Public Sydney: drawing the city by Philip Thalis and Peter John Cantrill / Sydney Living Museums and University of New South Wales.

As a large and beautiful book Public Sydney: drawing the city recalls William Hardy Wilson’s Old Colonial Architecture in New South Wales and Tasmania (1924) and other folio-sized books produced by architect authors such as Andrea Palladio, James Stuart and Nicholas Revett, and Richard Phené Spiers. Their luxurious size was dictated by the reproduction of drawings at a scale where maximum information might be imparted – like the encyclopedic data provided by a map or an atlas, or an architect’s working drawing. The size of Public Sydney has been determined by the scale of Sydney’s plan view and special note should be made of the book’s consistent placement of historic drawings – very carefully done – so that at various moments one can deduce a longitudinal account of the city’s development.

Public Sydney is also a love story. Its authors Philip Thalis and Peter John Cantrill demonstrate a fifteen-year love affair with Sydney, an achievement of devotional documentation paralleled only by Joseph Fowles’s elevational study of 165 years ago, Sydney in 1848. It is important to note that Thalis studied in Paris under Bernard Huet, advocate of Bruno Fortier’s famous Atlas of Paris, and Cantrill studied at IUAV in Venice, where the pioneering work of urban morphologist Saverio Muratori was hugely influential. These studies emphasized the deliberate disinterest or neutralizing of content of the drawing and its power as an analytical tool, enabling urbanists to study a city’s morphology and its defining characteristics at a single point in time – in a way, to find its structural rather than social DNA. This is a very European tradition, documenting the city so that others might work on it with successive zeal. While some in the architectural cognoscenti might scorn these practices as outmoded, there is no doubt that such painstaking research creates an exceptional document for future architecture and urban design.

The focus of Thalis and Cantrill’s mapping has been the public buildings and places of Sydney. Compiled over many years with the help of 150 students from the University of Technology, Sydney and the University of New South Wales, plans, elevations and sections of nearly one hundred buildings, monuments and infrastructure works are presented here. The choice of the word “public” – whether it denotes a building or space – is important. It’s almost as if the act of recording is an act of resistance, a strategy to halt the onslaught of change or at the very least to usefully slow modernity’s inexorable flux through urbanization. Alec Tzannes in his introduction uses the term “stewardship”: the right word for anyone in control of a city. Thalis and Cantrill refute the accusation that Sydney was unplanned. Indeed, it was not, but as a city it has evolved as a series of unfinished and constantly shifting plans, of overlaid and sometimes competing ideas, which this book now captures in a single volume.

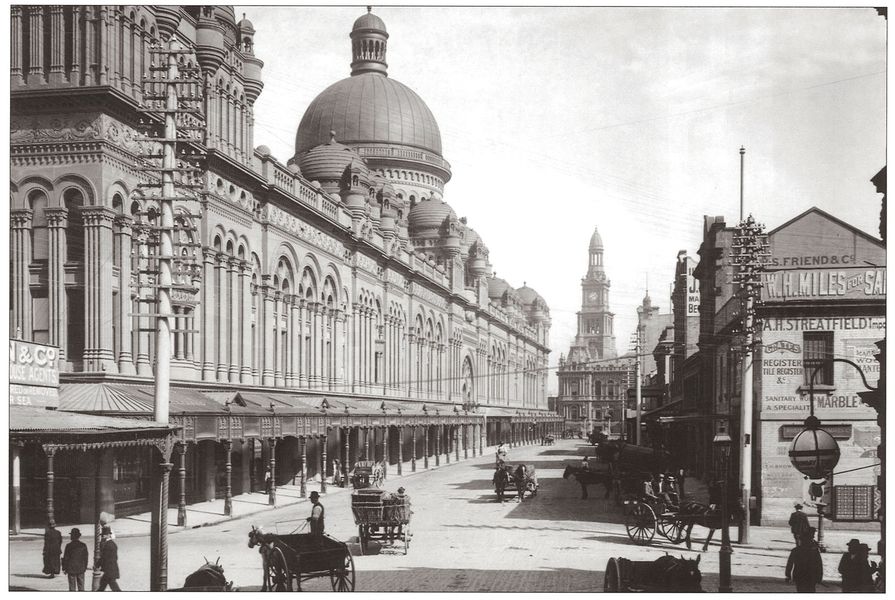

Two essays introduce Public Sydney. The first, by Thalis, is an impassioned definition of what constitutes the idea of the public project. It sets out a clear methodological framework for the research. The second, by Cantrill, is a detailed description of Sydney’s formation and it is here that historic maps on each facing page of text illuminate the city’s gradual formation. These culminate in the exquisite new map of the present-day situation and it is from this point that the book begins in earnest with maps, plans, sections, elevations, original photographs and descriptions of central Sydney’s most important public places, from the Sydney Opera House to the tiny Busby’s Bore Fountain in Hyde Park. There is a double page of sections showing the volumes that Thalis and Cantrill describe as “public rooms” as well as a double-page spread of elevations, all drawn at the same scale.

The essays that follow round out the volume. Peter Mould gives a fine account of the role of government patronage, especially through the Government Architect and the NSW Public Works Department. He rightly marvels at Macquarie’s commissioning of Francis Greenway in 1818 to design an obelisk from which to measure distance to all parts of the colony. Thalis and Cantrill describe this monument as the omphalos – the bellybutton of English conquest and the colonial project. Lisa Murray charts the work of the City Architect and highlights the city’s role in providing for the public everyday – markets, baths and powerhouses as well as roads, parks, street trees, lights and public toilets. She also discusses the place of gender in the city. Lawrence Nield outlines the gradual squaring off of Circular Quay, which, in characteristically frank style, he observes “represents all the deeply flawed processes of planning that have become the norm for Sydney.”

Craig Burton describes the roles of nature, landscape and the pattern of Indigenous settlement in Sydney’s formation. He makes the compelling analogy that “the Sydney area [is] shaped like the back of a human right hand.” Especially revealing are his diagrams of the Tobegully and Tarra ridges east and west of the Tank Stream, which embraced the original settlement. Ian Innes details concepts of nineteenth-century “improvement,” especially through the development of the Botanic Gardens and the Domain. Stephen Collier, using Manuel de Solà-Morales’s phrase “the territorial floor of the city,” hints at other ideas and connections beyond the public building – in many respects tantalizing readers with this book’s potential as the basis for future design research. Not content to leave it at that, Thalis and Cantrill provide a full comparative chronology of drawings and biographies of the city’s architects as well as a chronology of major design competitions held across more than two hundred years of Sydney’s making.

At the end of all this, you need to take breath. This book has been a mighty undertaking. Clover Moore states boldly in her afterword that “Public Sydney is a compendium of what our predecessors got right.” Sydney is beguiling – of that there is no doubt. Perhaps this explains why opinion is so hotly divided over the city’s direction and accounts for its peripatetic evolution. Thalis and Cantrill’s maps and plans, however, allow architects, urban designers and politicians to take stock, to take the city’s measure. Their book allows opinion to be put aside so that the beauty of Sydney’s landscape, the intricacy of its urban morphology and the diversity and dignity of its public buildings, monuments and places can be put into proper perspective. If the city can be seen for what it actually is, Sydney might recognize and recover some of its innate characteristics, withstand the “storm of progress” and grow to be the “open city” that the authors of this fine volume wish for.

Public Sydney: Drawing the City (Philip Thalis and Peter John Cantrill, 2013. Sydney Living Museums and University of New South Wales. 230pp, RRP $95.)

Read David Holm’s review of Public Sydney.

Source

Discussion

Published online: 13 Dec 2013

Words:

Philip Goad

Images:

Courtesy Sydney Living Museums

Issue

Architecture Australia, July 2013