The history of Troppo Architects begins with an apocryphal story, retold recently over a lively lunch in Perth’s foothills. Sitting around the table in a Troppo-designed rammed-earth house – mine, as it happens – are Adrian Welke and Phil Harris.

We reminisce about our youthful Darwin days, circa 1980s, when they were hyperactive budding architects and I was an earnest cub reporter in the ABC office.

They are little changed from the day we first met: iconoclastic blokes with wry humour and unbridled energy. And the story we are revisiting is typically irreverent – how they thumbed their noses at Darwin’s architect cognoscenti when they sought to register Troppo as their business name.

That two twenty-something upstarts from “down south” should adopt such an unbecoming name – a vernacular term for going stir-crazy in the tropical heat – incensed the conservative rump. What was wrong, they demanded to know, with the time-honoured tradition of using surnames?

“There was a complaint made to the registration board and luckily a lawyer friend of ours got the file,” recalls Welke. “She told us nothing in the rules prevented us from calling ourselves whatever we liked. Our fallback position was that we would have gone down to the deeds office and changed our names to Phil Troppo and Adrian Troppo. My mum was really happy it didn’t come to that.”

The anecdote is classic Troppo, an act of playful anarchy with a serious underlying logic. They wanted an open-ended name that would lend an inclusive and collegial feel to the practice – like-minded people could then step in and out of the Troppo circle. And, in the intervening thirty-five years, they have.

But it is Welke and Harris, as Troppo Architects’ progenitors, who are the recipients of the Institute of Architects’ 2014 Gold Medal. They are keen for me to recount our conversation “without using architecture-speak,” although Harris can philosophize eloquently about his design ideals. Welke constructs sentences as spare and nuts-and-bolts as the buildings Troppo has created.

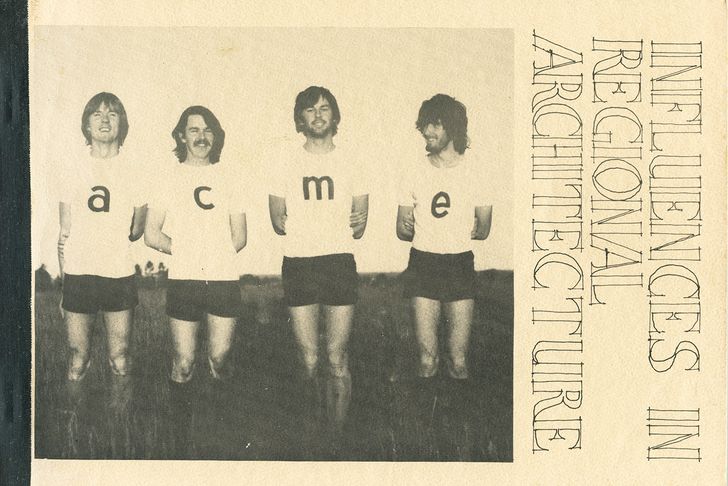

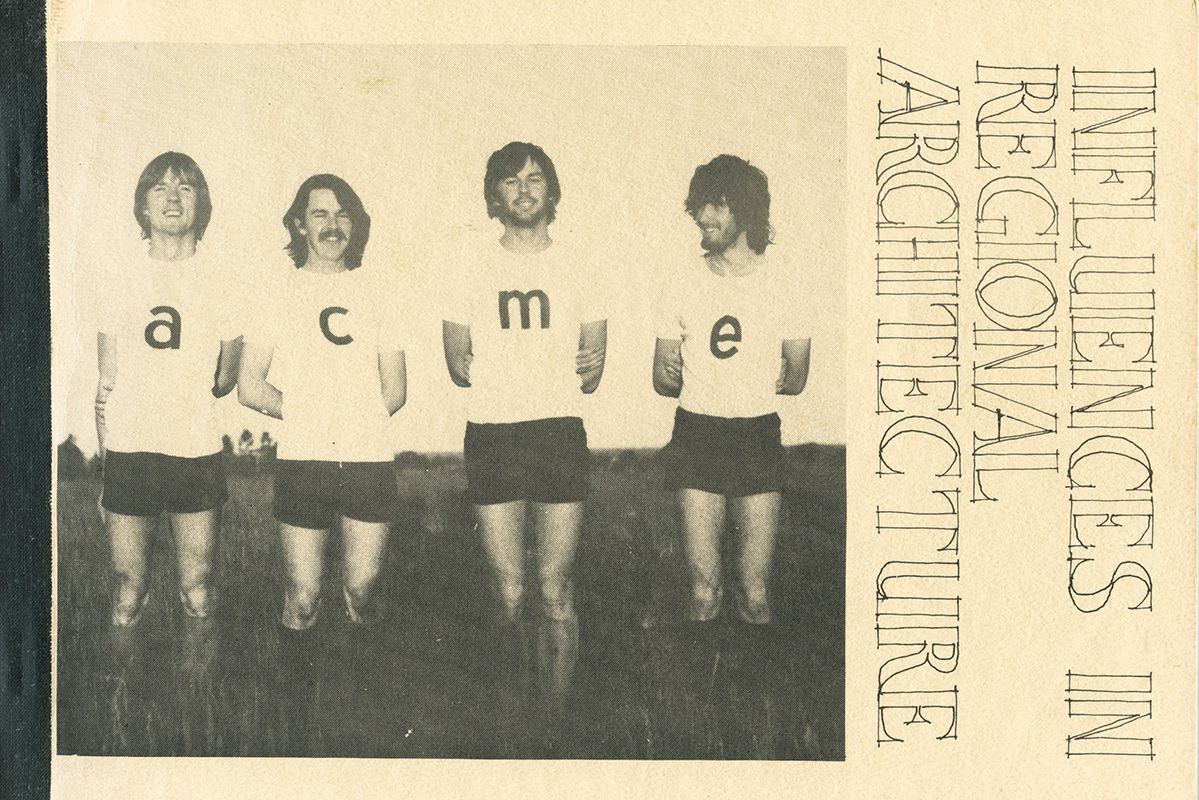

Influences in Regional Architecture showing (L–R): Adrian Welke, Justin Hill, James Hayter and Phil Harris. Published May 1978.

We start our conversation with the Troppo pilgrimage of 1978, when Welke, Harris and University of Adelaide co-students Justin Hill and James Hayter piled into a clapped-out Kombi van and headed out on a study tour of Australia’s regional architecture.

“We were struck by the abstract nature of pearling masters’ houses in Broome, with no windows and an open floor plan,” says Harris. In Darwin, they were drawn to airy, elevated public servants’ houses – most built in the 1950s – that met the challenge of extreme humidity in the wet season and fierce heat in the dry.

“I don’t think we could have comprehended how little architecture people lived with up north,” Harris says. “By that I mean what constituted ‘shelter’ and how relaxed and informal that shelter could be. How it wasn’t important what it looked like, it was a device for getting on with living. It was almost a shocking discovery for a boy like me from Adelaide.”

As new graduates, the duo struggled to find jobs in a recession-hit economy. Harris took unpaid work in an Adelaide architectural firm, while Welke went home to the family farm near Esperance in Western Australia before heading to Darwin in 1979 to work in the Department of Transport and Works.

Welke’s brief flirtation with bureaucracy segued into a job with Vin Keneally, a genial Darwin architect whose practice was thriving in a commonwealth-funded era of infrastructure building. Welke spread the word among fellow graduates and Harris and Hill jumped on the next plane.

We reminisce about 1980s Darwin as the perfect place for young professionals – from altruistic architects to aspiring journalists. Self-government had inspired an optimistic, open-minded embrace of new ways of doing things.

“Residents felt a sense of euphoria about what we were and where we were going, and we fell into the opportunity,” says Welke. “Darwin is historically full of small developers, people from all backgrounds shaping the city. We joined in that ‘have-a-go’ attitude.”

They were helped by the fact that project home builders were absent in post-cyclone Darwin. And the government’s “solution” – airtight houses as solid as concrete bunkers – was proving wholly unsuited to the climate.

“People understood that we offered something better than what the Darwin Reconstruction Commission was offering,” says Welke. “It wasn’t hard to put up our hands and say ‘we’ve got an idea.’”

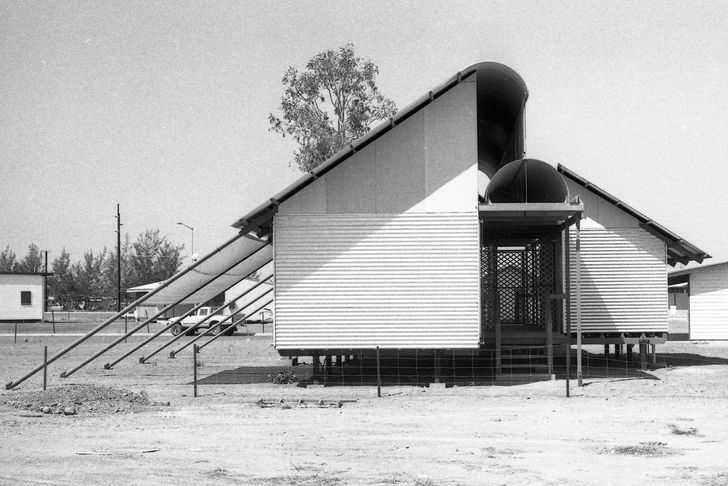

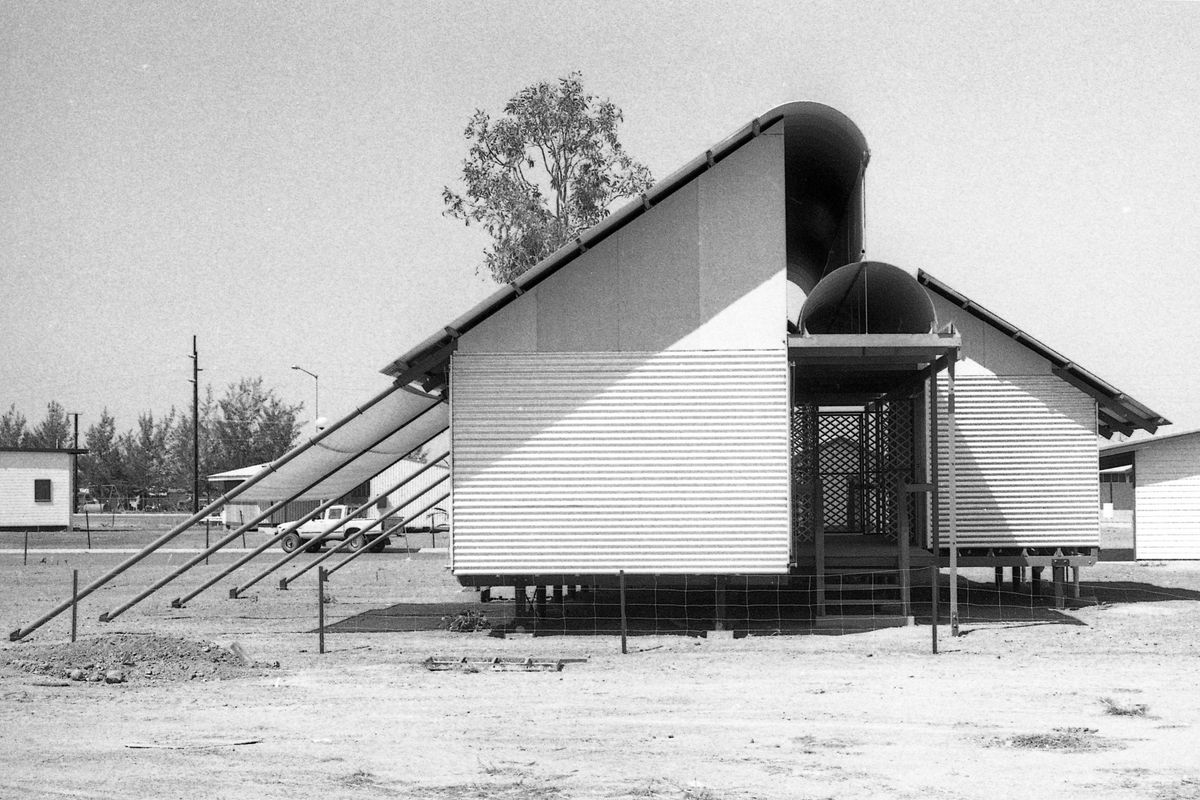

Green Can, Karama, Darwin, NT, 1982.

Image: Troppo

Darwin’s social informality suited the Troppo temperament. Harris and Welke worked, played and partied hard (as we all did); their wide-reaching friendships turned into client circles as people paired off, saved money and sought to put down roots.

Paul Everingham, then chief minister of the Northern Territory, made a startling admission that would help Troppo Architects’ fortunes immeasurably. The government had realized, he said, that it couldn’t keep building houses that people didn’t enjoy living in and couldn’t afford. He launched a low-cost housing competition for the Top End.

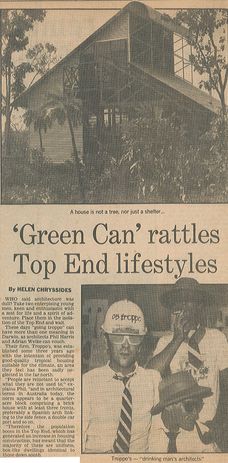

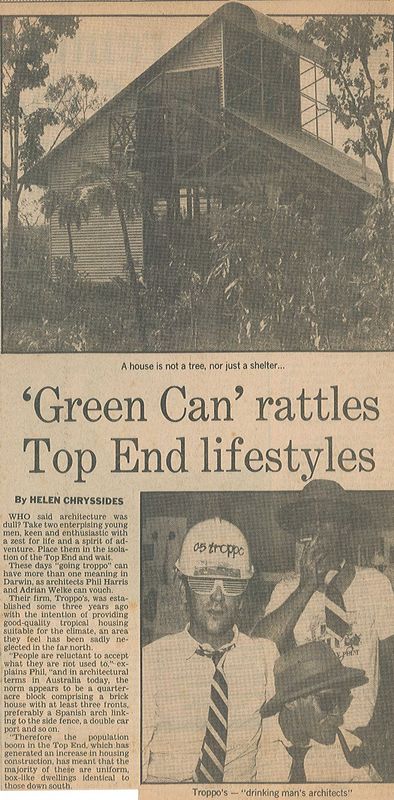

“‘Green Can rattles Top End lifestyles,” The Australian, 1983.

Troppo produced the Green Can – an elevated, curved, corrugated-iron-roofed house that drew both accolades and outrage, strong reactions that delighted its creators. It cost a mere $34,000 to build and won them the first of many awards.

“It was Japanese-style post-and-beam with optional walls, as open or closed in as you wish,” says Harris. “It was a clear statement of Troppo’s structural ideas, how loads were to be carried and braced against.”

Meanwhile, the duo was documenting the history of tropical housing in the north. Punkahs and Pith Helmets was their self-published attempt to record their design philosophy and its debt to earlier models.

If their mantra appeared simple – keep out the sun, work with the breeze, savour the change of seasons – it has withstood the test of time. Today, on Troppo’s website, there is a lyrical but essentially unchanged credo. “A non-constant architecture that responds to the morning, the evening, the season, the heat, the cold, the sun, the rain, the moment that will never pass again.”

“We described ourselves at the time as radical traditionalists,” recalls Harris, “since there was nothing new in what we were doing, but just in the way we were putting things back together.” They drew contemporary inspiration from architects like Russell Hall, who designed for Papua New Guinea’s tropics, as well as Gabriel Poole and Glenn Murcutt.

Meeting their idol Murcutt – with whom they would later collaborate on award-winning work – was typical Darwin happenstance. “We had made a mobile out of a newspaper article about him and hung it in our shop window,” says Harris. “One day, Glenn happened to be in Darwin, walked past the shopfront and came in. He said, ‘What am I doing in your window?’ So we went off and had a few beers.”

In 1981, Harris and Welke bought an old elevated house for $450 and moved it to a site in Coconut Grove to share. The arrival of their respective partners, Annie Hastwell and Fran Bonney, required separate dwellings and, as children arrived, the occupants extended decks, draped canvas sails and added annexes.

Everyone who visited a Troppo residence was struck by its casual but comfortable nature. It was the perfect eyrie for the laid-back Territorian with sarong around hips, beer can in hand.

Before long, Coconut Grove was dubbed “Troppoville” (“Or ‘Shantytown,’ depending on your point of view,” quips Welke), as friend-clients moved into a cluster of Troppo-designed houses. “In a sense it was an idyllic scenario,” muses Harris. “In life, you need food, sex and shelter. It was great to make that shelter with friends.”

I mentally note that “friends” could include hissing fruit bats roosting a metre from one’s bed, in lush foliage that formed a dappled screen around the house. Or a warm gecko clambering across a sleeper’s arm and falling, “plop,” over the flywire-less balustrade. “In the Troppo manifesto, it says quite clearly that the landscape is part of the house,” comments Harris, tongue-in-cheek.

There were steep learning curves – for both designer and client. At one house launch party, Welke was mortified when a massive storm broke overhead and rain poured in through a flyscreened gap tucked under the bullnose roofline. It drenched the guests and the house interior.

Kaiplinger House, Coconut Grove, Darwin, NT, 1983.

Image: Patrick Bingham-Hall

“Phil was in Italy at the time, and I contemplated going there as well – on a one-way ticket!” says a grinning Welke. “But the owner, Chris Kaiplinger, wasn’t fazed; he just got up and replaced the flywire with louvres. He knew the experimental nature of the building and fixed the problem. Those early buildings were simple and the importance was how the whole functioned.”

Harris interjects. “The point is we’re about not over-documenting but getting involved with the builder and the client as an evolution of ideas. That’s so, so important and it’s so what we’re told not to do in our profession.”

The popularity of Troppo buildings and the fresh ideas behind them led to bigger commissions and a wider sphere of influence. Most prominent among the firm’s clients was Defence Housing Australia, which was seeking a solution to housing problems on its Northern Territory bases, which were affecting military morale.

“They conducted focus groups long before it was fashionable, and asked soldiers’ spouses for their opinion, and we worked that way too,” says Harris. “Troppo was invited to submit eleven prototypes, which had an impact on the builders we worked with.” More projects ensued at Larrakeyah Barracks and HMAS Coonawarra naval base (1992).

Eleven years after the Green Can, Troppo had won the Robin Boyd Award for its Medium Density Precinct 2 at Larrakeyah (1993) and a special jury award from the Institute for its contribution to architecture in northern Australia (1992). In 1994, Troppo and Murcutt jointly won the Sir Zelman Cowen Award for Public Buildings for the Bowali Visitors Information Centre in Kakadu National Park.

Bowali Visitors Information Centre in association with Glenn Murcutt, Kakadu National Park, NT, 1992–94.

Image: John Gollings

“The Australian Nature Conservation Agency [now the Department of the Environment] was blessed with really great people working closely with Kakadu’s traditional owners,” recalls Harris. “From day one, we were part of the interpretive team working out what the building was for in concert with the people who would use it.”

Bowali’s big overhanging roof owed its inspiration to Kakadu’s natural gallery sites at Ubirr, where generations of people lived, painted on rock walls and surveyed the vast wetland plains.

Dappled shade and spirit-reviving breezes play along the entire length of this giant outback shed. These atmospheric qualities are as tangible to the visitor’s senses as material features such as the elegant hanging slats, elevated platform floor and curved iron roof.

“The changing shadow play of those slats we call ‘architecture by accident,’” says Harris. “That slat-screened verandah defines the building; it’s where six busloads of visitors arrive at once and they need shade and a cool place. It’s a building without a front door and the front counter is a large rock on the verandah. You’re ‘in,’ yet you’re still connected with the great outdoors.”

Bowali is among dozens of commissions that have brought Troppo in pleasurably close contact with Aboriginal culture. “Their linkage between culture and landscape is immense and it dwarfs our efforts,” says Harris. “For forty thousand years, they made minimal impact on their environment and architecture was never part of their lifestyle. [Yet] they knew how to seek shelter and shade, how to store things, conduct ceremonies and look after their dead. There’s an incredible magic to that outlook – who needs to hang paintings on the wall when you can wake up to the birds and see what sort of day it is? There’s a luxury that comes from living that way.”

“We’re still trying to learn how to be Australian, and rule number one is to connect with your environment,” adds Welke. “We often have to take bureaucrats or officials out bush into communities where there are no accommodation facilities. Almost without exception, those people feel incredibly uncomfortable camping out in their own country. They’re terrified of where they are; they fear for their lives.”

By the mid-1990s, Troppo Architects had garnered many awards and grown into a twenty-person practice.

“We became nervous about the number of mouths we had to feed and the offer of defence housing work in Townsville seemed like a good opportunity,” says Welke. Troppo opened a Queensland office, eventually headed and shaped by colleague Geoff Clark.

Welke and Harris had progressively remodelled and enlarged their houses over the years. Families, careers and architecture itself was always “an evolving thing.”

Then came the demands of higher schooling, work opportunities for their spouses and the needs of ageing parents. Harris and family moved back to Adelaide in 1999, where he set up a Troppo office, now co-directed by Cary Duffield.

The Welke tribe headed back to Perth, where Adrian has run a Troppo office since 2003. Much of his work has been in regional western and central Australia, from health clinics and aged-care facilities in remote places like Pukatja to resort chalets in Kununurra and Esperance.

The original Troppo office was left in the capable hands of Greg McNamara and Lena Yali. “It was a wrench to leave, because Darwin was Troppo heartland,” says Welke. “But it was a stroke of luck that Greg and Lena put up their hands to take over the Darwin office.” (In a tragic footnote, the couple was killed in a car accident in 2011. Harris, who was a passenger in the same car but was unhurt, now leads the practice with Jo Best.)

Troppo’s footprint has expanded across the nation, but not as the result of any grandiose plan. It just suited them to live differently, yet still work closely. “Adrian’s been trying to go back to farming from the start,” quips Harris. “And Phil kept taking breaks in Italy, which kept him sane,” is Welke’s quick rejoinder.

“It has proven that refreshing the practice at the top with new minds only takes Troppo further,” says Harris. “The way Adrian and I have always worked is not to be in each other’s faces at the drawing board. A job might change as it moves between the project team members, but we have ultimate faith in the outcome.”

Does Troppo Architects – more disparate and dispersed these days – still adhere to a fistful of basic principles? The answer is an emphatic yes, says the pair, citing structure and environmental connectedness as two enduring ones.

Bush Verandah House, Girraween, NT, 2010.

Image: Peter Eve

“Adrian has always had a great mind and eye to what is a good structure and what nuts and bolts are needed to come together,” says Harris. “We don’t design something and then get some engineer in to find out how it could work and solve the problems. In our minds we’ve already built this thing, stick by stick, and I’m proud of that.”

And connectedness? “Designing is not static, it’s always about the journey through the building or site, collections of buildings and half buildings like breezeways and courtyards. It becomes an ecological way of thinking, so the building becomes part of a street or site. Everything should interconnect.”

Our conversation has led to some of their latest projects, which include a green housing project in Adelaide and a winning entry in a Northern Territory government competition for a new sustainable city in the savannah.

In a sense, the Weddell Sustainable City urban design brief is Troppo’s original housing challenge writ large. Back then, Everingham was exasperated by poor houses in the Top End; the challenge now is entire cities and their unsuitability in tropical climates and biodiverse environments.

Says Harris: “When it comes to suburban expansion of the usual pattern, we need to say ‘Fuck it, that’s not working any more, let’s get rid of it.’” Troppo’s Weddell city scheme is based on a walkable village model, integrating public transport, rainwater harvesting, waste regeneration, solar power and environmental stewardship. All these are commonly used buzzwords, but Troppo would argue they have been part of its lexicon from the start.

“We never saw sustainability as separate, but as the only way to do things,” says Welke. “We were not about saving the world, but acting commonsensically – making do with less for good reasons.”

So what about the idea of permanence, I ask, as lunch draws to a close. Troppo is indisputably part of the social, economic and architectural history of the Top End. If Welke and Harris fought hard for earlier built heritage, and documented much of it, do they hope for similar consideration?

“We’re not precious about things we’ve done,” says Welke with a shrug. “Our legacy is a scrapbook of buildings that reflect our philosophy. It’s the whole 3000 or so job numbers of what we’ve produced. Everyone’s disappointed if something’s knocked over or adapted horribly, but you’re overjoyed if it’s adapted positively.”

Harris chimes in: “The work has been regarded well and we’re serving individuals in the community, and that’s a privilege.

“And there are some fantastic young practitioners out there. We’ve learned from them and I’d like to think they’ve learned from us. And I do think there’s an emerging Australian architecture that’s far better [as a result of] the last thirty years of smaller players.”

Phil Harris and Adrian Welke will be speaking nationally in Brisbane, Townsville, Sydney, Adelaide, Canberra and Melbourne as part of their Gold Medal tour.

Source

People

Published online: 7 Oct 2014

Words:

Victoria Laurie

Images:

David Sievers,

Jo Best,

John Gollings,

Patrick Bingham-Hall,

Peter Eve,

Timothy Burgess,

Troppo

Issue

Architecture Australia, March 2014