CITATION FROM THE JURY

Jørn Utzon is an architect whose roots extend back into history – touching on the Mayan, Chinese and Japanese, Islamic cultures, and many others, including his own Scandinavian legacies. He combines these more ancient heritages with his own balanced discipline, a sense of architecture as art, and natural instinct for organic structures related to site conditions. The range of his projects is vast, from the sculptural abstraction of the Sydney Opera House to handsome, humane housing; a church that remains a masterwork with its remarkably lyrical ceilings; as well as monumental public buildings for government and commerce.

His housing is designed to provide not only privacy for its inhabitants, but pleasant views of the landscape, and flexibility for individual pursuits – in short, designed with people in mind. There is no doubt that the Sydney Opera House is his masterpiece. It is one of the great iconic buildings the 20th century, an image of great beauty that has become known throughout the world – a symbol not only a city, but a whole country and continent.

“I like to be on the edge of the possible,” is something Jørn Utzon has said. His work shows the world that he has been there and beyond – he proves that the marvellous and seemingly impossible in architecture can be achieved. He has always been ahead of his time. He rightly joins the handful of Modernists who have shaped the past century with buildings of timeless and enduring quality.

THE LORD ROTHSCHILD, GIOVANNI AGNELLI, FRANK GEHRY, ADA LOUISE HUXTABLE, CARLOS JIMENEZ, JORGE SILVETTI

Sydney Opera House under construction. Photograph John Garth/Max Dupain.

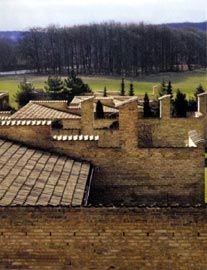

Fredensborg Housing, Denmark (1959–1962). Photograph Keld Helmer-Petersen Photo.

Bagsvaerd Church, Denmark (1973–76). Photograph Arne Magnussen and Vibeke Maj Magnussen.

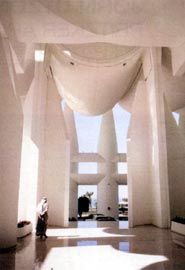

Kuwait National Assembly (1972–1982). Photograph Carsten Bo Anderson.

04 Utzon House in Majorca, Can Felix (1994). Photograph Bent Ryberg/Planet Foto.

IT IS NOT WITHOUT a sense of pathos that one learns that Jørn Utzon has been awarded this year’s Pritzker Prize, architecture’s equivalent of the Nobel Prize. Like the final act in a Greek tragedy, Utzon’s victory is Pyrrhic. At eighty-four years of age, the Danish architect is finally being showered with the honours and adulatory publications deserving of years before.

But not before he designed the Sydney Opera House (1957-73), arguably the best-known public building of the twentieth century and suffered for the greater part of his career because of it. As one of the Pritzker prize jurors, Frank Gehry, remarks:

- Utzon made a building well ahead of its time, far ahead of available technology, and he persevered through extraordinary malicious publicity and negative criticism to build a building that changed the image of an entire country.

In many ways, Utzon’s career charts the tragic path of postwar modernity – from selfcritique in the early 1950s, through practical if uncertain realization, and finally to critical and revisionist redemption by the end of the century. The 1956 competition for the Sydney Opera House gave Utzon the project of the second half of the twentieth century: to achieve the promise of monumentality, which prewar modernism had not realised. His Kingo (1957-60) and Fredensborg (1962-63) courtyard houses became seminal alternatives to the seidlung and forecast the retrieval of place. His Bagsvaerd church (1968-76) gave Kenneth Frampton the built example for his theory of critical regionalism. His National Assembly Building in Kuwait (1971-83) gave new meaning to the image of governance in the Middle East. His unbuilt Asger Jorn Art Museum in Silkeborg (1963-64), semi-submerged and amoeba-like in section, still remains one of the most intriguing reflections on the nature of enclosed space.

Utzon’s seminal piece of theoretical writing appeared in Zodiac 10 in 1962. “Platforms and Plateaus: Ideas of a Danish Architect” indicated Utzon’s rich formal inspiration that was not the machine but the human-built plateaus of Aztec architecture and the timber platforms of Japan.

It was paralleled by his developing interests in Islamic architecture and the tectonic workings of the twelfth-century Chinese building manual, the Ying-tzao-fa-shih, which lay behind rationale for the structural and detail systems of the Opera House. In 1967 Sigfried Giedion in his fifth edition of Space Time and Architecture cast Utzon in the role of the next titan of modernism. It was a tragic spell. Today, amongst young architects, historians and theoreticians, Utzon’s career trajectory is held aloft as an artistic ideal – but as a practice ideal it seems tragically out of touch with a brutal and mercenary political and construction culture.

Like many heroes, Utzon’s self-imposed exile on Mallorca has completed the poetry of his extraordinary career. He and his buildings have, rightly, defined the meaning of legend in the history of twentieth-century architecture.

PHILIP GOAD IS PROFESSOR OF ARCHITECTURE AT THE UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE.