We need creative and innovative architecture to inspire sustainability reform. But we also face new, more demanding, prescriptive mandatory energy efficiency requirements. With the increase in the mandatory BCA Section J provisions, Wes Mergard of EM

From May 1 this year, the Building Code of Australia (BCA) will significantly increase the stringency of the energy-efficiency requirements of Section J in an effort to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.1 During the proposal stage, modelling by the Australian Building Codes Board (ABCB) indicated that the changes between BCA 2009 and BCA 2010 would have the following outcomes:

- Offices – between 14 and 22% energy reduction

- Schools/universities – between 18 and 31% energy reduction

- Department stores – between 22 and 27% energy reduction

- Hospitals – between 14 and 40% energy reduction

- 6 Star Energy Modelling Rating for apartments

(Class 2 and 4 sole occupancy units) 2

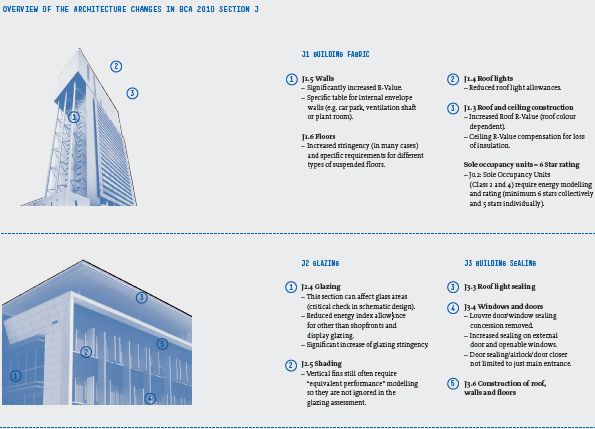

Section J was introduced into the BCA in 2005 to regulate energy efficiency in building design for Class 2 to 9 buildings (Volume One). The intention was not to establish best practice, but to set the minimum benchmark and to eliminate poor building design. The main sections of interest to architects include J1 – Building Fabric (Walls, Roof, Floors, etc.); J2 – Glazing; and J3 – Building Sealing.

One of the fundamental changes is that the scope of Section J has been widened to include the reduction of greenhouse gases, not just the regulation of energy efficiency: “Due to the need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, a new Performance Requirement has been added to require a building’s services to use energy from a renewable source or a low greenhouse gas intensity.” 3 Applicable to heating, this push towards renewable energy and cleaner fuels is expected to have implications in terms of plant space allowances (for example, a gas boiler needs more room than an electric duct heater). Following is a discussion of the available options.

Option 1. DTS – The Prescriptive Approach

The Deemed-to-Satisfy (DTS) provisions are prescriptive by nature, applicable to “normal” buildings and “standard” construction, with relatively small window-to-wall ratios, and predictable wall, roof and floor construction. The increase in stringency of these provisions is significant and is summarized in the main diagram. Following are some of the significant implications on core architectural elements.

Indoor–Outdoor Connection: Glazing ABCB stakeholder information documents indicate “approximately 20% lower glazing allowances” for BCA 2010. Although this is an overall summary, it is important to understand the implications for your climate zone. Below is a like-for-like glazing comparison for an East Sydney office.

This graph indicates that a significant reduction in facade glazing will be imposed, unless other design strategies are employed. Improvements may be required to maintain the same area of facade glazing, such as external shading or lowering the Solar Heat Gain Coefficient of glazing used. Keep in mind, under BCA J2.4, glazing is assessed separately “for each orientation of each storey”. Unfortunately this means architects cannot trade or average between orientations or storeys. It should also be mentioned that many vertical shading fins are ignored in the J2.4 glazing calculator (unless of course they comply with the stringent “80% rule” in J2.5 [b] [i]). Some ESD engineers can provide equivalent performance modelling as a dispensation where required.

Building Envelope Design

“Building Envelope is the core principle of BCA Section J compliance for Architecture.” Architects are encouraged to start with a quick “envelope diagram” during schematic design to capture scope.4 In many cases extra insulation is required, affecting not just your specification but your design drawings. The table below shows a few comparative examples (applicable to “envelopes” for a Brisbane office).

Option 2. JV3 Energy Modelling – The Flexible Approach

Due to increased stringency of DTS methods, understanding the flexibility of this option is important.

The intent of JV3 is to assess the performance of the building as a whole. The result is that the effective performance of one building element can be offset against the poor performance of another. For example, the heat gain via a non-compliant fully glazed facade can be compensated by increased insulation in the roof.

However, underperforming architecture cannot be compensated by over-performing services design.

“The fundamental implication of the increased stringency to the architecture profession is that early incorporation is now more essential than ever.”

For architects, the benefits of this approach are considerable, and include:

- Flexibility – as well as the ability to “trade off” energy performance of the various architectural elements, this also allows architects to use (and get credit for) passive solar design strategies which they have been using for years (before BCA Section J was even thought of).

Also, JV3 now incorporates a concession for on-site renewable energy.

Similar benefits are available for building services, designed to give engineers the flexibility to “trade between” the energy performance of chillers, pumps, airconditioning units, exhaust fans, lighting, et cetera – all of which cost your client money.

The other major advantage of the JV3 verification process is that if the project is targeting a NABERS or Green Star rating, the energy modelling will be undertaken anyway, and a similar model can be used for both purposes.

It is not a matter of if, but when.

The process can be managed to avoid unnecessary redesign and variations. At EMF Griffiths we recommend the following general approach for early design:

- Project proposal stage.

What do you provide in your standard fee letter? (Define the limit of your scope, for example in architecture joint ventures).

Consider offering “energy modelling, the flexible alternative”

as an additional service and explain the advantages in flexibility, value management and potential for energy optimization. Ask your preferred ESD engineers to give you a budget estimate and some words for this section of your proposal.

Firstly, conduct a client briefing. Does the client understand what BCA Section J is and the options available? Secondly, determine the method of compliance (DTS or JV3) with the client and decide on the plan of attack to ensure design team participation (including consultant demarcation). Involve your ESD engineers for a few quick consultations. If the project is a refurbishment, seek confirmation of the extent of compliance required for existing building.

- Scope – Define the scope of architectural compliance and incorporate in cost plan (envelope diagrams assist with this).

These steps should be followed up by a compliance assessment during schematic design (preliminary) and throughout design development.

What about efficiency of time?

Does it sometimes feel as though the wheel is being reinvented on each project? For some of the more subjective elements of design, this is to be expected, but for something as defined as Section J, there is a better way. Here are a few tips to save you time:

- Standard incorporation plan – develop a standard pre-design-planning insert to encourage incorporation of Section J into the project.

- Drafting – prepare a couple of pre-complying, commonly used wall types for your climate zone. Don’t wait for the engineer’s report for wall and insulation requirements after the walls are drawn (avoid preventable re-drafting work!).

- Guides – generic glazing selection and percentage area guides (for various glazing and shading combinations).

- Interactive engineers – choose your Section J engineer early and carefully. Involving your Section J engineers during early design helps draw together the fundamental requirements for the project.

Look for engineers with an interactive approach as you need more than just a weighty compliance report. - Standard specification: there are approximately twenty-five clauses in BCA Section J1–J3 that can be covered by a standard specification note (with only minor modifications required between projects).

The final verdict

BCA Section J is relevant to architects and the stringency increases will significantly affect the architecture profession. Early consideration of options will help ensure a smooth transition into these requirements, and allow for the implementation of sustainable and inspired architecture.

Wes Mergard is an ESD engineer at EMF Griffiths.

NOTES

1. Most, but not all, states have incorporated the 2010 provisions for commercial buildings on 1 May. Only some states have adopted BCA 2010 Section J for Class 2 and 4 buildings.

2. Information sourced from pages 6–8 of “Supporting Commentary on Proposed Energy Efficiency Amendments,” BCA 2010 Volume One from www.abcb.gov.au. and “AIRAH Information Workshops on Section J (Volume One)” from wwww.airah.org.au.

3. Extract from “List of Amendments” in clause JP3 from BCA 2010 Volume One.

4. “Envelope” includes the boundary between conditioned and non-conditioned space. See full definition in BCA Part A1.

All information is provided as a guide only.

SECTION J — YOUR QUESTIONS ANSWERED

Architecture Australia and EMF Griffiths invite readers to submit their questions on Section J. The ten questions that indicate the core issues for architects will be answered by EMF Griffiths in a follow-up piece in the magazine. Questions should be general rather than project-specific. Submit your questions to aa@archmedia.com.au.

FURTHER INFORMATION

EMF Griffiths

EMF Griffiths is a multidisciplinary building services team that provides a unique interactive approach to design.

Contact Wes Mergard.

P 07 3254 2788

W www.emf.com.ao

E wesm@emf.com.au

Australian Building Codes Board

A joint initiative of all levels of Australian Government and includes representatives from the building industry.

W www.abcb.gov.au