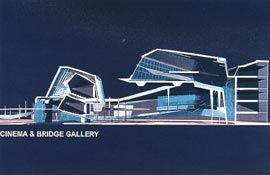

Entry by Shane Murray and Sinclair Knight Merz.

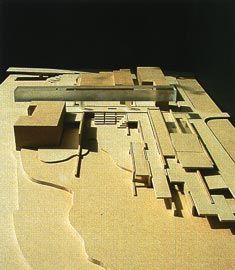

Entry by Edmond and Corrigan.

Entry by Planet Design.

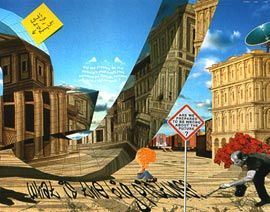

Entry by ARM.

Entry by Elizabeth Watson-Brown, Paul Hotstan, James du Plessis, George Kerr, Richard Buchanan, Phil Tillotson and Gail Pini.

There is a delicacy to the French term salon des refusés that conveys a range of connotations that are not so subtly, nor so neatly, formulated in the English “exhibition of rejected art”. The word refusés is the key.

It implies a scale of descriptions from the diplomatic to the blunt: from the mild verb “to refuse”, in the sense of “to decline something offered”, to the brutal adjective “refuse”, in the sense of “worthless rubbish”. What, then, would be the incentive for an unsuccessful competition entrant to show their work in such an exhibition? Is it in a spirit of celebration, or of commiseration? At the opening of the salon des refusés for the Queensland Gallery of Modern Art Competition, the emphasis was clearly celebratory.

The exhibition was organised and facilitated by Andrew Wilson, a lecturer at QUT and one of the entrants, with the commendable aim of “fostering the idea of the display of unbuilt work in the local architecture culture”. It was held at Metro Arts, a “neutral” gallery space not associated with the competition procedure, and thus a suitable venue for the competitors to symbolically reclaim their work after the rigours of the competition process. In fact the exhibition was also a dénouement in that it revealed the authorship of the anonymous first stage entries, allowing competitors to effectively “sign” their schemes for the first time.

The exhibition came together in a very short time, so there was little chance to gather a full and comprehensive range of the original work. This was in spite of the fact that late material was accepted up until five minutes before the opening – a policy well in keeping with the impromptu spirit of the event. The exhibition was thus dominated by local entries, including a wall of schemes contributed by staff of the architecture schools in Brisbane, and their respective student collaborators. Given the relatively small proportion of the total competition entrants on show, it would be unwise to attempt general conclusions about the quality of the work entered for the competition as a whole. But there are other observations to be made. Interestingly enough, given the phenomenon that is the “Bilbao effect”, there were few schemes that employed the heroic formal gesture.

This generalised resistance to the enticements of the spectacular, especially given the prominent site, was perhaps a result of the competition procedure – the fact that it set out to select a designer or designers, rather than a specific scheme. It is interesting to contemplate whether this significantly affected the designs – the temptation was surely to maximise the transparency of the design process, to render the design decisions and strategies as explicit as possible, and thus to assist the jury to see “through” the scheme to the design ideas behind it.

ARM’s entry was the only one on display that took this aspect of the competition literally – their “scheme” was a kind of visual position statement, a collage of fragments, questions and ideas, rather than a design.

But there was an almost sheepish character to the accompanying text – a written defence against charges of being a “cop out” – which belied the bravado of the work. And, with its pastiche of references to contemporary and historical artists and artworks, and a composition centrally organised around Piero della Francesca’s Ideal City superimposed over the ubiquitous ARM knot, the poster came strangely close to self-parody.

But ARM’s provocations were not the most surprising text on display; surely it says much about the state of architectural rhetoric, if not architectural design, that the most startling thing written on any of the panels was Edmond and Corrigan’s sincere aspiration to create something beautiful – a beautiful architectural object. This entry, along with the Shane Murray and Sinclair Knight Mertz scheme, was clearly one of the most serious contenders on display. It enfolds a central courtyard space, linked to the riverside landscape, in a patterned and patinaed copper plane. Form is created by bending and twisting these planar elements into complex relations, and the richness of the scheme is best understood in section.

In the Murray scheme walls again wrap over, this time to form the roof of a simple box form, but these walls are made of repeated linear elements, as if the whole building is sheathed in oversized vertical louvres. The articulations in this grille are built up through a series of bends in two dimensions. This creates illusory visual effects and gives the impression of a continuous folded surface made from a broken series of independent lines. There is a hard edge to this scheme that bears more resemblance to the patterns of an electronic circuit board than to any architectural vernacular, but the modulation of light through the walls and roof does have a glancing similarity to the local tradition of timber hit-and-miss battens.

The design by Elizabeth Watson-Brown and collaborators also presents an interesting take on this famously Brisbane preoccupation – they describe their scheme as “a dreamlike realisation of the local obsession with the play of light”. Another local, Russell Hall, won’t have disappointed his fans with a design true to his inimitable style – his building centres around a permanently installed crane. Planet Design, in a brave and counter-typical move, house the subsidiary functions of the gallery in a series of towers anchored off a main building volume.

From the first salon des refusés, instituted by Napoleon III as counterpart to the mainstream Paris Salon of 1863, it has often been rejected work, rather than the sometimes trudgingly pedestrian academic art of the Salon proper, which has both drawn the crowds and proven to be truly influential. In the history of painting, the salon des refusés has played an important role as a testing ground, both for work that fell below and work that fell outside the limits dictated by contemporary criteria for judgement. It was a point of honour for the early modern avant-gardes to be rejected by the establishment, and to have their work thus marked as radical, subversive, and ahead of its time. The salon des refusés has historically displayed work that challenges the very grounds upon which “good” and “bad” work is discerned. I would not say that any of the schemes exhibited at this, most recent, architectural exhibition are in the league of Manet’s Dejeuner sur l’Herbe, the star of 1863. But perhaps that is always the secret hope in a salon des refusés: that the “true” winner, languishing amongst the rejected schemes, will be at last recognised and redeemed. Thus Saarinen’s fateful retrieval of Utzon’s Opera House scheme from the reject pile will be mythically repeated, and the rest, as they say, will be history.

Naomi Stead is an associate lecturer in architectural theory, philosophy and cultural studies at the University of Technology, Sydney