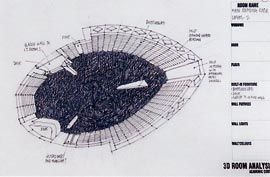

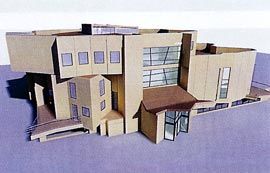

The new Academic Centre for Newman and St Mary’s Colleges, the University of Melbourne, by Edmond and Corrigan.

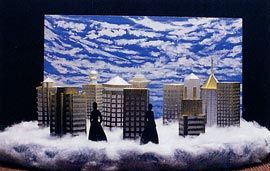

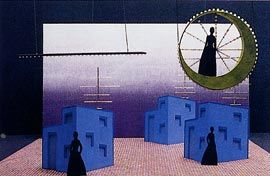

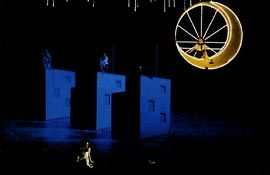

Images showing the design and realised set for Le Grande Macabre for the Komische Oper, Berlin, by Peter Corrigan.

There is nothing more galling than the would-be sage who rises to his feet and, with twenty-twenty hindsight, proceeds to glamorize some previous era and demonize the present.

Architecture – aside from the customary Roman demands for delight, commodity, instruction, utility and whatever – should “minister” to our sense of self worth, our sense of identity. I am a Melbourne architect, inclined to think architecture is a local matter. Probably xenophobic, but with a small x.

In preparation for this evening I read a dozen of the recent A. S. Hook orations with some care. They can be obtained from the RAIA website.A pattern emerged and certain concerns of the last decade of the twentieth century caught my attention. I thought it might be of some use to make a few comments off the back of that reading.

The teaching of architecture has been criticized over the last decade with much talk about the crying need for practitioners in the studios. This demand I believe has been met.

Glenn Murcutt (1992), in particular, was rather tough on tenured teachers in architecture departments. My own experience at RMIT suggests that the teaching staff (including the few struggling tenured members) are a committed group like Japanese Australian Rules footballers – they are hard at it and give 140 percent of themselves, while dealing with an onerous administrative load, and continual budgetary threats.

As an example, I would cite Mr Doug Evans at RMIT, who has managed to accommodate change over the years but has never lost his sense of purpose or his basic faith in the teaching of students. His recent elevation to the position of associate professor is a plume in the cap of the administration. And I would, also like to, congratulate the University of Melbourne for filling not one but two professional chairs from within its own ranks, with the appointment of Dr Philip Goad and Dr Kim Dovey.

What has occasionally been missing in university architecture departments is leadership. Professorial chairs have languished or departments have disappeared into multidisciplinary quangos, where the chequebooks are in the hands of building scientists or geographers. The Institute might like to consider the professional cost of this lack of leadership.

While I’m probably not the best person to comment, politics was alluded to in a number of orations and Don Bailey (1991) wrote with insight and enthusiasm on this topic. In the more opaque or silky orations, it was conspicuous by its absence.

Nowadays, it is quite apparent that the Rum Corps and its media cohort again avidly run the country (if they have ever ceased to), but it is my impression that the national Institute, based in the dormitory suburb of Canberra, does see a federal mission for itself. The former National President Graham Jahn, in particular, has driven this pluralist mission. He put the pastoral above the political (Pope John XXIII i.e. 23rd). I thank Graham for his efforts, and mourn the passing of Professor Peter Johnson, a particularly adept politician who was generous to our office and made an enormous contribution to the profession.

The Institute is certainly doing its best within the present-day building industry ecosystem (consisting as it does of whinging, project management, liability insurance, ramshackle or contingent politics etc). And we should recognize and commend the their states of NSW and Queensland (and soon Western Australia) for the installation of State Government architects (Chris Johnson and Michael Keniger). The new State Conservatorium of Music in the heart of Sydney and the South Bank Arts Precinct in Brisbane are examples of how a state architect can make immense cultural contribution to a city’s fabric. Closer to home, the State Government of Victoria believes that a Design Excellence Initiative is an attractive policy, but it has failed to understand that the position of State Architect should highlight such an initiative. The first State Architect in Victoria was William Wardell (1860), the student of Augustus Pugin and the designer of St Patrick’s Cathedral. Oddly enough, the last State Architect was Maggie Edmond.

Simplicity was mentioned sufficiently often to annoy me. I will never forget hearing as a youth, one of Mies van der Rohe’s mantras at a student party “St Thomas Aquinas says, reason is the first principle of all human action. If you understand this you act accordingly.” This selfserving truism retains its relevance, but more probably the truth lies closer to Goya’s “the dream of reason bring forth monsters”. Or more simply, that the law of unintended consequences usually applies and asymmetry gives force to own recognition.

This idea of simplicity may have something to do with widespread concerns during the last decade about the lack of architectural involvement in suburban tract housing. Is there any public housing left? Well, in Victoria, very little.

This lament for the design of the suburban house was a common motif in the orations. It brought back memories of the fastidious and energetic Robin Boyd, in an earlier time, leading the charge on housing standards. I quote this paragraph from Peter McIntyre’s (1990) oration.

“Boyd wrote every week in The Age. I worked with Boyd to produce Cross Sections which was mailed to every building industry group throughout the country. I was teaching final year at the Architect’s Atelier. I worked with Boyd on the Sunshine House at the Ideal Home Exhibition and we created queues stretching from the inside of the Exhibition building to outside the entrance doors, and on the street. I combined with Boyd to make the film, Your House and Mine. Television had arrived in 1956 and we even devised a machine for animated graphics for Crawford Productions.

“In the meantime I joined the Chapter Council with Boyd and became President. We were determined to stop the tide of rash development. The Architectural Orations were organized with a series of overseas speakers. The papers were published and there was much publicity. Melbourne was to be the site for the next RAIA Convention. This convention had been formalized into a certain pattern for tax deductions: It was to be one big working party.

We approached Minister Hamer and undertook preparations of a Planning Scheme for the satellite city of Sunbury. This was to be the final example of everything that we believed in. Boyd wanted the city designed right down to the Swedish knives and forks.We worked day and night for twelve months. He died on a Friday night. The Convention began the next morning.” ›› While this makes very moving reading, Boyd’s sudden death hardly seems a surprise and Peter McIntyre was a bit stiff. Still, neither he nor Boyd could be faulted in terms of energy or endeavour. The housing industry, however, rather like speculative high-rise development continues to march to the tune of its own market force imperatives.

The suburbs still attracted disapproval. In political terms they are always a nuisance when State Governments run low on infrastructure funding. In Victoria legislation is on the books to turn back the ever-widening suburbs, King Canute style, and redirect the population toward the inner suburbs and townhouses. The suburban dwelling for the traditional Liberal voting moral middle class should be simply viewed as an indigenous housing type, and we might reflect upon R. G. Menzies’ vision of a lemon tree and a cricket pitch in every rear yard. The issue for young homeowners, Menzie’s forgotten people, is the ownership of the land. (R.G. Menzies was still Prime Minister of Australia at the age of 74. I’ve occasionally wondered whether Mr Howard dwells on this fact.)

Last year, the Australian National University economist Simon Kelly projected present trends into the future. By 2020, he estimates, barely twenty percent of people in their early thirties will own their own home, a massive change from more than fifty percent now. Banks and credit cards, our leisure society and lust for instant gratification, will achieve what the politicians can’t legislate: the death of the Australian dream of home ownership for Mr Howard’s battlers.

Most medal winners were unhappy, also, with the city. Petrol-guzzling cars, over crowding, hostile streets and so on and so on.

A litany of negatives when the later half of the twentieth century rebuilt more cities than the previous nineteen centuries combined.

It was most surprising to find throughout these lectures no reference to the public pleasure of experiencing architecture. Instead, the “difficulty” of the cities weighed heavily on the lectures. Too little planning control or too much planning control, there appeared to be little in the way of middle ground. Australian cities are, in reality, a success story and compare favourably with similar models in the USA as good examples of thriving New World centres.

They should be recognized for what they are.

Of course they are one-dimensional and are not places where life can be lived at its fullest intensity; they do not have anything extraordinary to tell the country, let alone the larger world beyond. This should hardly surprise us.

A recent visitor described Sydney, however, as “a world style city par excellence” and I have an acquaintance there who used to sing Portuguese love songs in a restaurant in Double Bay.

Certainly, the mark of a mature city is the breadth of its musical culture.

Another popular theme, the team player garnered overwhelming support while his or her nemesis, the ego maniac was to be avoided at any cost. This caught me off guard as this language is usually associated with the belittlers and begrudgers who are endemic in Australian society. In some respects the public image of the team player has cost us dearly. Society is often not quite sure what it is architects do; what full services mean or what they should cost (see erosion and perceived consultants). The team player has always reflected our mistrust of the singular life, or the perceived revisionism of monastic orders or the political incorrectness of zoos with cages.

As opposed to this opinion I would commend the local contribution made by Peter Davidson and Don Bates, not only for their distinguished Federation Square project but, also, for their very public presence as its very public design architects.

The American architect Robert Venturi observed some years ago that architects should get back to designing buildings well. Building them is the team exercise. To highlight the preeminence of design, the Institute – at both state and national levels – might try to promote legible competition packages or programmes for public buildings, to generate work opportunities and illustrate to municipal officers and the public in general, what architects do best.

Ken Woolley (1993) spoke eloquently on the topic of the “Architect as Artist”. The postmodern has often been an art of emergency. It has been driven by formal experimentation more often than by ideology. Many good buildings have been built for the wrong reasons, but there is also no doubt that great buildings are ideological (that is political) by their nature.

Contemporary art has often acted as form of honourable resistance; sounding alarms about the world we’ve been living in for decades and occasionally talking up the superior nature of art; and often nurturing the hope that a socially marginal architecture might be celebrated by the mainstream. This vain wish that society (read planning departments) will thank us for designing “different” or “non conformist “, even “unwelcome” buildings often leads to disappointment and frustration. The reality of 2003 is that today the sense of the possibilities of art has been diminished. Absinthe and tattered clothes are no longer the attributes of the new.

To my surprise, the failings of Modernity are still a topic for dispute. These failings apparently impact upon all of the prior issues. If the Australian present (2003) looks a lot more like 1953 than 1953 looked like 1903, this suggests that the rate of change driven by the digital and virtual technology has not been as great as was predicted or hoped for. The human scheme of things, or shall we say, more modestly, the design of buildings, may not have advanced quite that much since the world of Sigmund Freud and Adolf Loos. Recently in Vienna a taxi driver observed to me as we passed the Parliament House, that had been built by the Emperor (in 1905), “Ah, the Hapsburgs. They cast a long shadow.” ›› Today we may pay maternity leave, at least Mr Howard says it’s on the table, but the eighthour- day monument (built in 1903) and commemorating an event that occurred in years earlier, still stands at the corner of Russell and Victoria Street. History lives or dies in its buildings, and while history is now being unmade, our own times might be appreciated for their continuities as much as for the pace of change that is apparent.

This award requires that we thank our clients over the years. In no particular order I would like to thank Fr Barry Moran, Mr Alan and Mrs Lois Lewis, Mr Robert and Mrs Melissa Lehrer, Mr Frank and Mrs Kathline Mercovith, Mr Louis and Mrs Sophie Athan, and the MFB.

My partner, Maggie Edmond, should be recognized and publicly thanked. There is a great deal of prurient curiosity surrounding our partnership. It is really nobody’s business; but the following anecdote may be informative.

When she was a schoolgirl at St Leonards, where she was dux of the school, Maggie occasionally told teachers the wrong answer to questions on purpose, because that appeared to make them more relaxed. I’ve always liked that story, as oddly enough at the time I was in the back row at the Christian Brothers College in St Kilda in a dazed state.

The ticket price of this lecture is such that I feel obliged to show some work. These are two projects that have run parallel in the office for two and a half years. One was a hobby the other is deadly serious: the design for Le Grande Macabre for the Komische Oper, Berlin; and the Academic Centre for Newman and St Mary’s Colleges at the University of Melbourne.

To conclude: architecture should enhance that sense of a defining difference. Which is central to what makes a culture rich and its citizens proud.

Architecture is the thing with feathers.

Peter Corrigan

This lecture was delivered at Storey Hall, RMIT, on 29 August, 2003.

10 LESSONS FROM CORRIGAN

A tribute from Ian McDougall on the occasion of the A. S. Hook Address.

The work of Peter and Maggie is an enduring menagerie of startling and raw expression. The projects are inspiring in their refusal to concede that architecture is just vanity, or glib seduction. To those who wish to learn, they are didactic, reinterpreting some architectural maxim. In preparing for tonight, I found myself speculating on what it was that I or we had learnt from Peter. Tonight there are ten lessons, written more on the napkin from the La Casalinga than in stone, more like banner heads from the Herald Sun than commandments.

Lesson 1. Local recollections make good architecture. If there is one life-changing realization in Edmond and Corrigan’s work, it is that the projects contain glimpses into the Australian city. The idea that art could be made out of the raw material of our own backyard, out of the madness and stories of people we know, remains one of the great lessons for us as architects. It is reflected not only in the buildings – the Melbourne City Square as footy oval, the Belconnen Youth Centre as picture theatre – but also in the writings, the reviews, the theatre work and the sponsoring of work of others. To many of us with a strange love of things local, these intelligent/learned and courageous works were liberating, they pointed a direction that could become something to live your life for. They taught us that even if the material was rejected by the rest of the world it was ours.

Lesson 2. Learning thru talking (carousing). For a decade, a group of us would meet on a Wednesday night, after teaching at RMIT, at the Casalinga, Maria’s et cetera to argue, to discuss architecture and its meaning. This would go long into the night, and while argument ensued, these discussions were for the most part, friendly affairs. Peter was a regular and generous participant. Here we learnt that such discourse is the stuff of a local culture. In this atmosphere, a few of us began Half-Time Club, and a few of us started Transition. Peter’s assistance in these eruptions must be acknowledged. The lesson has continued – through Pataphysics and Backlogue to Subaud, through Half- Time. These have created a local architectural culture that can be articulate, self-critical and yet cohesive.

Lesson 3. Books are better than cars. After lunch with Peter, it is always necessary to return to his office for a special coffee and to sit in his private library and marvel at the breadth of ideas that lines the walls: to luxuriate in the illustrations, the rare architectural books and bound periodicals. Forget the smooth vehicle, go for the library. These books manifest Peter’s continuing interest in the history of architecture, cultural history and ideas.

Not an academic, nor a mere observer of architectural culture, he is a maker of that culture. Here is a link with the learned tradition of American academe, with the local bush intelligence of Annear and Hunt, and with a thin line of radical intellectualism that flowered after WW 2 in the union movement. This line of rough practical radicalism, which in Peter springs from the Carlton Theatre Push, offers a role model for those with an interest in architecture as a cultural and sophic activity. Peter’s library symbolizes this possibility.

Lesson 4. Ugly it ain’t. Peter’s engagement with the difficult and the grotesque is a path few tread. Projects like the Dandenong TAFE and the Kay Street Housing veer in and out of focus, looking clumsy and malformed.

But this is a superficial reaction – the buildings are funny in a good way, they are forceful, personable, memorable. This character is enduring. It taps into a line in German Romanticist theory that recognized what Schlegel referred to as the “limitations of the Beautiful”. E&C’s work refuses to fall into an easy seduction through flattering conventions of materiality or shape. It pursues the familiar and generic, transmogrified into dynamic, strident, agglomerated iconography. It questions the bland aphorisms of beauty and raises the difficult issues of purity and exclusivity. For me, this lesson is also about intellectual endurance and resisting the seduction of one’s eye. It is a lesson well learnt by Melbourne architects.

Lesson 5. The world is not black white and stainless steel. The layman, I am told, loves the Swanston Street facade of Building 8. But E&C buildings will always get a rise from sections of the profession – usually in terms of colour. The recent reaction to the Victorian College for the Arts Drama School, with its pink and golden Showboat exterior, shows that Peter is the most skillful (albeit outrageous) colourist. Unlike other recent attempts at colour in office building facades, the work of E&C teaches us that pure colour is a powerful architectural tool. Its capacity to unnerve or to glorify cannot be denied. The colour work is masterful and his success has seduced lesser architects into its use. But from such bravado we learn that to not use colour, to sag into the vacuousness of the integrity or nobility of plush materials, is to ignore a whole architectural dimension.

Lesson 6. Teaching makes a culture. In Melbourne, any young architect worth his salt must do some teaching in a design studio. When Peter returned from the US in 1974 and joined the staff at RMIT, he was part of this tradition. However, he took teaching in new directions.

Vivian Mitsogianni has identified the key aspects of Peter’s teaching – the exposure to a wider cultural field, the enforced engagement with non-architectural material, the teaching of subjective judgment. This is learning in the round, participatory and sometimes ruthless. Over a long period, Peter has taught us that it is necessary for architects to teach, to engage with the intellectual hot-house that is the school. Equally he showed how important it is for students to have contact with teaching practitioners. Both lead to a culture that is in touch with its consciousness and yet retains a pragmatic utilitarianism. Complex ideas can be built.

Rich buildings can be analyzed. Peter’s generosity in this area has taught us that architectural culture, while lacerating itself over the next commission, can also still have a sense of cohesion and mutual respect.

Lesson 7. America does not necessarily advance in your career. Strong teachers generate strong pupils. Not all lessons are learnt through agreement. A few of us disagree with Peter’s support for the US. His own experience and liberation through studying at Yale has lead to support for those who wished to study there.

The argument against this is twofold. Firstly, it strips local culture of smart students and their possible energy in researching and documenting local culture.

Secondly the experience for those who go is often so overwhelming or distracting that they never return.

Or, if they do, they have great difficulty settling back into the petty humdrum life that is architectural practice. I saw some of the best minds of my generation destroyed by overseas study!

Lesson 8. More ideas, less refinement. In lecture last year, Peter expressed disillusionment with his faith in the US. The lecture was one of his best. He re-presented his talk at Yale in 2001, and simultaneously provided a commentary on the American students’ reactions to this work. The failure of the privileged students at the centre of the world to engage with the work, to even fain interest in the issues raised was, for Peter, disrespectful and bigoted. There are few timber battens in his work. There is very little curved corrugated steel, and if there is some it is not surrounded by gum trees.

It is hard work, with a dense texture and richness that is unfamiliar to young ambitious eyes. In that lecture, Peter made a pertinent rallying call to all who had forgotten the reason for architectural thought. It was a call against lapsing into lazy habits, a call to undertake courageous trajectories and to not be diverted into the dinner party conversation of what a struggle it is to build. It pricked many a conscience, a reminder of how we missed Peter’s advice.

Lesson 9. Hard work never hurt anyone. Between 1977 and 1979, while still a student, I spent a series of sleepless nights making sets and collecting properties for shows such as Back to Bourke Street, Rockola and Hancock’s Last Half Hour. I came into contact with a life that was about applying one’s full energy and life force into getting the job done. And these incidences were about architecture, working with a real architect, who coerced and anxious-ed us into getting the right design result. It was done from drawings, but if it looked wrong as it was built it was changed. This is the lesson of how much effort it takes to get a worthy result. And that there is no end to it.

Lesson 10. In the everyday is the political. Architecture is highly political – its very delivery is sustained by business and industry, but also political in its historical power and because its audience is the general public.

Many of Peter’s lectures include a slide of one of football’s greatest players, the complex wizard Nicky Winmar. The St Kilda wingman and follower, who, in May of 1993, after the racial yells of some rabid Collingwood supporters, lifted his Guernsey and yelled back I’m black and I’m proud of to be black. Peter’s use of such images of mass culture, of significant events that cross ideological and populist themes, reminds us that wes must engage with the community in which we operate. In each act of advocacy, of design, of critique, of whatever we did, there is a political dimension and that must be explicit.

These lessons have created an atmosphere in which architects now expect open criticism of their work and, in spite of this, pursue their work with courage and thoughtfulness. This, in turn, has made a city that commissions the most adventurous architecture in the country. I retreat from using the term “world class”, since Peter’s friend Barry Kosky damned the term, but the city has achieved an international standing as a design centre. Peter has led this cultural maturation.

He has been generous, being the only practitioner I have seen who, in talking about his work, includes examples and spin of other colleagues:Wood Marsh, Norman Day, Keith Streames. And above all, he has inspired us through his life and his work to act with the greatest courage in our work, in the face of indifference and mediocrity.

Thank you Peter for teaching us these things.

Source

Archive

Published online: 1 Nov 2003

Words:

Peter Corrigan

Issue

Architecture Australia, November 2003