation into the gallery. This division in fact refuses a reading of the transformation as a continuous process.

Instead, it presents the radically different lives of the building: its “imaginary” past life as a power station, and the revealing of its new life as a gallery.

Apart from one overall view of the power station, the salted paper prints focus on its densely packed internal machinery. They reveal this machinery as an overdetermined mechanical labyrinth of pipes intersecting with junctions of valve wheels and dials. There is no “room” evident in these tightly packed compositions, and the power station itself appears to be bursting with these fittings of inconceivable function and complexity. This inconceivability is also carried in the distance the photographs posit between the viewer and the functioning of the power station. The printing process itself is positively archaic in photographic terms, and the qualities of the images that it produces become immediately associated with the archaic. The fibrous paper stock, and the way in which it softens the image, carries the affective experience of viewing the radical “pastness” of the building’s life as a power station.

The power station becomes a kind of imaginary object, severed from any reality as a working piece of infrastructure.

The silver gelatin prints, on the other hand, document in a very clear and sober fashion the construction processes involved with fitting out the spaces of Tate Modern. The selection of photographs shows mostly the processes of unveiling space from the scaffolding, both material and conceptual, required to bring these spaces into being. An image of drywall construction focuses our attention on the very banality of these construction processes, a sheer drabness that veils the scale of the shift from power station to art gallery.

These two series of photographs are separated in the hanging of the exhibition, but inevitably one’s interest is sustained in moving backwards and forwards between them. In viewing the exhibition in this way, I was gradually made aware of the gulf that separated them.

This is not a gulf that exists simply because two vastly different printing techniques have been used, but because these techniques heighten the distance between two vastly different buildings. There is in fact no sense given of the “slow transformation” of a single building.

None of the spaces between the two sets of images correspond. Indeed, the salted paper prints barely show “space” at all, and the silver gelatin prints seem to show only space. There is simply no evidence of how the clearing out of the power station machinery was effected. In short, there is no relation to be had between Giles Gilbert Scott and Herzog and de Meuron.

This is one of the strengths of the exhibition. It demonstrates how photography is able to confer specific senses of identity on built structures through the way in which the very techniques of photography are utilized and manipulated.

This being Glover’s strength, I was a little disappointed that the hang of the exhibition didn’t have the ambition to focus this strength. My own wanderings through the exhibition enabled this “non” relation between the two lives of the building to be made palpable, but I couldn’t help thinking that certain forceful juxtapositions could have been made by interleaving these two sets of photographs on the gallery walls. This gap between the “buildings” could then have been shown as the very force of the exhibition, as a critique of the idea that such a photographic exercise as Glover set himself could possibly have borne silent witness to all aspects of the building’s transformation. The camera cannot capture directly the moment when the imposition of a new order – not merely a new programme – is revealed in a building, but it can precisely and poignantly manifest the gap that appears because of this shift when the highly varied techniques of photographic printing are called upon and brought into new proximity.

DR CHARLES RICE IS A LECTURER IN ARCHITECTURE AT THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES.