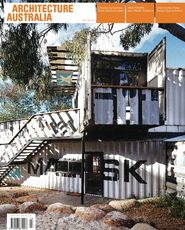

The elliptical form of 1 Bligh Street seen in the Sydney cityscape.

The external foyer and publicly accessible ground plane.

Oblique view of the highly transparent facade.

Detail of the double-glazed facade. The inner skin is sealed performance glass; the outer, ventilating skin is clear, low-iron glass. Operable blinds within the cavity provide solar protection.

An aluminium walkway between the skins allows air movement in the cavity.

Next-generation workspace. Philip Vivian discusses the refined proposal for Sydney’s 1 Bligh Street by Architectus and Ingenhoven Architekten.

In 2006 Dexus Property Group (formerly DB RREEF) sponsored a City of Sydney Design Excellence Competition for a high-rise building. The site is located on land they had amalgamated on Bent Street, between O’Connell and Bligh Streets, across the street from Denton Corker Marshall’s Governor Phillip and Governor Macquarie Towers. The entrants were Crone Partners, Johnson Pilton Walker, Hassell, Rice Daubney, and Architectus, who formed an association with Ingenhoven Architekten, the German firm led by Christoph Ingenhoven. The aim of the competition was, in the words of Dexus’s Head of Development and Building Services Tony Gulliver, “to create a next-generation workspace, one that would still be considered highly contemporary at the end of its first lease cycle. To achieve that, we tried to predict future tenant requirements and thus focused the design brief on indoor environmental quality and energy-efficiency, as well as workspace qualities such as access to natural ventilation, large floor plates and vertical and horizontal connectivity.”

In accordance with the City of Sydney planning process, a Stage 1 DA prepared by Architectus had already received approval for the envelope, massing, height and land use. The competition entrants generally created rectilinear towers with a stepped massing to comply with the approved Stage 1 DA envelope. Each design exhibited differences in core locations, atriums, podium treatment and tower skin. They were essentially variations on the Stage 1 DA planning controls, with varying degrees of competence and resolution.

One solution, however, was literally “out of the box”. The team of Architectus and Ingenhoven Architekten produced a highly refined elliptical scheme. It elegantly resolved, in a single move, the shift in the urban grid along Bent Street, the corner location and relationship to Farrer Place, harbour views, floor plate design and environmental issues. Indeed, the scheme synthesizes many of the German architect’s interests in integrated design, workplace planning and ecological building.

The design proposal is an ellipse in plan, rotated diagonally across the site so that it aligns with the street grid from Circular Quay and addresses the harbour. This masterstroke allows the tower to formally address Farrer Place and the alignment of the heritage buildings between Bridge and Bent Streets. Not coincidently, it also maximizes harbour views.

The core is located on the south, non-harbour side of the floor plate, creating a large, open, flexible floor plate looking to the harbour. This core has been split into two halves, framing a heart-shaped atrium rising the full height of the tower. Glass lifts activate the space, while the office floors step in and out to create opportunities for interaction with other tenancies. This atrium is literally and symbolically the communal “heart” of the building.

In contrast to the other entries, the scheme rises from its publicly open and accessible ground plane to its top without steps or setbacks. While not literally complying with the city’s setback requirements, the elliptical form satisfies the intent of eliminating long tower walls on the street boundary. The tower is split into a low-rise and a high-rise volume, with communal spaces integrated at its base, middle and top.

At the base the tower is raised above the street level, creating a north-facing publicly accessible ground plane and allowing the visual extension of Farrer Place into the site. The ground plane consists of a curved sweep of steps, accommodating the level changes and incorporating a child care centre in addition to the tower lobby/wintergarden. The sheerness of the tower is interrupted at the midpoint by a setback level with an outdoor terrace. This level, which is the transfer floor between the high-rise and low-rise lifts, is proposed as either a function and conference space or a specialized reception area for a head tenant. At the top of the building is an open landscaped roof terrace, surrounded by a ten-metre-high glass screen, extending the interest in roof terraces seen in Ingenhoven’s previous buildings and creating a dramatic, accessible roof space on the skyline of Sydney.

The facade consists of a double-glazed skin of full-height glass, with a sealed performance glass inner skin and a ventilating outer skin of clear, low-iron glass. The clarity of the glass will ensure a highly transparent building. Operable computer-controlled venetian blinds are located within the cavity, providing solar protection to the glass. This 600-mm cavity is ventilated on a floor-by-floor basis. An aluminium walkway at floor level between the layers allows air to enter the cavity at the base and to ventilate out at the window head. This is a variation on Ingenhoven’s patented “fish head” design developed for the RWE Tower in Essen.

The structural design, like the concept design, is clear and straightforward, with a few elegantly simple decisions that elevate the overall idea. The structural layout consists of a series of radiating beams that respond to the elliptical shape. Each beam has a 16-metre primary span, with a 5.3-metre cantilever, creating a column-free facade. A series of steel props at the slab edge provide stiffness to the cantilever to allow for curtain wall tolerances. This innovative structure was developed by ex-Arup-director Ross Clarke and his firm Enstruct.

Environmentally, the building is aiming for a six-Green-Star rating and a five-ABGR rating, the highest attainable standards. The major innovation is the double-skin facade, which provides thermal comfort and glare control while allowing floor-to-ceiling glazing to maximize the view. A hybrid tri-generation system uses gas-fired cogeneration, absorption chillers and solar energy to generate cooling, heating and electricity and reduce peak energy demand. Breakout spaces and the entry lobby use a relaxed set of comfort criteria to create a year-round tempered environment using recycled heat and relief air. In addition, the building uses a black water treatment plant to recycle waste water for use in flushing toilets and for cooling towers, and a rainwater tank for irrigation.

The design raises queries about the environmental performance of a double-glazed facade in Australian conditions and the potential success of an open undercroft. International architects have had success in convincing the City of Sydney of the design merits of this approach, yet with mixed results. The amount of solar penetration to the space will be crucial.

The Architectus and Ingenhoven proposal has recently received approval for a Stage 2 DA with the City of Sydney. It remains to be seen whether this superlative design can be realized in Australia to a standard equivalent to Ingenhoven’s work in Europe, or whether it will be compromised to the degree that has resulted in other internationally renowned architects refusing to turn up to the opening of their buildings, as occurred recently in Sydney. Much will depend on the resolve of Dexus and the selected builder.

Ingenhoven’s integrative design approach has created a single elliptical shape that responds to the city morphology and to the street grid shift at Bent Street, addresses Farrer Place, maximizes harbour views while minimizing the ratio of surface-area-to-volume, and creates an elegant volume at a pivotal location in the city. Dexus Property Group and the competition jurors are to be commended for the selection of such a comprehensive modernist scheme. If it can be realized, it will surely add an architectural landmark to Sydney’s skyline and establish a new benchmark in integrative, ecological workplace design in Australia.

Philip Vivian is a director of Bates Smart, Sydney.

1 BLIGH STREET, SYDNEY

Architect

Architectus and Ingenhoven Architekten—Architectus director Ray Brown Ingenhoven director Christoph Ingenhoven project architect Mark Curzon.

Client

DB RREEF.

Project manager

APP Corporation.

Structural consultant

Enstruct Group.

Acoustic, electrical, hydraulic, fire services, facade and mechanical consultant

Arup.

Facade engineer

DS-Plan.

ESD consultant

Cundall.

Hydraulic and fire services consultant

Steve Paul and Partners.

Landscape consultant

Sue Barnsley Design.

Lift consultant

Norman Disney Young.

Quantity surveyor

Rider Levett Bucknall.

Traffic consultant

Masson Wilson Twiney.

Building code consultant and certifier

Davis Langdon Australia.

Accessibility consultant

Morris-Goding.