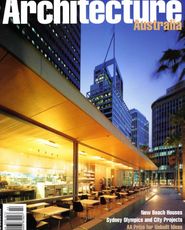

top Looking west, with the northern decks at right. above Looking south-west from the northern deck. Click to see enlarged photo.

Screens on the east side of the house.

The studio on the west side of the house.

| Project Description

Mooloomba House is a two-storey holiday house built in the beach community at

Point Lookout on North Stradbroke Island off the south-east Queensland coast.

The main wing, located to the west of the site, comprises a narrow, two-level

gallery. This linear element links two rooms separated by a small courtyard on the

west side and overlooks the main courtyard, filled with mature banksias, on the

east. The north facade overlooks the ocean.

Architect’s Statement by Peter O’Gorman and Brit Andresen

The house has two key intentions: fix its location in the landscape by constructing

as much as possible of its small (500 sq m) site as outdoor rooms, and continue

exploring the use of local hardwoods in domestic buildings in Queensland.

The search is for the expressive capacity of hardwoods, derived from material

properties, geometries and metaphors.

The use of hardwoods as part of stud-framed systems to hide the defective

behaviour of the frame (those well-known characteristics of hardwoods to warp,

twist, cup and crack as they dry after milling) has always seemed an unfortunate

loss of an architectural opportunity in a material where high strength/durability does

permit external use and the potential for contribution to building expression.

In Mooloomba House, the simple strategy used to tame these expressive lateral

movements is to vertically laminate thin members of opposing grain and integrate a

1200 mm panel of 18 mm waterproof ply sandwiched between. The frame acts as

enlarged ‘cover battens’ to the joints in sheets. The technique also facilitates a

prefabrication process.

Having drawn the frame into an expressive role in the building, three important

ideas inform the underlying architectural intent for the house.

Firstly, in her 1988 essay, ‘Proportioning Systems and the Timber Frame’ [ Parabola

No. 13), Rachel Fletcher explained that before Homer, the ancient Greek word for

harmony, harmonica, was a carpentry term meaning “a timber frame such that to

take away one piece would collapse it”; ie the components must fit together

harmonically to make a whole. In Mooloomba House, the generative 2000 x

1200mm (1:1.618) proportion of the expressed panel and primary frame is intended

to appropriate this ancient meaning to the poetic interpretation of a mathematical

proportioning system producing visual integrity. In these days of environmental

crisis, the ancient architects’ belief that Nature and the entire ‘spherical’ universe is

a living harmonic whole does not seem an inappropriate reference. To recognise the

humble timber frame as the genius of such a profound sequence of thought is to

expose its architectural potential.

The second idea is that space may be characterised as different places by different

constructional form; eg Tectonic Space, made by the assemblage of relatively thin

pieces (the bower) or Stereotonic Space, created as if carved out of mass (the cave,

etc). The thought in this very small, (60 sq m) house was to explore the inclusion of

three different constructional forms (all hardwood) in three different segments of

the building held together in forms of what Aldo van Eyck calls “reciprocity”.

The third intention made possible by the benign climate of Stradbroke Island is the

opportunities for ‘transparencies’ with the tectonic form of creating space. Such

opportunities begin to bridge technology (material and technique), light, territoriality

(the plan) and relationship to the landscape, and also recognised an opportunity for

what Colin Rowe has termed “phenomenological transparency”, where several

conditions may be layered together.

|

Comment by Peter Tonkin

Peter O’Gorman and Brit Andresen’s house has a very real fascination, both sensually and intellectually. Architects’ own houses illustrate their preoccupations without the input of a client’s taste, and beach houses, in their casual acceptance of BBQs and sand, offer an escape from the demands of daily life. The Stradbroke Island house capitalises on these freedoms to become a special kind of case study-the distillation of a set of challenging architectural principles, carried out with style and economy, at no time losing the essence of the beach retreat.

O’Gorman constructed the house with a boat-builder and a third helper, and spent much time perfecting the use of timber to reduce waste and cost. This delicate economy is partly the result of the one-hour trip needed to ferry all the materials across Moreton Bay from Brisbane.

The result-as complete as the houses architects build for themselves ever are- has none of the bricoleur’s shortcuts or make-do; the care taken with its design and construction communicated eloquently by the delicately woven and perfectly mitred timbers of the balustrades and by the smell of the eucalyptus oil preservative which hangs in the coastal air.

Without conceit or even much apparent effort, the house intimately blends the intellectual rigour of the ‘Ideal Villa’ with the casual rusticity of the Queensland vernacular, to create a habitable landscape in one of Australia’s loveliest settings. It is almost the antithesis of a suburban cottage. Movement paths are curious and often indirect, opening views of the landscape and often requiring the occupant to go outside the enclosure of the walls to reach another room. Its accommodation is spartan in size and finish, but possesses a generosity of spirit and a richness of architectural inventiveness which make the house truly luxurious.

The parti is straightforward: the union of a long narrow wing to the east with a row of three box-like pavilions. Two of these are enclosed as living areas, whilst the middle is partly open as a sandy courtyard. The long wing, housing the kitchen and the upper-level sleeping cubicles, is a syncopated construction of thin timbers and stressed-sheet panels, building up layers of enclosure and frame to a strict and functional module which achieves a Katsura-like elegance. The pavilions, in contrast, are rustic in their architecture, supported on unhewn tree trunks.

All of it responds to the very benign climate of Straddie-never really cold-and with every breeze welcome in summer. Deep overhangs and lots of roof insulation keep the lightweight interior cool-the development of one of Australia’s most characteristic vernaculars.

The long east wing dominates the perception of the house, forming both of its visible facades and accommodating the major circulation. Its mathematical sophistication follows a developmental path from classical geometry via Palladio, through Japan to Corb and the module-obsessed 60s work of Brutalists such as the Smithsons. Here, as then, the justification is the minimalisation of material use; the results offering a genuine reduction in waste and the exploitation of the structural capabilities of the smallest pieces of timber. But O’Gorman and Andresen have achieved a lightness of touch and a sensuality of light and shade which transcends intellectual rationality.

In contrast to the modular timber Meccano of the east wing, the three box pavilions, with their forest supports and roofs braced by frames which recall gable trusses, are allusions to the primitive hut. The living room is the closest the house gets to a conventional interior, with its focal fireplace and plasterboard lining, whilst the open court recalls the deliberate rusticity of the Japanese tea house. Here the battened timberwork is highly considered but seems random and the translucent ceiling sheds a soft light. These two types of build form interlock both spacially and structurally at each place they meet; increasing the complexity of a tiny house and ensuring that there is no sense of a simple, Kahn-inspired, servant-served duality to the spaces.

The scale of the building is constantly deceptive. The hovering ‘front’ aedicule is narrow, even tiny, whilst the long eastern wall seems to be part of a very large house indeed, making the garden a huge outdoor room.

Inside, the “bed boxes” are as small as practical, and the larger living spaces are generous only because of their openness to the landscape. The complexity and variety of the circulation and this ‘borrowed’ landscape achieves a palpable enlargement of the whole, making a house of less than 70 square metres internal area seem double the size.

This again is a revision of the contemporary suburban bungalow, where repetitive, enclosed cubes of spaces make even large houses swiftly comprehended and lacking in mystery. With its belvedere seeming to hang in the treetops, inviting in both the breeze and the ocean, the house is essentially a landscape pavilion, closer to a Japanese moon-viewing platform than a suburban cottage. The geometry is rich and complex, used without ostentation to render inhabitable a lovely landscape.

Rooted in some of the most interesting and sophisticated of the traditions of the world’s architecture, yet specific to its time and place, it is a house which is complex and challenging but relaxed and seemingly simple. It seems, for all its internationality, completely Australian.

Peter Tonkin is a principal of Tonkin Zulaikha in Sydney. Mooloomba House, Stradbroke Island, Queensland

Architects Peter O’Gorman and Brit Andresen. Structural Engineer John Batterham Leadlighting Peter Nelson Builders Peter O’Gorman and Graham Mellor.

|