The cliché is that necessity is the mother of invention. But crisis pushes everything up another notch. Throughout history, pandemics, economic recessions and wars of global proportion have been catalysts for quantum leaps in medicine, technology and material science. Human disasters wreak havoc and we react as if in battle. Words change as we “fight” the crisis and “turn back the tide.” But from desperate responses to a devastating, often destructive cataclysm comes also a level of sinister benefit – and architecture is inevitably a recipient. The architecture of crisis almost always has a form of wicked novelty because the parameters of crisis are almost always new and unknown, requiring novel solutions to conditions never before experienced. Generally, the architecture of crisis arises in three ways: first, as a direct and immediate response to the crisis; second, as a project to relieve crisis; and third, as a form of future-proofing in case the crisis hits again. But there is also a fourth, often forgotten, aspect to crisis: its memorialization. So, historically, what has this architecture of crisis looked like? Have cities and urban spaces been reshaped by crisis and what evidence remains?

Response

Pandemics throughout history have resulted in mass deaths of unprecedented scale. A key spatial problem was how to deal with overwhelming numbers of dead bodies. In London, during the Black Death (1346–53) and the Great Plague (1665–66), “plague pits” were common. Huge holes were dug in city churchyards but these soon overflowed and larger, dedicated pits housing scores of corpses were excavated at the city’s fringes. It is thought that around 50,000 bodies were buried in London’s largest plague pit, at Charterhouse Square in Farringdon. The major problem of this expedient disposal strategy was that, for centuries afterward, the land was considered contaminated – though today, most have been built over and only now, when excavating for new building, are the true numbers of these pits coming to light.

By the time of the Spanish influenza (1918–20), the problem of mass graves had not gone away. Philadelphia, one of the worst-hit US cities, experienced nearly 1,000 deaths a day at the peak of the pandemic and mass graves had to be dug using steam shovels, while six cold-storage plants were used as supplementary morgues. This temporary repurposing of existing buildings, structures and urban spaces is a hallmark of crisis.

In 1882, during a major smallpox outbreak in Great Britain, former Royal Navy ships were requisitioned, de-masted, linked together, reconfigured as smallpox hulks, and moored at desolate Long Reach, 27 kilometres downstream from London Bridge. One of these floating hospitals, the Castalia, was a failed twin-hulled paddle-steamer with five ward blocks erected on its deck. During the Spanish flu, the Drill Hall of the Naval Training Station in San Francisco became a giant sleeping area divided by person-high fabric sneeze screens to protect against the spread of infection. Likewise, in Australia, the Royal Hall of Industries at Sydney’s Royal Agricultural Society Showgrounds was turned into a morgue and, in Melbourne, the Great Hall of the Royal Exhibition Building became a vast temporary hospital. Also converted to hospitals were dozens of schools like Nowra State School in country New South Wales and Armadale State School in suburban Melbourne.

Hospital beds in Melbourne Exhibition Centre’s Great Hall during the Spanish influenza pandemic, c. 1919.

Image: Museums Victoria

Major public outdoor spaces were also requisitioned. The Jubilee Oval in Adelaide and the Tenterfield Showgrounds in Ipswich, Queensland, for example, were used as influenza quarantine camps, becoming vast tent cities overnight. Rapidly erected and well aired, tents had also long been an intrinsic form of wartime shelter and it was war in the twentieth century that saw the tent’s portability inspire larger and more permanent forms, with the proliferation of inventive designs for prefabricated structures for barracks, hospitals and hangars.

World War I bequeathed the semi-cylindrical, corrugated iron-clad form of the prefabricated Nissen hut (1916), adapted by the Americans during World War II as the Quonset hut (1941). In Architecture in uniform , Jean-Louis Cohen notes that wartime advances in plastics, the chemistry of resins and adhesives, laminated timbers and plywood technology (like Charles and Ray Eames’s leg splint that influenced their plywood chair designs) signalled the fact that “Innovation became an official policy in all the nations at war.”1 In addition to canvas Butler hangars and timber “igloo” structures, war also bequeathed the portable, prefabricated Bailey bridge (1940–41) and Marston Mat, the pierced steel planking that enabled airstrips to be constructed virtually anywhere, including remote jungle sites in Papua New Guinea and the Philippines. Many of these innovative materials and structures continue to be used today.

Some inventions, though, had short lives. During the Spanish flu, Kodak Australasia created the “inhalatorium” for the employees at its Abbotsford factory in Melbourne. Twice a day and for four minutes at a time, 10 workers stood on each side of a linear, house-like volume and pressed their heads against oval-shaped openings from which steam carrying a zinc sulphate solution was sprayed onto their faces. This was meant to “disinfect” their throats and air passages. Needless to say, it didn’t work.

Recovery project

While the immediate response to crisis draws into play the refashioning of landscape for mass death, the repurposing of existing structures, and the use and invention of ephemeral and prefabricated structures, relief from crisis also relies heavily on the economic and psychological healing powers of the “recovery” project. Australia’s two most notable recovery projects became national icons. The construction of the Great Ocean Road (1919–32) in Victoria was initially intended to give work to 3,000 returned servicemen and serve as a memorial to those killed in World War I. By the time of the Great Depression (1929–32), it was 234 kilometres long and not only the largest war memorial in the world but also a source of work for hundreds of unemployed Victorian men. It was the same with the Sydney Harbour Bridge (1923–32). Nicknamed “The Iron Lung,” its completion, sponsored by Jack Lang’s Labor government, provided much-needed employment during the Great Depression. At a time when more than one in five adult males was without a job, “the people’s bridge” effectively became the lifeblood of the New South Wales economy. Other examples of public sector stimulus include the employment in 1933 of nearly 500 men to complete the landscaping of Melbourne’s Shrine of Remembrance. The private sector also provided the occasional recovery project. In 1932, as a way of providing employment and boosting faith in an improving economy, Melbourne’s Manchester Unity Building was built “around the clock” in less than a year in eight-hour shifts. This was the first time that a construction schedule was used to track and manage a building’s completion in Australia.

Sydney Harbour Bridge under construction, 1930.

Image: National Museum of Australia

However, these Australian efforts were small beans compared to the most celebrated recovery project of the Great Depression: the capital works projects of US Democratic President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal (1933–39). Established by executive order in 1935, the Works Progress Administration employed more than eight million Americans in projects that ranged from bridges and airports to hospitals, parks and schools, and the planting of 24 million trees. The Tennessee Valley Authority (1933–), the Lincoln Tunnel in New York (1934–36), the Hoover Dam (1931–36) in Colorado, which employed 21,000 men, and the Federal Art Project, which gave work to artists like Diego Rivera, Mark Rothko, Willem De Kooning and Lee Krasner, were all New Deal initiatives. The US Civilian Conservation Corps, created by Roosevelt in 1933, put more than three million men to work on national parks infrastructure like “comfort stations” and lookout towers. While the economic stimulus was profound and America’s built environment was transformed, even this extraordinary effort at recovery was not quite enough.2 It was only with World War II that the US achieved full “recovery,” war being its most effective motor.

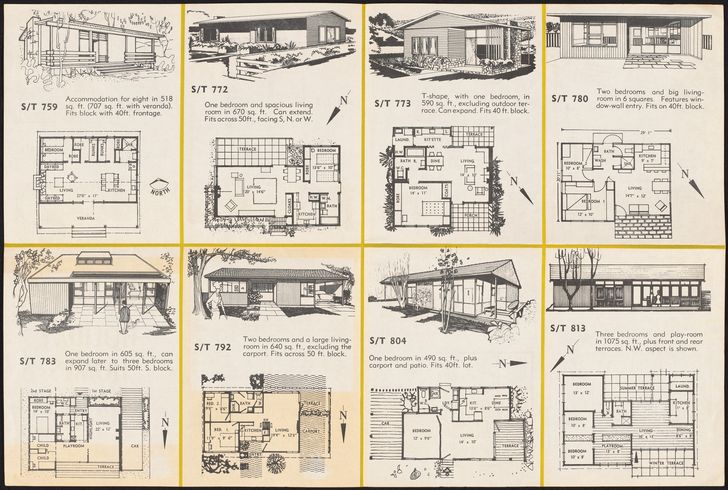

Here in Australia, the Royal Victorian Institute of Architects Small Homes Service, founded in 1947, and its offshoots in other states, were, in many respects, a direct outcome of the dire housing shortage brought on by World War II. This was a local chapter’s response to crisis. War enforced a revision of expectations about housing affordability and the design of interior space, ushering in, by force of circumstance, innovations such as the open plan, the increased use of glass and the lowering of roof pitches. Good design was to be a panacea to the so-called jerry-builders’ response to the housing crisis. A similar sense of urgency led to Victorian Public Works Department chief architect Percy Everett’s development of the LTC (light timber construction) school system (1953) to not just relieve the post-war demand for new schools but also to radically improve the lighting and ventilation of classrooms.

Folded booklet of house plans prepared by the Small Homes Service New South Wales, conducted by the Royal Australian Institute of Architects (New South Wales chapter) in conjunction with Australian Home Beautiful at David Jones, Sydney.

Image: Courtesy National Library of Australia

Future-proofing

The cyclical nature of crisis has meant that societies have attempted to future-proof their cities against repetition of disastrous conditions, or at least to build in some form of resilience to a crisis’s reappearance. Often, this takes the form of major infrastructure. The 1859–65 re-sewering of London was a direct response to The Great Stink of July and August 1858, when untreated human waste and industrial effluent on the banks of the River Thames were blamed for the city’s foul miasma, which was thought to spread contagious diseases such as cholera. Almost every pandemic encouraged a renewed focus on fresh air and ventilation as curative devices – and architecture could play a vital role here. Indeed, many of the key tenets of modernist urbanism were born of the ongoing nature of the miasma “problem,” encouraging urbanists to future-proof against urban squalor as a future-proofing against pandemic. Le Corbusier even argued for the generous spacing of buildings as a strategy for reducing bomb damage in the case of attack from the air.3 In Australia, future-proofing against urban slums that had grown during the Great Depression saw the formation, in 1936, of New South Wales’s Housing Improvement Board and the South Australian Housing Trust, and, in 1938, the Housing Commission of Victoria.4 Similar bodies in most states were in place by the end of World War II. Here was a case of government stepping in to future-proof its citizens with the design and construction of affordable housing using in-house design offices and panels of consultant experts. Nationally, housing commissions became the major promoters and providers of affordable housing from about 1945 until the early 1980s.

Memorial

Crisis also raises the question of memory. War, throughout history, has always spawned permanent reminders of lives lost. But, memorials to pandemics and economic recession are remarkably few. They also take a different form. The private headstones of the 12,000-15,000 people who died from the Spanish flu in Australia are largely hidden from public view. A rare exception is the granite obelisk at the Woodman Point Recreation Camp at Munster, Western Australia – a memorial to Sister Rosa O’Kane, who died after nursing victims of the epidemic on board the SS Boonah, which had returned to Fremantle from the battlefields. It was only in 2002 that an “Influenza pandemic window – Heroes and heroines of 1918–19,” by German artist Johannes Schreiter, was finally installed in the Medical Library of the Royal London Hospital in the church of St Augustine with St Philip in Whitechapel, and only in 2018 that a modest stone memorial seat was erected in Hope Cemetery, Barre, Vermont, USA with an inscription stating that the Spanish flu “killed more Americans than all the combat war deaths in the 20th century.” This all goes to the point that death through pandemic or recession has never been considered glorious or an act of national sacrifice, as has death in war. Instead, pandemic and recession suffer from an almost deliberate cultural amnesia in terms of physical commemoration.5 Memorials to human frailty are few and far between.

What these examples show, however briefly, is that the architecture of crisis is an intrinsic and everyday part of urban existence that continues to shape our cities, whether we like it or not. Remarkably, ventilation continues to remain key, as does the right to private outdoor space. While the concept and prospect of vaccines make many of these historic examples seem quaint, old-fashioned and temporary, the architectural lessons of crisis remain with us. There will always be a need for certain spaces to be repurposed during crisis (I write this piece from the sixteenth floor of a downtown Melbourne hotel, where I’m quarantined in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic after returning from the United States). There will always be a need for ephemeral structures to cope with the spatial challenges of immediate crisis. There will always be a need for emergency domestic shelter. There will always be a need to reshape and reform our cities in preparation for the next crisis. And, importantly, there will always be a need to remember such events through some form of memorial, whether useful or symbolic. Yet what is striking about all of these historic examples is that they have relied on the vision and leadership not of individuals, but of governments, institutions and agencies prepared to work collectively to take on the moral and economic responsibilities of crisis and its three challenges: relief, recovery and reform.

1. Jean-Louis Cohen, Architecture in uniform: Designing and building for the Second World War (New Haven: Canadian Centre for Architecture and Yale University Press, 2011), 57.

2. Kiran Klaus Patel, The New Deal: A global history (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2016), 45–90.

3. M. Christine Boyer, “Urban operations and network centric warfare,” in Michael Sorkin (ed.), I ndefensible space: The architecture of the national insecurity state (New York: Routledge, 2007), 57.

4. Renate Howe, “Housing Commissions,” in Philip Goad and Julie Willis (eds.), The Encyclopedia of Australian Architecture (Melbourne: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 343.

5. Nancy K. Bristow, American pandemic: The lost worlds of the 1918 influenza epidemic (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012), 6–11.

Source

Discussion

Published online: 3 Sep 2020

Words:

Philip Goad

Images:

Courtesy National Library of Australia,

Museums Victoria,

National Museum of Australia,

Ted Hood. Courtesy State Library of New South Wales – Home and Away – 2270.

Issue

Architecture Australia, September 2020