“On the one hand, a work of architecture … can be characterized by a condition of uniqueness … On the other hand, a work of architecture can also be seen as belonging to a class of repeated objects, characterized, like a class of tools or instruments, by some general attributes … the essence of the architectural object lies in its repeatability.”1 – Rafael Moneo

If there is one aspect of architecture that garners considerable public appetite, well nourished by our media, it is the one-off dwelling. The vivid details of another person’s life – often stylized – fuel the aspirations of Australian homeowners. Kerstin Thompson Architects (KTA) houses are among these stories about uniqueness: of client demands, site specifics, neighbourly battles and planning triumphs. But if we widen our gaze beyond the particular merits of each, and instead take in groupings of these mainstays of architectural practice in Australia through the lens of typology, what lessons, if any, might the single house offer a discussion about housing futures?

According to Birkhauser’s Floor Plan Manual Housing, not much.

“The single family house involves no spatial formations in the urban planning sense and it is also uneconomical because of its high individual costs, its high consumption of property and the sprawl it creates …”2

On the basis of this scathing critique, we might even go so far as to say that the single house is not the future – an architectural endeavour further discredited by some in the profession as not “real” architecture because it apparently has no “urban consequences” nor “honorific program.”3 Of course, housing does have considerable urban, suburban and ecological consequences. In volume alone it is the majority of current construction activity.4 Our house is part of the street is part of the suburb is part of the city. The quality of each one matters in the making of the greater composite that is a neighbourhood.

Fitzroy Townhouses by Kerstin Thompson Architects. By relinquishing control over the interior fitout the occupant is encouraged to stamp the space with their own identity.

Image: KTA

Arguably, the aspect of the house most instrumental in determining quality, both within and beyond the house, is the building shell and in particular its typology. Our disciplinary intelligence and authority should therefore be directed toward this as a priority. Developing or choosing a typology orchestrates the nature of the relationship between public, private and common space, between one household and the next. For in accommodating domestic bliss we are also inevitably forming the civic realm.

In the tradition of the pattern book, might we offer a range of base types for minor customization to satisfy living needs now? The following survey and analysis of a selection of KTA projects – through the lens of typology – identify some patterns for the typology of a building’s shell. Extracted from these are some repeatable lessons exemplified by three houses nominated as case studies – the Upside Down House, the Apartment House and the Living Together Apart dwelling. By de-emphasizing their value as one-off bespoke solutions and instead framing them as types for ready use, they can perhaps be applied to other situations as models for future housing.

KTA survey of typologies

Organized from micro to macro, the survey, a study in relations conducted largely through the plan, commences within the house, then goes around and beyond it.

Separations and connections

The floor plan, as it pertains to household workings, is an instrument for managing privacy, primarily through the arrangement of uses and mode of circulation. It orchestrates desirable separations and connections, and these tend to be between: uses or activities like living/sleeping or working/recreation, adults/children, guests/core household, public/private and individual/group.

Bernard Leupen in Housing Design: A Manual identifies six activities common across most cultures – gathering, sleeping, cooking, eating, washing and working. Western architecture tends to assign these activities to specific interior spaces, e.g. living room, dining room, bedroom, kitchen, utility room, bathroom. A particular room is designated to accommodate a particular use. This is distinct from a traditional Japanese ordering of interior space, which is instead by relationship – main room, small room, medium room next to main room. KTA’s work tends toward the second system but conforms the definition of rooms to the client’s brief, which is usually outlined in terms of uses. The relationship system is preferred because it enables multiple rather than singular uses of spaces. It pursues the notion of the polyvalent dwelling, which Leupen describes as “one that can be used in different ways without requiring adaptations of an architectural nature thanks to the way that activities can be interchangeably carried out throughout the various spaces.”

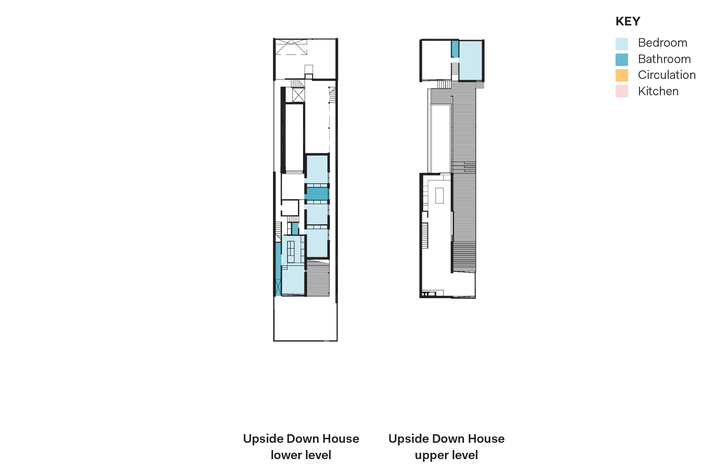

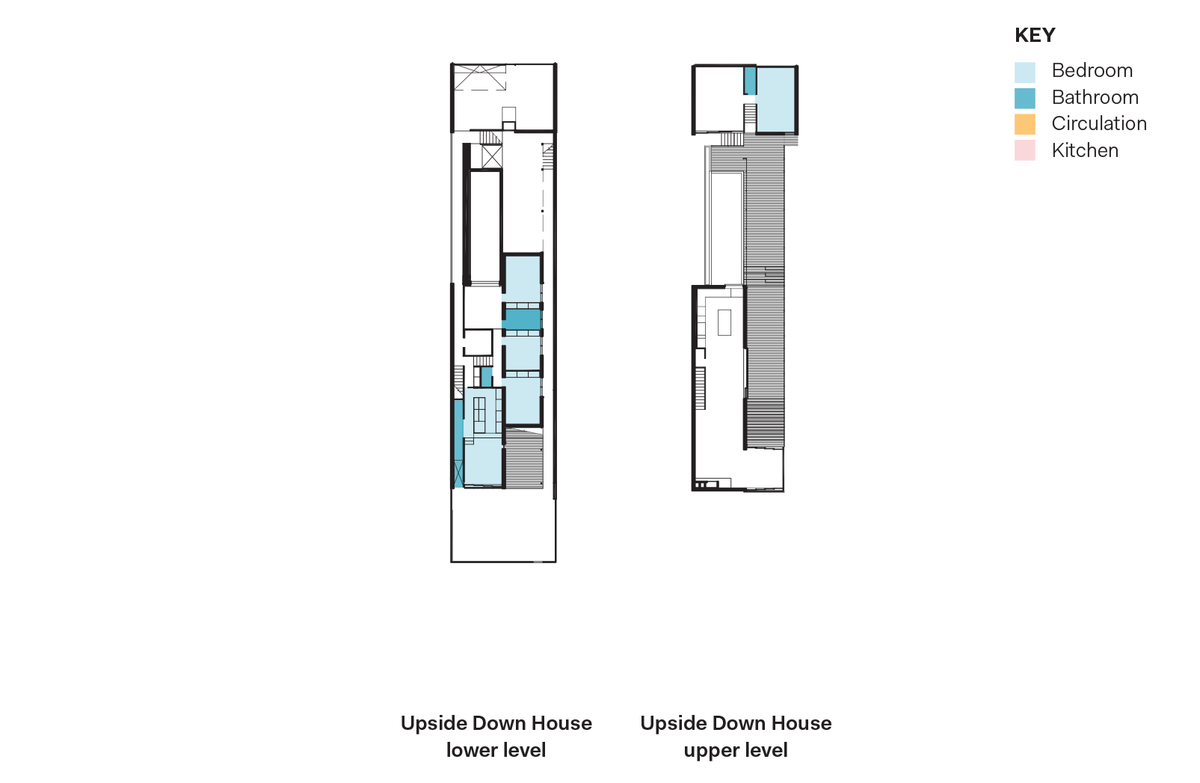

Figure1: The arrangement of private space (bedrooms and bathrooms) in Upside Down House, where the majority of sleeping spaces are located downstairs and the living spaces upstairs.

Image: KTA

KTA’s survey maps the most private spaces within a house by distinguishing between bathrooms and bedrooms (see figure 1) and everything else. There are so many variations of this particular study that we could have undertaken. For example, Louis Kahn’s servant and served spaces, although this would have highlighted the location of typically the most fixed program of all in the house – wet areas, whether kitchens, laundries or bathrooms.

On the privacy spectrum of the house, the bathroom is typically at the most private end. Asking “How many toilets do you think you need?” during a client briefing is a quick way to gauge where a household’s expectations sit in relation to privacy and the degree to which household members wish to be segregated, the amount of friction they can abide.5

Contemporary house design commonly equates its sophistication with an increased number of bathrooms, particularly the ensuite, which directly associates a bathroom with a particular bedroom for its inhabitants’ exclusive use. It is worth noting that a generation ago one bathroom sufficed and a generation before that an indoor toilet was still a notable convenience. Now it’s not uncommon in the one-off house to have one bathroom or toilet per householder. Somewhat perversely, as households shrink, bathrooms proliferate. The days of the queue for shower or toilet, the negotiation over who’s next and moving over slightly to allow another to use the basin are diminished. Yet these negotiations could be considered connection, an opportunity for interaction.

Observable tendencies in KTA’s arrangement of internal spaces include: sleeping down and living up; primary spaces – living and main bed suite – on a single level, especially for older clients who seek to age in place; and separate wings for sleeping and living.

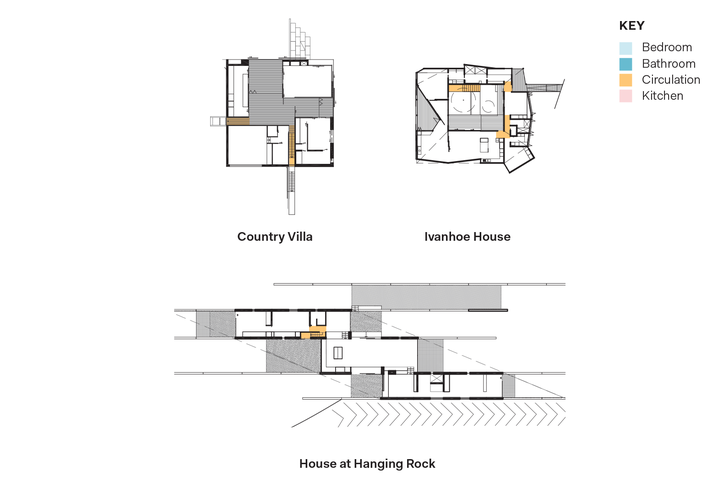

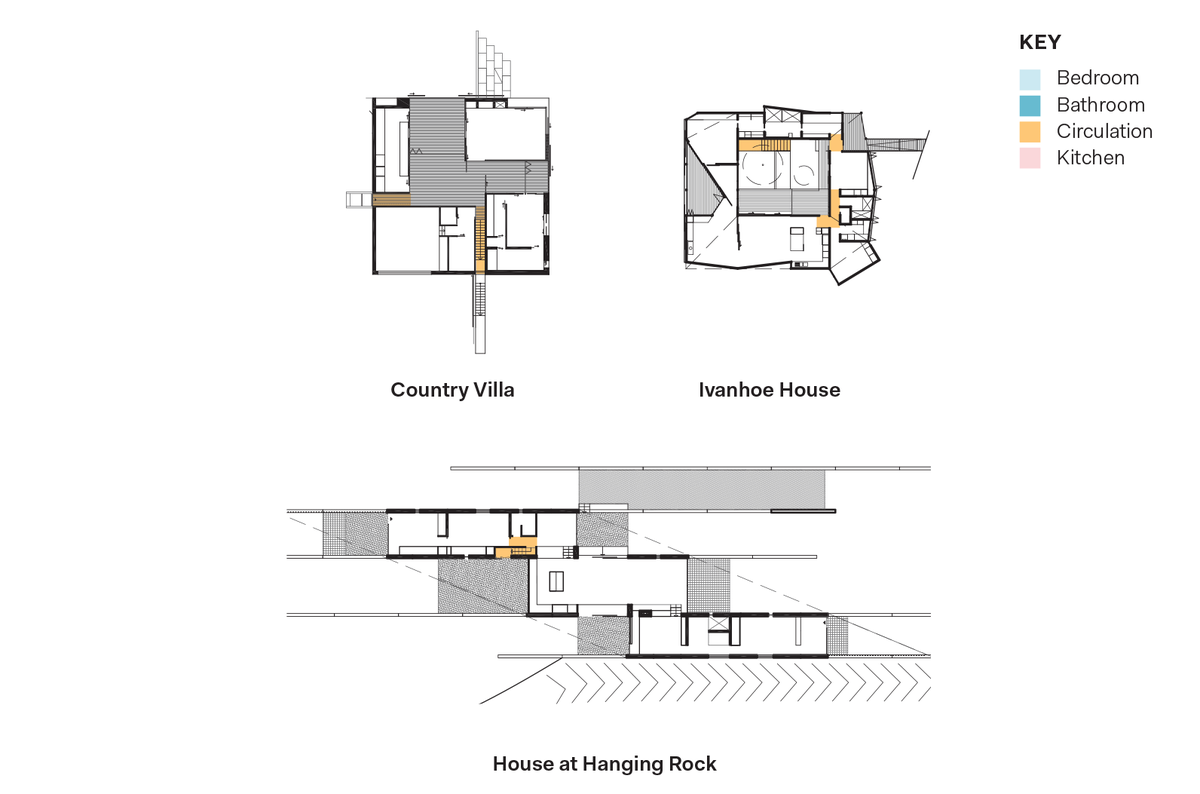

Circulation types include: enfilade linear (thoroughfare rooms linear), enfilade loop (thoroughfare rooms loop), corridor with terminal rooms, centrifugal and hybrid/ other (see figure 2). Discernible patterns in KTA’s plans include a tendency to minimize dedicated circulation space and instead deploy the enfilade. This allows more permeability and filtering between spaces instead of the compartmentalization of corridors and terminal rooms.6 Circulation is incorporated into the primary adjacent space to enrich both, an approach exemplified in Country Villa, where the central hall accesses surrounding spaces as well as serving as the primary gathering space in the tradition of the great hall of Palladian villas. In summary, within the house the mode of circulation in combination with the number of bathrooms and their arrangement significantly influence how a household relates and whether these spaces are planned as opportunities for exchange or withdrawal from household members.

Figure 2: Circulation types. Centrifugal circulation in Country Villa; enfilade loop circulation at Ivanhoe House; enfilade linear circulation in House at Hanging Rock.

Image: KTA

Amenity/dwelling type

Moving now from within the house to within the site, the next survey demonstrated how the building envelope typology enables site responsiveness, especially in relation to climate, orientation a nd integration of interior and exterior space. There are five types common in KTA’s work: detached villa – wall, detached villa, attached villa, townhouse and apartment. Within each of these categories there are of course subtypes, such as the courtyard house. These five types align with shifts in density from low to high associated with larger rural or coastal sites to smaller, inner-urban ones. The detached villa wall type is common to many of our rural projects because the linearity of the planning deploys the building envelope as a wall that has territorial consequences, since it defines and protects the intermediate landscape, especially from wind. On smaller sites, many of our houses are upside down: living on the top and sleeping on the ground (see figure 1). This makes good environmental sense for Melbourne’s conditions – cool sleeping areas in summer, full sun to living areas in the depth of winter. Also, within more constrained inner-city sites, living up provides an enhanced visual aspect from living areas compared with more private and introverted visual amenity via ground-level courtyards to bedrooms. The adaptability of the building envelope extends its climate responsiveness. Operable glazed walls in combination with solar screens can allow the house to open up to or shut down from the elements and they secure the interior for night purging and manage privacy as required.

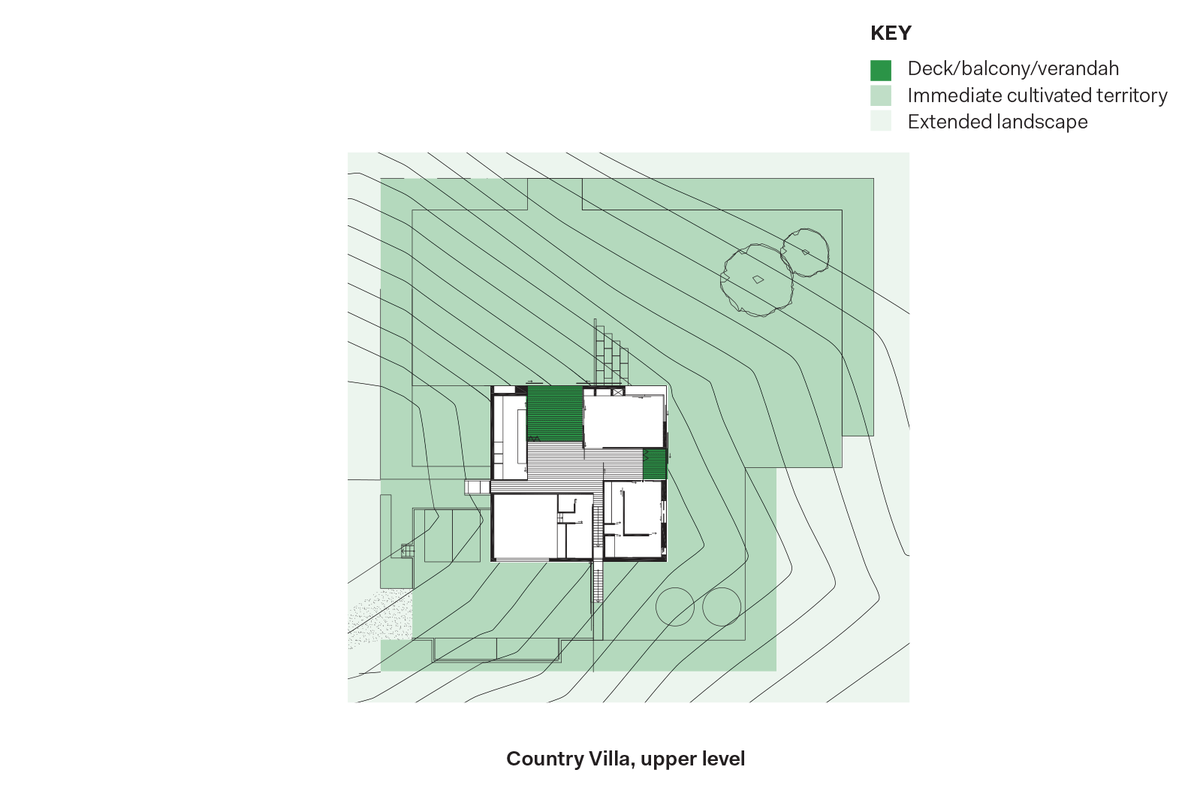

Interior and exterior continuums

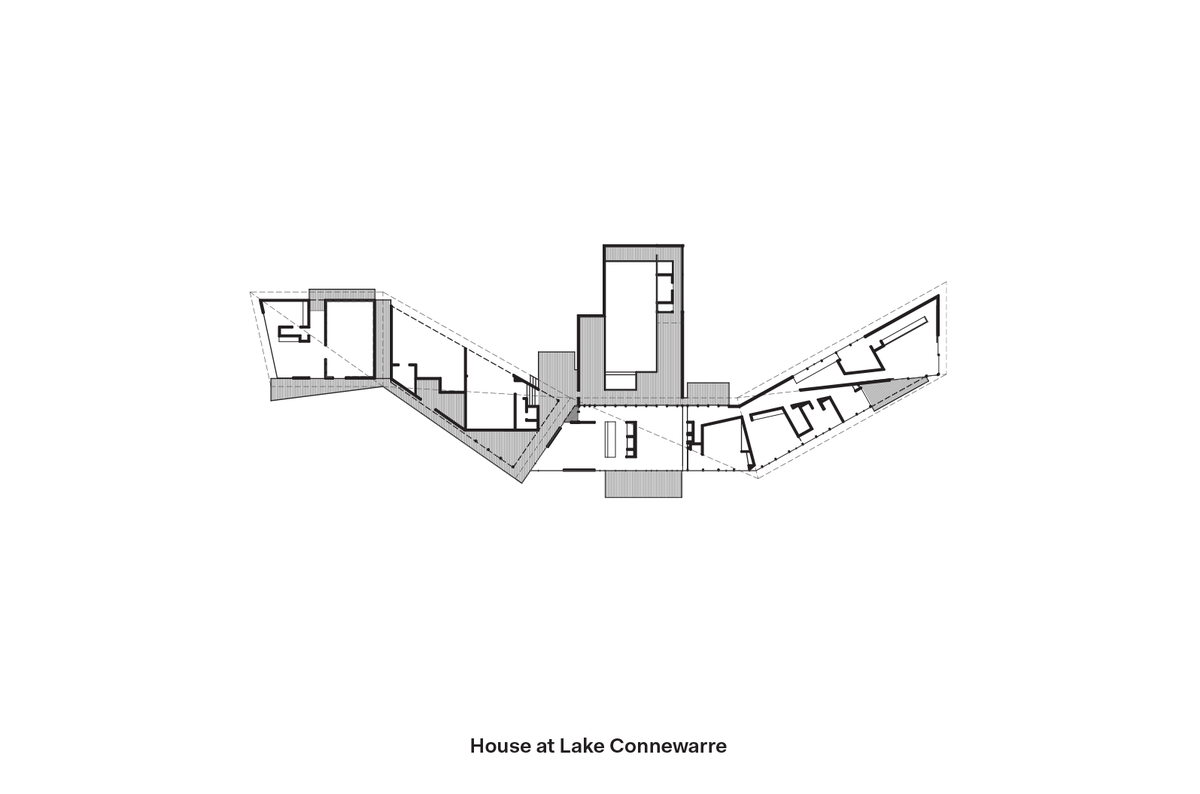

The way in which interior and exterior space relate is a major consideration in the selection or invention of a typology. In larger rural sites, such as House at Lake Connewarre or Country Villa, there tend to be three tiers of exterior space. The first is part of the building, such as decking, balconies or verandahs; the second comprises a cultivated territory immediately around the building that creates a threshold between interior domesticity and the vast, extended landscape that constitutes the third tier. Suburban villas tend to have only the first two. Projects like the Lake Connewarre house act as catalysts for the repair and restoration of degraded farmland, forming a vital link with adjacent sites for an extended ecology. In this way the creation of private amenity can be used as a means to enhance the public realm, whether it’s the street or the broader ecology – a balancing of private retreat and civic contribution.

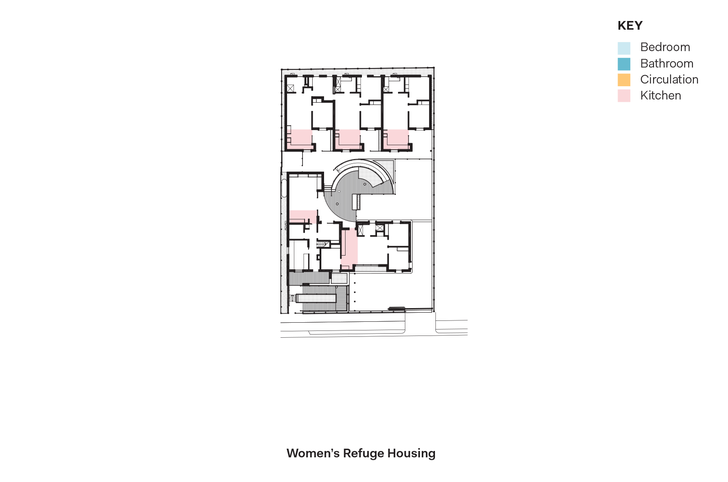

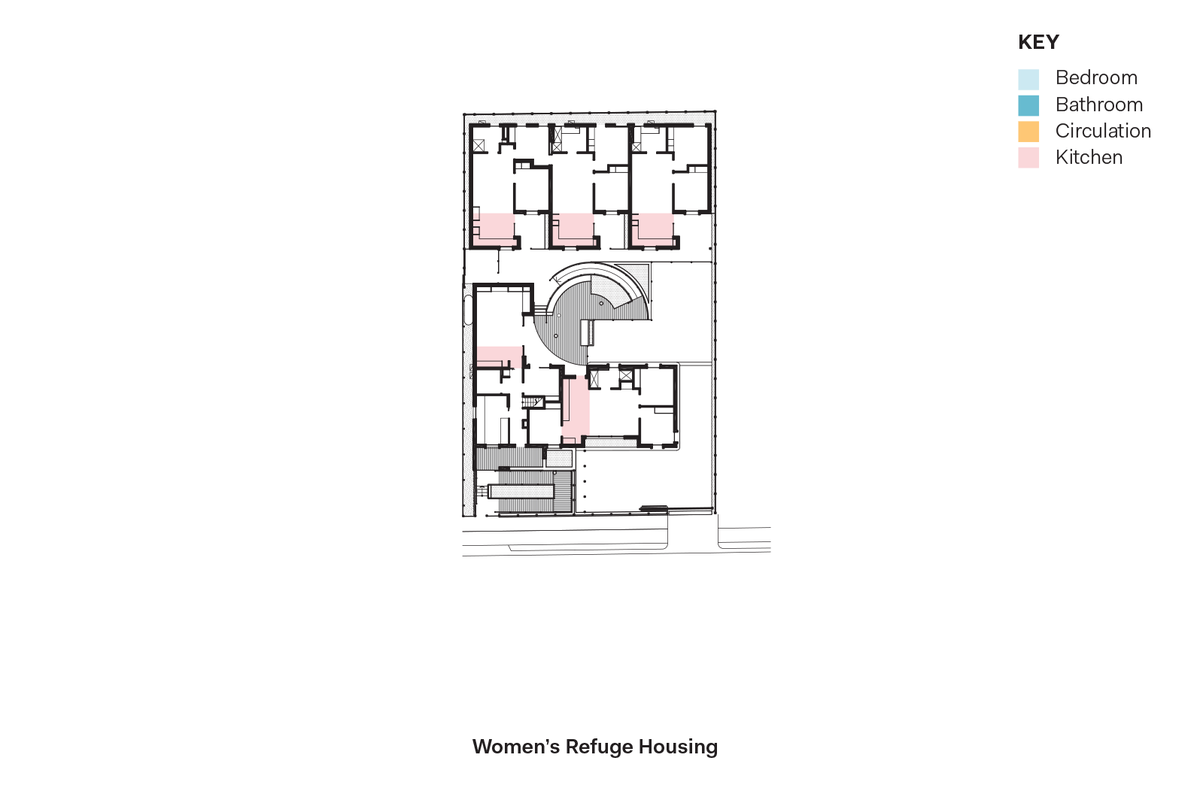

If landscape and ecology might be a means by which the private dwelling can contribute to the public realm in sensitive bush or coastal environments, how might the urban or suburban dwelling, in close proximity to neighbouring households and the street, enhance this interrelationship and build community? The placement of living areas – the more public part of the domestic program – adjacent to the street or to common gardens allows an exchange between private and public to take place, especially in the attached dwelling. In our experience, the kitchen in particular is a point of neighbourly exchange, especially when the individual house is part of a collective ensemble. This opportunity for visual connection between households is evident in our Women’s Refuge Housing (see figure 3) and Living Together Apart dwelling.

Figure 3: The kitchen placement in Women’s Refuge Housing allows for neighbourly exchange and visual connections between households.

Image: KTA

Size

Australia boasts the largest average house size in the world – around 240 square metres. The last of our surveys compared our various houses arranged according to size, ranging from 75 to 600 square meters, highlighting different people’s perceptions of what they “need” to live well. Strangely, empty-nester housing shows a trend towards upsizing rather than downsizing. Within the context of decreasing housing affordability and diversity, architecture can respond by developing new, more compact typologies and rethinking existing ones. The bloated single house could be converted to several and thus yield more dwellings within established suburbs and infrastructure. Empty-nesters could age in place but release some capital to fund extended retirement by selling/renting a portion to, say, a first-time home buyer or extended family. The lesson is to anticipate divisibility in the planning of future single houses.

Conclusion

“… the idea of possession is deeply rooted in us … possession is inextricably connected with action. To possess something we have to take possession. We have to make it part of ourselves, and it is therefore necessary to reach out for it. To possess something we have to take it in our hand, touch it, test it, put our stamp on it. Something becomes our possession because we make a sign on it, because we give it our name, or defile it, because it shows traces of our existence.” – N. John Habraken, Supports: an Alternative to Mass Housing, 1972.

In a recent article I advocated for architectural intelligence to be redirected from skin to bones in the multiresidential industry.7 The same goes for the single house: that we direct the bulk of architectural effort at the shell, the building’s parti as basic hardware, in line with Habraken’s theory of the “support structure.” Within the above scenario the architect could establish the fundamental moves – interior adjacencies, integration with site, neighbours and street – and relinquish control over the interior fitout. This task could be appropriated by the occupant, who, with DIY energy and enthusiasm, could customize and stamp the space with their identity. The architect could provide the house, allowing the actual performance of living to form home.8 There will always be a market for architect as ensemblier, especially in the high-end single house, but at the level of instrumentality within Australia’s housing industry, the contribution of typology – formative in relations within, around and beyond the house – is where architecture could become more relevant and much less expendable.

This article is based on the keynote address given by Kerstin Thompson for the Housing Futures symposium held in July 2015 by Architecture Media.

The 2016 Housing Futures conference will be held in Sydney on Friday 22 July. To view the program and purchase tickets, click here.

1. Rafael Moneo, “On Typology,” Oppositions 13, 1978.

2. Oliver Heckmann and Friederike Schneider (eds), Floor Plan Manual Housing , 4th edition (Birkhauser, 2011).

3. Shane Murray, “Medium density,” Architecture Australia , vol 91 no 2, Mar/Apr 2002, 50–55.

4. If we take a snapshot from the Australian Bureau of Statistics for construction activity in March 2015, 67 percent is residential. Of this, 53 percent is for new houses.

5. Alexander Klein’s Functional House for Frictionless Living, 1928, discussed in Robin Evans, “Figures, Doors and Passages,” 1978, in Robin Evans, Translations from Drawing to Building and Other Essays (Architectural Association, 2003).

6. Robin Evans, “Figures, Doors and Passages.” This distinction is beautifully described by Evans: “with the matrix of connected rooms, spaces tend to be defined and subsequently joined like the pieces of a quilt. Whilst with the compartmentalised plans the connections would be laid down as a basic structure to which spaces could then be attached like apples to a tree …”

7. Beyoncé or Barak: Is it a real choice? architectureau.com/articles/beyonce-or-barak-is-it-a-real-choice/

8. “House, a house, home: House is the abstract characteristic of spaces good to live in. House is the form, in the mind of wonder it should be there without shape or dimension. A house is a conditional interpretation of these spaces. This is design. In my opinion the greatness of the architect depends on her (his) powers of realization of that which is house, rather than her (his) design of a house which is a circumstantial act. Home is the house and the occupants. Home becomes different with each occupant.” Louis Kahn, “Form and Design” in Vincent Scully Jr, Louis I. Kahn (New York: George Braziller Inc, 1962), quoted in Yutaka Saito (ed), Louis I. Kahn Houses 1940–1974 (Toto, 2003).

Source

Discussion

Published online: 9 Jun 2016

Words:

Kerstin Thompson

Images:

KTA

Issue

Architecture Australia, January 2016