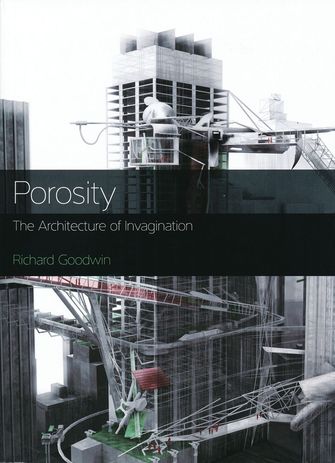

Porosity: The Architecture of Invagination by Richard Goodwin.

Richard Goodwin has dedicated over thirty years of research to speculating on the boundary between art and architecture and the complex relationship that exists between the two professions. He sees current urban architecture as failing humanity. Cities shape social and political bureaucracies as well as each and every individual, and with this in mind, Goodwin repeatedly states that we must accelerate change: we don’t have time for current architectural styles because they are redundant by the time they evolve. Goodwin sees public space as the oxygen of the city and in Porosity: the Architecture of Invagination (2011) he presents research on an architecture driven by interiority and its direct connection with external public spaces. Goodwin’s porosity paradigm thus views this spatial act, which he calls public art, as a very powerful mechanism for change in the city. Goodwin’s theories become something beyond architecture but something not quite urban planning.

His work is also beyond visionary. As Lebbeus Woods defines it, the term “visionary” generally refers to a person who exists somehow apart from the real world – as in “having visions.” Goodwin doesn’t believe he is practising speculative or visionary architecture. He states: “Some of us just can’t build what we want to but we are serious about what we theorize. I’m an artist architect – I like to make stuff, some of my parasites take six years to go through court. I’m not a paper architect.”

As an artist practising in London during the 1970s, Richard Goodwin began to explore his ideas through the rejection of the restrictions placed on him by the profession. Goodwin perceived the art spectrum as horizontal, with many professions along this line. This stance finds Goodwin in a constant whirlwind of curiosity, entering and exiting the world of architecture in an attempt to find the cure for his metaphorical itch. This constant search can partly be identified as the beginning of the search for balance within the virtual versus actual realm in which Goodwin has posed.

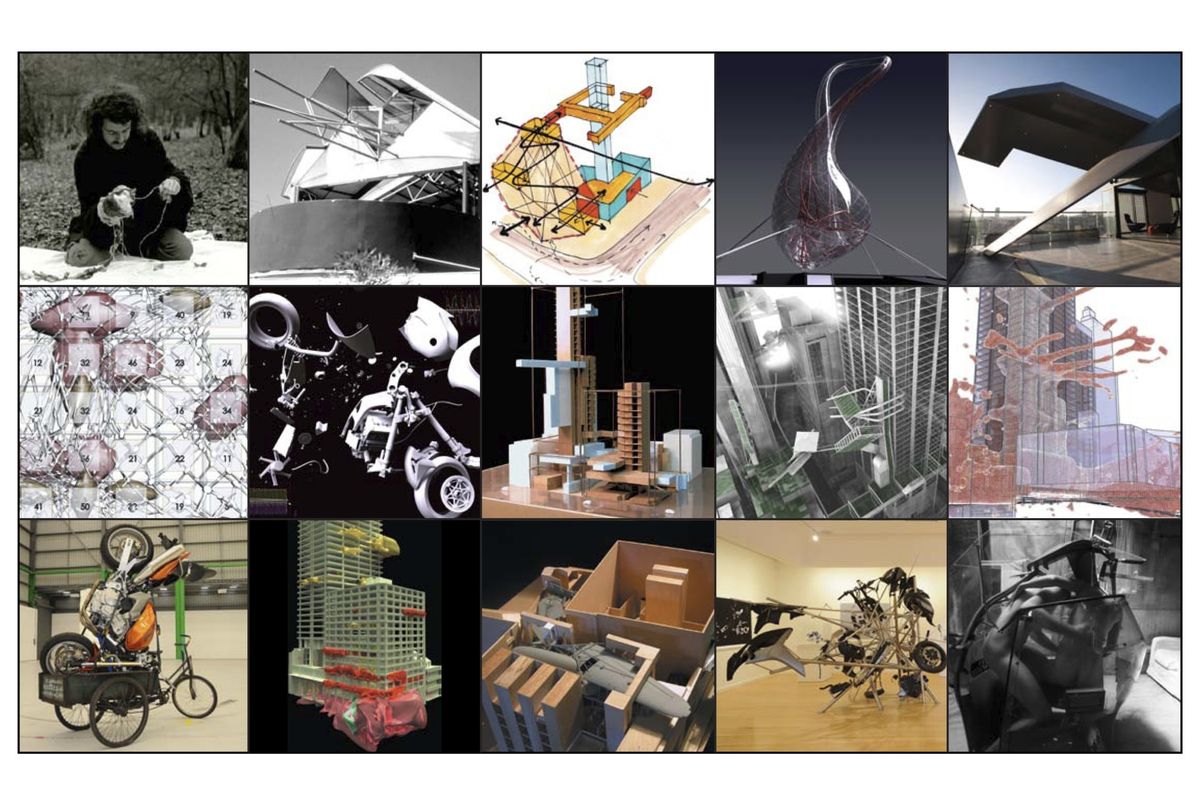

During his undergraduate studies, Goodwin’s practice started to manifest as performance art that provoked reaction to action and simulated human life and death. An iconic image for Goodwin was, and still is, Yves Klein’s performance Leap into the Void (1960), which demonstrates the power of the act (the leap) in comparison to the rendered vulnerability of architecture (the void). Goodwin’s Birth Ritual (1975), presented when the artist was twenty-two, was an unusual yet significant performance in his career. Using a rag doll twisted in cloth and an old acoustic guitar, Goodwin “gave birth” to his practice: the process of birth and the associated trauma represented Goodwin emancipating himself as an artist. To Goodwin, architecture, usually considered solid and perpetually strong, now became weak and plastic in comparison with the act represented via the performance. This idea is further illustrated in Porosity where Goodwin states that he is “interested in the immense fragility of architectural fabric in relation to the act of a single body.” This apparent paradox between architecture and performance art has allowed him to establish his ideas about porosity.

Lebbeus Woods identifies at least three essential attributes that all visionary architecture addresses; Goodwin’s Porosity explores them. Firstly, Goodwin’s porosity research proposes a new and radical conception for the vision of cities. Porosity, which he has defined as the permeable edge between public art and private space, deals with existing structures to create three-dimensional complex public systems. Secondly, the proposals are total: all scales, from the individual to the urban field, are addressed. Goodwin’s practice is tied back through the “scales of tools” that he uses to deploy his theories. Exoskeleton, the first in the scale of tools, is where Goodwin challenges the body with constructions using ready-made objects that trace the obscure point at which the body ends and architecture begins. The second tool, Parasite, operates at the scale of installation and the city. This is where architecture and public space is challenged with parasitic structures that cling onto existing buildings like leeches onto the skin; hence, questions around the facade or “skin” of architecture are raised. And the last tool, Porosity, is at the scale of the urban infrastructure. It is here where the boundaries between public and private space are blurred and redefined.

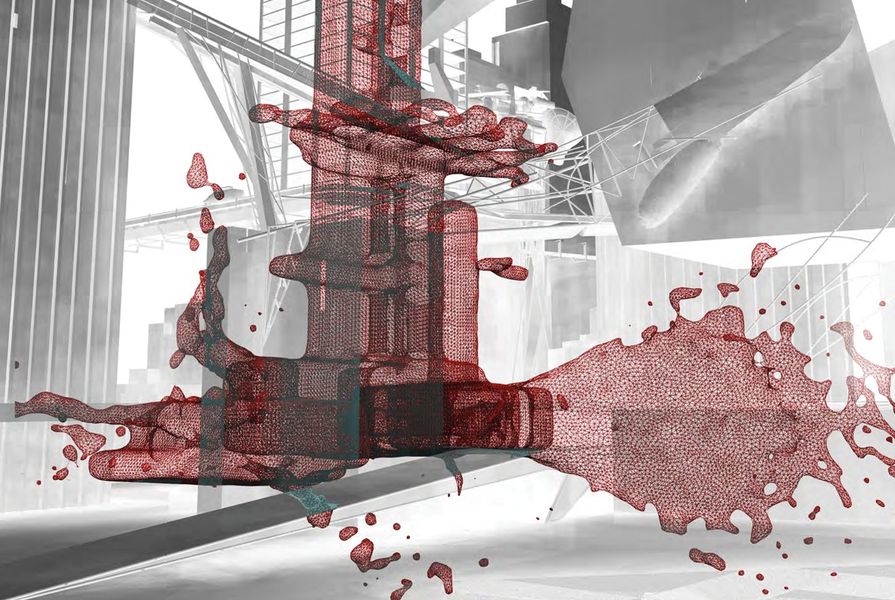

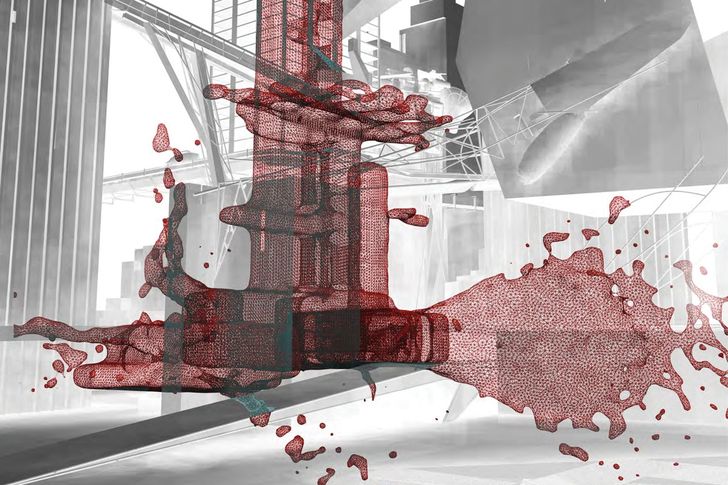

One of a series of provocative rendered images that explores the potential of connection from inside out and vice versa.

It is this third attribute that deals with singular interventions (the parasite) as the potential answer for the urban catastrophe that Goodwin speaks of that most illustrates the above-mentioned gap within visionary architecture. From a user’s perspective, Porosity becomes a tease within the urban space; a meandering trail through anything from moments of transition and connection to endless empty foyers, back streets, toilets or sewer pipes. Goodwin’s text sets out to prove the Porosity hypothesis, where the city becomes the laboratory for the testing of ideas and plays the possible role of catalyst. The Porosity project, conducted from 2003 to 2005, involved a series of experiments where a “porosity researcher” enters three unknown private sites including Zone 1: 345–363 George Street, Zone 2: World Square and Zone 3: Aurora Place, Governor Phillip and Macquarie towers, attempting to remain unnoticed for as long as possible.

The mappings and findings through what Goodwin calls the “chiastic spaces” were recorded and a “porosity index” was produced, which gave a figure for comparing the degree of the “publicness” of a building. With this index and a tri-part series of models/diagrams a series of provocative rendered images was produced that explores the potential of connection from inside out and vice versa. The problem with this conclusion is that the representation, through red explosions as renders symbolic of the new linkages, takes a fictional form. From a designer or critic’s perspective Goodwin may be considered to have put the reader at a distance that may only enable us to interpret the image with critical eyes. In that sense the porosity index and its mappings represent a provocation.

When questioned about these “red explosions” Goodwin states: “The explosions are simply unused spaces, at a time that have gathered together, they are brothers and sisters of public space; they represent a patch which might become something else.” Even though the porosity index is a clever and new way of analysing the publicness of a building, there still seems to be a step missing from these images and from the index itself to the stage of the parasite. When interviewed, Goodwin commented on this missing step and about how he tried to narrow the gap between the physical and performative through quantifiable metrics so one can do a fairly objective analysis. Evidently, there’s a gap between playing with that and the physicality of doing it, but in actuality it may be impossible to ever close that up – there’s a healthy oscillation going on between the mentioned virtual concepts and the physicality of the actual model within urbanism. It is vital, in this sense, that an understanding of this oscillation is embedded into the design process where the gap stands today. Goodwin provokes really good thinking about urbanism as a series of problems understood from first principles. Therefore, within architectural criticism these principles or virtual realities play as transitions, and through the questioning of one’s perception the actual, in time, will be revealed.

Richard Goodwin, RMIT University Press, 2011. 265 pp. RRP $49.98.

Source

Discussion

Published online: 16 May 2013

Words:

Endriana Audisho

Issue

Architecture Australia, January 2013