morphe: nineteen97Biennial conference for oceanic architecture and design students, at Deakin University, Geelong, Victoria, 6-11 July 1997.

This was no holiday, even if it did offer a tour along the Great Ocean Road and lunch at Surf World. Behind morphe’s playful title lay a very ambitious program which brought together over 600 architecture students to see 16 of the world’s most influential emerging architects. Squeezed into just five days and nights, the conference guaranteed an inspirational adrenaline rush for impressionable students. The stained glass skylights of Deakin’s Great Hall cast an almost sacred light over the proceedings. Highly venerated architects, including Wiel Arets, Itsuko Hasegawa and Ben van Berkel, confirmed their reputations by showing works largely published. Other speakers exploited the theatre of the event to woo the crowd. Greg Lynn thrilled his audience with spectacular computer animations and intricate laser-formed models. Marcos Novak appropriately gave his lecture on cyberspace from his laptop computer. Mark Rakatansky was well received after showing Chuck Jones’ cartoons to illustrate his ideas on movement and meaning. Sarah Chaplin and Eric Novak drew gasps and roars showing the latest in Las Vegas architecture, picking up where the Venturis left off while firing a few shots at Darling Harbour and Crown Casino. Mark Goulthorpe attempted paradoxically to speak of architecture’s ability to communicate what cannot be said by performing a poetic word ballet around his slides to invoke his architecture. Sylvia Lavin received many laughs as she tackled the psychological claims surrouding architecture—from Wilhelm Reich’s ‘Orgon Box’ (an energy treatment room to improve your sex life) to the houses of Richard Neutra (thought therapeutic by being open to natural elements.) This full program left little time for discussion, which made the conference more of a tour-de- force of architectural energy than an educational forum. After sitting in a dark hall for days of inspiring though highly rarefied lectures, I began to understand what being inside Reich’s lead box might be like. I missed the sun and longed for something more Neutra-like; a space which brought closed domains together and engaged its environment. Perhaps I was not alone. A few student questions like ‘who are you?’, and ‘how do you define architecture?’, threw the speakers but were perhaps intended to find some fundamental relationships with students’ positions, and help to understand how these unique solutions had answered common architectural problems. Sadly, too few speakers sensed the occasion of addressing a student audience, and too little time was left to put separate ideas to work on shared concerns. If this had happened, perhaps we might have seen a more impressive morph: of morphe itself. After all, morphing is an act of formation and response to change, or in fact learning, which is the unique condition defining us all as students. Jeff Maas is an architecture student at University of New South Wales and works at Architext in Sydney. MAPInaugural exhibition of furniture by Merchants of Australian Product, at the new Contemporary Design Gallery in the Museum of Applied Arts & Sciences, Sydney, from 11 July, 1997. At last a Sydney exhibition space dedicated to contemporary design— established by the Powerhouse, which has consistently demonstrated in its exhibition content and aesthetics a commitment to advancing Australian work. The gallery has been dedicated to all facets of Australian design, with several exhibitions each year intended to highlight the diversity, quality and talents of our adolescent industry. Launching the gallery is an exhibition of furniture by Melbourne-based MAP [Merchants of Australian Product]. According to curator Judith O’Callaghan, future exhibitions will focus on the productions of furniture designer Caroline Casey, jeweller Susan Cohn, graphic designer Visnja Brdar and the multi-faceted office of Marc Newson. MAP is the frequently copied design and manufacturing team of Christopher Connell and Raoul C Hogg, who have been developing furniture pieces for local and Asian markets since 1989. This exhibition presents all their important works since that time—beginning with the early Mosquito chair and M4 table (which have sustained strong sales), highlighting the much publicised Pepe chair, and concluding with new designs for storage. The exhibition was designed by Lucy Banyan of Banyan Wood, with graphics by Alison Hastie of Nova Design, who developed a family of simple and bold banners using strong contemporary colours that echo the upholstery shades favoured for MAP’s Pepe chairs. The rectangular gallery is simply planned for ease of movement and legibility of individual exhibits. Plinths and displays read as strong cubic forms in pale lacquered boards with aluminium rails and hoop pine-veneered insets, on which the pieces sit. As well as finished works, the displays include plasticine models and prototypes in various stages of construction—these revealing the technological complexities of manufacturing selected designs. In particular, the Pepe chair (sinuous signature of the show) is represented in a sequence of states through design and manufacture— from initial sketches and models to prototypes in different conditions of undress. Thanks to such display strategies, the exhibition provides an excellent insight into MAP’s depth of resolution—not just in terms of aesthetics and form but also technical ingenuity and precision. Connell’s and Hogg’s presence in the Australian furniture industry is significant to those of us who select furniture for commercial and residential uses where style is of great importance but budgets are limited. Although they now have several competitors of their own generation, their catalogue credo—”just do it”—implies a reaction against industry inertia. This appears to be a battle cry from young designers who long ago gave up waiting for established manufacturers to embrace their talents and ideas. Today, the real excitement in our furniture showrooms arises from designers who conceive, produce and market their own works. This represents the first major boost to the Australian industry’s profile since the golden years of Parker in the 1960s—a period of health later overshadowed by the 1970s-1980s boom in Italian imports. Now it is again possible to purchase original, locally made pieces that are equal in style and quality to many European imports: a point proven by MAP’s regular appearances on stands at the Milan Furniture Fair. Tim Laurence is a senior lecturer in interior design at the University of Technology, Sydney. | Sydney As A Pedestrian CityAustralian Institute of Landscape Architects lecture by Richard Leplastrier at the Eveleigh Railway Workshops, 1 July 1997. Richard Leplastrier’s talk to a packed and shivering house was both inspirational and problematic. Inspirational because he has a humility that is uncommon in Sydney; the talk was free of reproach and full of ideas. However, there were problems in both the way his pro-walking, anti-driving concepts were presented and the urban and political contexts in which they must be understood. The opening points were that expansive expressions of space have to be developed and that a model can already be found in Japanese calligraphy—the symbol for ma, which implies space, void, pause, as well as a gate and a house. Such a model could be measured against the divisive, exclusionary, spatial policies which are being adopted in Sydney to discourage pedestrian activities and threaten the textures which now characterise the city. Cited examples included the casino, East Circular Key and the Eastern Distributor. Leplastrier’s critiques and ideas were all based on one powerful reading of Sydney’s topography in relation to his pursuit of pedestrianisation: the relationship between Sydney’s historical movement corridors and the locations of its ridges. As he observed, “it was the black fellas that told white explorers how to cross the Blue Mountains … by following the ridge lines.” He listed Oxford Street, Macquarie Street and other thoroughfares as compelling evidence of landscape’s moulding of Sydney’s form. Before cars and trains, the easiest way to move about the settlement was to stay on the ridges. Those old routes still can be read as the skeletal bones of the city. Ridges were also traversed by Aboriginals thousands of years ago, and their footprints and oar-ripples may be imagined in a contemporary walk from Balmain across the Glebe Island Bridge, across Pyrmont in a saddle running from the fish markets to the old Pyrmont Bridge, up Market Street and across Hyde Park to finish down at Mrs Macquarie’s Chair. This experience is diminished by the blandness of the Glebe Island Bridge and obstructions presented to walkers at critical junctions such as both ends of that bridge, the new abutment to the city end of the Pyrmont bridge, and the abundance of traffic slicing across much of the route. A cacophony of items as useless as the monorail further degrades the experience. To improve things, he suggested reopening the Old Glebe Island swing bridge, re-establishing a strong link to the Millers Point shoreline by simply removing a series of fences and gates from the Aquarium onwards, and creating intersections in the city where pedestrians could take priority. Macquarie Street was identified as a prime target for incremental pedestrianisation to strongly link key institutions and help build a communal sense of civitas. This strategy would also connect the Opera House to Hyde Park and perhaps initiate a chain of parks down to Prince Alfred Park and Redfern. Much was also said for the retention of Sydney’s old industrial buildings; fast-vanishing items on the cityscape. Old Pyrmont was sadly remembered, while praise was given for the reuse of the Eveleigh Rail Yards building stock. His main hope was that state-owned and abandoned commercial buildings, particularly those on the water, could be reinvigorated to contribute to a new public domain focusing on the harbour. The simplicity and plain truth of Leplastrier’s ideas have great power—and many of his proposals only require the consent of those who hold authority to be put on the ground, with minimal recourse to major capital outlays. However, this is where Leplastrier’s most pragmatic ideas founder: Sydney is seemingly ruled and criss-crossed by such a bizarre conflagration of quangos, planning committees, BOOT (builder/owner/operator/transfer) outfits and plain old vested-capital interests that the notion of doing anything but the most irreparable, costly and complex urban operations seems outlandish to those in power. Despite their obvious nobility of intention, the speaker’s more fanciful suggestions came across as naive; like a reading from Christopher Alexander but with less chance of daylight. However, on that frigid night in the railway workshops, when a few hundred of us felt our toes about to drop off, a glimmer of heart-felt hope was expressed in an attitude of warmth. This attitude could generate a new attempt to define a more comprehensive and intimate, and less blaringly iconic, urban self for Sydney. Duncan Gibbs, an RMIT graduate in landscape architecture and urban design, is now in Sydney “subdividing the eastern seaboard”. In or OutNational conference on interior design, arranged by the Queensland University of Technology, at the Queensland Art Gallery and Queensland Cultural Centre, Brisbane, 25-26 July, 1997. In many ways this conference, convened by Dianne Smith of QUT, exposed the profound dilemmas faced by the interior design ‘profession’. The two days embodied a condensed implosion of issues, concerns and suggestions to an audience of educators, practitioners and allied professionals. It was an accurate portrait of a profession without a perception of its own id. Common to other conventions of this type, the conference spent a disproportionate time trying to analyse itself—buttressed by workshops, facilitators and representatives from professional bodies. The question ‘what is interior design’ was dissected, probed, laid out and folded back on itself. I suppose this tendency is endemic of a profession which is not quite a profession but really wants to be one. Like many organisations in a state of incubation, interior design is a culture which seems to be pursuing preventions as outcomes instead of flourishing cures. It is not surprising to witness such cultural inertia because it is mirrored in the sad state of education. Departments and faculties of design in universities have been rendered impotent and rehabilitated into a world governed by corporate policy makers. This is ubiquitous in world education and not solely relevant to Australia! The conference organisers should be congratulated for bringing out the two international guest speakers, John Pawson and Marc Newson, who presented some amazing work: inspiring, unique and challenging. The differences in approach and form were extreme but each were equally powerful. Ironically, these were two designers who did not follow the quality rules of the facilitated methods adopted by industry and education. The organisers also selected a very strong body of national speakers representing practice and education. Peter Geyer and Sue Carr gave lectures and were forward in their participation in other events. Their contributions were supported by memorable talks by Harry Stephens from the University of NSW, Andrea Mina from the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology, Davina Jackson from Architecture Australia and Marina Lommerse from Curtin University of Technology. Ultimately, the conference could be described as a success! It also took place in one of the most exquisite galleries I have been to in Australia, with a formidable collection of contemporary art. After being in such an environment for two days, one cannot help but be affected by some of the products of the creative imagination. John Andrews is Professor of Interior Design at RMIT. |

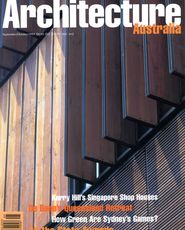

Review: Architecture Australia, September 1997

More archive

See all

A preview of the November 2020 issue of Landscape Architecture Australia.

left Maastricht Academy for the Arts, presented by Wiel Arets at the morphe student conference at Deakin.

left Maastricht Academy for the Arts, presented by Wiel Arets at the morphe student conference at Deakin.