Reflection — Chris White

RMIT University City Campus’s original vision of breaking down the barriers of a “gated educational community,” of opening up and integrating the campus with the city and the community, became the brief for the RMIT University Urban Spaces program. The program has progressively developed over the past ten years, from an initial presentation to the City of Melbourne in November 1996.

The initial collaboration between Peter Elliott Architecture and Urban Design and the City of Melbourne produced the RMIT City Campus Urban Spaces Strategic Plan in March 1997. This set the framework for the development of 11 sectors on the main city block, subsequently expanded to 13 with the acquisition of the legal precinct containing the former Magistrates Court, the City Watch House, and the Police Garage.

When I first joined RMIT University over nine years ago [in 1999], the first four sectors of the program were already complete and the vehicle parking had just been relocated out of Bowen Street, the central campus spine. This had created some discontent, with valuable funds being spent on landscaping, not to mention the loss of car spaces. As the sectors that would eventually renew Bowen Street opened up to reveal a pedestrian and educational core for the campus, the initial concerns disappeared amid a growing sense of pride. RMIT University became a campus integrated with its city. Since then Bowen Street has become the focus for RMIT University’s festive and ceremonial events such as Orientation, Open Day, and Graduation.

Ten years on [2008], the campus has been completely transformed, with only two areas left to implement, once the renovations of the buildings to which they relate are complete. This progressive development has delivered a comprehensive range of benefits from a campus planning perspective. On a broad scale, its unifying framework provides a legible, urban context within which the distinctive RMIT buildings can maintain their individual character, while still engaging as part of a cohesive campus. In large part this is achieved through the application of a varied but distinctive palette of materials, paving, and urban furniture, which has links with the surrounding city streetscape, but sufficient differentiation to signify entry to the campus. This palette has proved to be functional and easy to maintain, and it has a timeless aesthetic that remains as fresh today [2008] as it was ten years ago.

From a facility management perspective, the progressive development of each sector has been used to resolve a myriad of functional problems, including service upgrades, disability access, security lighting, way finding, and, most importantly, maximizing the functionality of space.

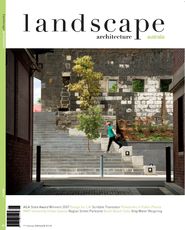

Sector 13. Looking into Alumni Court from the Belvedere.

Image: John Gollings

The quality of Peter Elliott’s work is found in the detailed planning that resolves issues and provides utility and character to the interstitial spaces that make up the urban fabric of the campus. Favourite spaces of this type include the Fig Tree Courtyard (adjacent to the Old Melbourne Goal Chapel), the Belvedere (behind the City Watch House), and most recently the steps that link the Alumni Courtyard (former Police Garage) with the rest of the campus. This recent area provides not only the required linkage, but also an active recreational area with a one-ring basketball court that is never out of use, and a passive seating area adjacent to a new building entry that resolves disability access for this sector of the campus.

In a recent review in The Age, Norman Day perfectly summed up the significant impact of Peter Elliott’s work at RMIT when he wrote, “Along the way, this creative team adds small pieces, over years of contribution, which in time will aggregate to produce a campus of delight.”1 I would only argue that there is already a sufficient body of work to create “a campus of delight,” and that it will just become more delightful in the years to come.

In 2003, an expanded Urban Spaces Framework was developed to encompass the entire City Campus. Its purpose is to ensure that the Urban Spaces program will expand beyond the main city block, as RMIT further develops the rest of the campus, including the Carlton, Swanston Street, and former CUB site properties. RMIT is continuing to discuss with the City of Melbourne the progressive development of the distinctive urban environment that has now defined the RMIT quarter of the city.

Review — Martyn Hook

The landscape architect operating in the public realm generally falls into one of two camps: those concerned with ecology and the bigger picture of landscape; and those focused on the hard elements of landscape, the built, concrete nature of urban fabric. Rarely do these approaches intersect – and when they do, the exceptional often occurs – but the commonality that both camps share is the acceptance that their work contributes to the ideal of public open space. Architects, on the other hand, are often concerned with how their architecture is seen and how it can be measured and assessed. Architects must be clear of the relationship their architecture has with its context and how that relationship may define the work. When architects become involved in urban design, the language of the ideal is distorted – they must set aside an inherent desire for attention and focus on their contribution to building context.

Architect Peter Elliott believes he brings “a sensibility of design” to his landscape projects. “Where the landscape architect may be unable to shift their focus from the ground plane,” he says, “the architect has fundamental attributes to bring which are concerned with the manifestation of built form.” Indeed, this ideology is evident in the epic RMIT University Urban Spaces project, which Elliott and his office have been designing, developing, and building for a long time. The urban campus of RMIT covers four hectares of inner-Melbourne real estate, covering three city blocks at the top of the Hoddle grid, interconnected by a network of open space and laneways. After twelve years [as of 2008] and, in Elliott’s opinion, with at least another three to go, it is worth considering the project and its strategies around defining an urban landscape and creating pleasant public space for around 30,000 students.

Elliott sees his key role as “orchestrating space for sociability.” What he means by this is activating a space in an urban landscape without being prescriptive, allowing activity to be determined by the potential of the space. In this situation, the elements under his control – trees, street furniture, paving, shade – become prompts for public engagement, rather than fulfilling definitive roles. Resolving how a space should work – whether heavily populated or not – becomes a priority, as does ensuring it remains a good place to be even when it’s empty. Essentially, the projects at RMIT involve stitching together the remnant spaces created as the university acquired buildings and land. In this sense, the work is not necessarily about a singular idea – it seeks to provide legibility when moving from one space to the next, developing a cohesive language for the university.

Sector 5. Alumni Court and stairs, seen from building 15.

Image: John Gollings

Some barriers remain between the professions of architect and landscape architect. It would be problematic to categorize Elliott’s key references in this work – Italian architect Carlo Scarpa and Slovenian architect Jože Plečnik – as one or the other. They are individuals who consider and deal with public space in a particular manner. As the work has progressed at RMIT, Elliott’s strategies for “rebuilding a piece of the city in a forensic manner” have also evolved. The intent has become clearer, the detailing modified, and the palette of materials extended. It is still the same project, now divided into thirteen sectors, gradually completed as budget and logistics have allowed. Logically, in light of Melbourne’s acute water shortage, water-reliant planting has been reduced; this has proven a controversial point. “Development of a collection of urban spaces has never really been about landscape in a purist sense,” explains Elliott. “All the elements, even the plants, have been exploited for their architectural nature. A well-placed tree or a creeper on a wall embraces a strategic use of planting, understanding the way that the planted elements of the space are not obligatory, but complementary. They add to the space, rather than make it.” Due to the urban nature of RMIT’s campus, it is impossible to assume that a plant will be tended, so the survival of a plant becomes a war of attrition – it must be tough enough.

Those of us who haven’t been to university recently may not understand what a critical, often desperate place it has become in terms of funding, budget cuts, student management, facilities management, and public space management. To maintain a project about public space amid this turmoil is remarkable. Some might argue that Elliott has used his similar work at the more controlled and salubrious surrounds of the University of Melbourne as a test bed for his tougher work at RMIT. But unlike the classical academic gardens up the road, RMIT is a working piece of city, not a refined facsimile of an ideal. It seeks partners in the urban fabric, as fingers of the campus infiltrate the city, cementing its relationship in a manner both parasitic and contributory. When Elliott began the project in the early nineties, much effort was made to identify the successful elements of the urban design component of the Melbourne City Council – which was highly regarded at the time – absorbing their design manual, pulling it apart, and deciding which parts to take. By carefully selecting and manipulating the suite of elements, Elliott has developed a vocabulary that builds on the city, but refines it. Bins, benches, bike racks, bollards, paving, stone, drainage grates – the often invisible but essential bits of city fabric that define the quality of the urban environment have been seized and interrogated by Elliott’s team and grafted into the RMIT spaces. Where once RMIT borrowed from the city’s urban design ideas, it now appears the city is looking at RMIT as the benchmark for how to continue its work. The real success of the project comes courtesy of the persistence and patience of the client and the fact that all the work has been allowed to be the product of one hand.

The Urban Spaces project unites the architecturally exciting and eclectic RMIT campus through the ground plane – but, in fact, this is a plane that slips up the sides of buildings, disappears, then bobs up around the corner, is sat upon, leant against and driven over. It is a horizontal surface that becomes spatial and evocative simply through the dexterity of its author. As Elliott describes it, the RMIT campus becomes a “sophisticated understanding of urban existence … quite gritty and very pleasurable for that!”

Timeline of works

1996–1999

Sector 1: Bowen Lane (and lanes between B8 and Storey Hall, B2, B4, B6)

Sector 2: Ellis Court

Sector 3: Bowen Street (Ellis Court to Franklin Street)

Sector 4: Bowen Terrace (adjoining Bowen Street and B8, B10, B12, B14)

Sector 7: University Way (lane behind B5, B7, and B9 connecting to Franklin Street)

2000–2007

Sector 13: The Belvedere (terrace at rear of Former City Watch House and lane next to B20)

Sector 12: Alumni Court

Sector 5 (North): Stairway to Alumni Court (adjoining B15)

2008–2009 (future works)

Sector 5 (South): University Lawn (behind B3 & B1)

Sector 6: B1 court (to be done with B1 refurbishment)

Sectors 9, 10, & 11: North East corner (around B13 to be done with refurbishment)

Credits

- Project

- RMIT University Urban Spaces, City Campus

- Architecture and urban design

- Peter Elliott Architecture + Urban Design

Melbourne, Vic, Australia

- Project Team

- Peter Elliott, Rob Trinca, Ron Jones, Anna Ely, Geoff Barton, Sarah Drofenik, Helen Day, Gina Levenspiel, Tim Black, Tony Charles, Craig Douglas, Sarah Newton, Rob Troup, Eldo DiMuccio, Justin Mallia, Sean Van der Velden, Catherine Duggan

- Consultants

-

Architecture and urban design

City of Melbourne

Building surveyor BSGM

Hydraulic engineer Rimmington and Associates

Landscape architect Urban Initiatives

Quantity surveyor Slattery Australia

Services engineer Umow Lai

Structural and civil engineer Clive Steele Partners

- Site Details

-

Location

La Trobe Street,

Melbourne,

Vic,

Australia

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Category Education, Landscape / urban

- Client

-

Client name

RMIT University

Source

Discussion

Published online: 2 Feb 2008

Words:

Martyn Hook,

Chris White

Images:

John Gollings

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, February 2008