BETWEEN DOMESTIC SHED AND RURAL SHED, NMBW’S LATEST PROJECT IS A SUBTLE EXPLORATION OF EVERYDAY UTILITY, CONTEXT AND THE POSSIBLE ‘LIGHTNESS’ OF ARCHITECTURE.

The black “outdoor room” opening the building to the landscape.

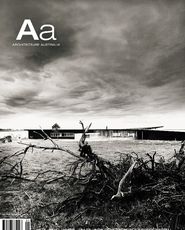

Seen from the approach drive, through the existing carport, the shed appears as another piece of rural infrastructure.

North elevation, with the outdoor room in its open configuration, showing the shed’s tight proximity to the existing house.

South elevation.

View from the south-west showing the shed in relation to the existing carport.

Views of the black outdoor room.

Views of the black outdoor room.

The white indoor room.

Looking along the verandahlike hallway, cut into the volume of the shed.

Stairs to the cellar.

The outdoor shower.

THE SOMERS “SHED” by NMBW is a reinterpretation of a well-known type, a familiar presence in the rural context in and for which it has been conceived. It is an extension to a house, although a separate building. A domestic shed often programmatically, or at least spatially, relieves the house. This particular shed gathers up and relieves the shortcomings of an existing house, to which it sits adjacent: providing an extra bedroom and bathroom, a non-programmed inhabitable mezzanine, a store, a wine store, a sheltered room-like open space, and a smaller open space physically connected to, yet spatially “away” from, both the new building and existing house. The qualities of these spaces are not domestic in nature or scale; they are characterized by a potentiality that is absolutely shed-like.

To think of this building only as an elegant shed, as one might for the work of many other “shed architects”, is to misunderstand NMBW’s approach to architecture. On this rural property, and throughout the area, there are many similar buildings scattered in that charged, informal way that is so difficult to get right and in fact is usually undesigned. This building becomes yet another element in this array, allowing the dignified house – a 1970s pavilion reminiscent of a Merchant Builders’ “Courtyard House” – to remain typologically “the house”. In this way, the project is a commitment to the context, rather than a self-referential work. It “disappears” in the landscape by means of its empathy and similarity with the existing ordinary and familiar architecture.

It is at once a confirmation of and challenge to its context. Yet, this architecture has a substantial volume and an accentuated scale as well. It is definitely there.

NMBW primarily work in the city. Most of their projects have been in or attached to existing buildings. In what must have been a confronting “walk-around” building, the siting of the Somers shed is tentative yet radical. Physically, the two buildings huddle together, resisting the endless possibilities of the rural site, and the pavilion that the building could have become. The over-scaling and proximity to the house provoke a paradoxical reading of the building: between domestic shed and rural shed, between shed for a house or house for a shed.

The strange closeness of the new building to the existing house sets up several critical scenarios and recalls the dynamic of the undesigned siting of buildings on farms.

It plays off an over-scaled carport to the east of the house and the larger sheds to the south-east. The hallway of the new shed is verandah-like and shifts between states of openness, connecting to the interior and outdoor open space. Future work will physically connect the house via a verandah, reaffirming the quality of the hallway and establishing the verandah of both house and shed as a “spine”. Currently, however, the separation makes for a potent reading that occurs through juxtaposition rather than physical linking, exaggerating the closeness.

The position of the new building redesigns the site so that what was once a long side/edge is now split into a distinct front and back. A front “yard” is created through the shed making a corner with the existing house on its north side. The back yard faces the distant swampland to the south. The back of the shed reaffirms itself when the large sliding doors to the “outdoor” space are closed. This space is room-like, with a low ceiling and roof, accentuating the site without framing it. These different and changing “outdoor” spaces are a rich offering of the project – the verandah-like hallway, the roofed outdoor space, and the exposed “edge” deck to the west. The west deck has a submerged spa allowing a dual programme. The deck opens and exposes itself to the edge of the property towards the swampland. It is a complete surprise that offers an incredibly different experience from the sheltered open space.

The shifts in scale and proportion – further manifested in the unifying of the interior volume as a white space and the outdoor room as a black space – are closely in tune with pop art’s approach to the reading and reappropriation of ordinary reality. Somehow, NMBW have always been interested in these ideas. In the past they have been more strongly available as graphic applications, here the exploration is subtler. Despite the absolute shed form, this is not a project that is interested in the symbolism of “being a shed”, but rather in the subsequent role it plays in the context.

The ever-so-slight bend in plan allows the building to relate to the house at one end and to the landscape at the other, bending to face away from the house and “out”. This critically distances the project from – although it is empathetic with – a Venturian approach. The bent plan prolongs the perception of the building and the landscape from within the building an essential moment longer. This is a sensibility that has been brought to the project, yet it absolutely belongs to and is manifested in the project.

The Somers shed does not draw attention; it is not an architecture that demands to be looked at with a sense of amazement. It is not a “new” and “innovative” architecture.

It is an architecture informed by the type of elegance that characterizes objects and products which are simple and familiar, and therefore are unobtrusive and discreet in their (un)appearance.

A simplistic relationship between architecture and landscape is further resisted in the way that this building does not intend to frame the landscape or to capture the view.

This shed becomes part of the landscape by opening itself to it and, at the same time, almost naturally accepting/absorbing it. Unlike the south side, the north side does not even provide a physical separation between outdoor and indoor. They are indistinctly interrelated and overlaid in the Heideggerian sense: reciprocally “belonging together”.

This is an architecture that is capable of resisting the Modernist – both colonialist and capitalist – process of conquering and seizing the landscape by framing it within a view.

It is also interested in a state of being closed and open, aligned to the dark and light that are reversed (black room outside, white room inside). The interiors are quite closed, there is no attempt to “bring the nature inside” – a reminder of the potency of insideness and closedness that is lost in much contemporary architecture.

This project is a contemporary Australian example of a more and more diffused design approach which, as poignantly observed by Pierluigi Nicolin, operates “in a wholly pragmatic way, without any fuss, a light and disenchanted approach to the job of architecture… This is the fruit of a fairly widespread effort, principally on the part of young architects intent on carrying out small-scale interventions at low cost in which a great deal of hard work is put into the design.”1 ›› This architecture resists abstraction and easy/seductive minimalism, yet at the same time it is very minimal, somehow “dumb” in concept: it is “just” a shed, another shed – although slightly and critically different from those in its context.

LOUISE WRIGHT AND MAURO BARACCO ARE PRINCIPALS OF BARACCO+WRIGHT ARCHITECTS. THEY TEACH AND RESEARCH AT RMIT UNIVERSITY, WHERE MAURO IS A SENIOR LECTURER IN ARCHITECTURE AND LOUISE IS A PHD CANDIDATE.