The Biggest Estate on Earth by Bill Gammage.

Simultaneously about landscape, country and identity, The Biggest Estate on Earth is a large work that melds (Indigenous and non-Indigenous) history and art history with anthropology, botany and environmental science. The Biggest Estate on Earth is a highly reviewed book, and many of the reviews diverge in their opinions. The breadth of the content is diverse, but the development of the arguments presented is, in some specialists’ views, limited, and as such it has attracted a range of criticism.

James Boyce, writing for The Monthly, states, “The Biggest Estate on Earth is meant to prove how persuasive the visual and documentary record on the impact of Aboriginal land management ultimately is.”1 Timothy Neale of the University of Melbourne is critical of how the documentary record is presented, analysed and argued. He is critical of many aspects of the book, from its wandering written style to the scientific assumptions about environmental land management, and to the source of Gammage’s anthropological theory.2

It appears that The Biggest Estate on Earth is a book that divides, and for that reason alone it should be read, digested and reflected upon. Despite its critics, the book has won a slew of Australian literary awards, including the Prize for Australian History in the 2012 Prime Minister’s Literary Awards.

When I was asked to review this book, I asked myself, “What can I bring to another reading of this work?” I am an architect. I am not a historian, an art historian or a botanist. However, I have a close connection with the land and have worked with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people on design projects for nearly twenty years. I am a designer and a farmer from north Queensland with a keen emerging interest in Indigenous tropical ethnobotany. When the opportunity arose to review Bill Gammage’s book I was very excited.

The Biggest Estate on Earth is an interesting read, albeit long and somewhat repetitive. It is easy to digest and contains nearly one hundred pages of colour plates of the Australian landscape as depicted either in paintings by early landscape artists such as Eugene von Guerard and Joseph Lycett, or through photographs. The plates are supported by historical extracts – descriptions of the landscape by non-Indigenous explorers and early settlers. In the first one hundred pages Gammage presents some 1500 historical examples and descriptions of the Australian landscape from between 1788 and 1850, from across Australia. His argument is clear and repeated consistently throughout: Australia was a designed and made landscape, which many new Europeans likened to a park.

Trees planted as if for ornament, alternating wood and grass, a gentleman’s park, an inhabited and improved country, a civilised land. Much of Australia was like this in 1788 [page 14].

For those with little time, chapter nine, The Capital Tour, explores the landscape histories of our capital cities, and the descriptions of Sydney and Brisbane are fascinating.

Much of Gammage’s book refers to land management through the controlled use of fire, otherwise known as “fire-stick farming.”3 Gammage describes and provides analysis of large-spread environmental land management through fire prior to non-Indigenous occupation of the land.

Eucalypt seedlings can’t grow in rainforest: there is no light. How did those giant eucalypts get there? Clearly, when they were young there was no rainforest. Without fire rainforest has returned, so fire once kept it back. No stray marauder can do that. It needs determined burning when conditions are right … Eucalypts topping rainforest indicated land people once went to great trouble, working against the country, to clear and keep clear [page 13].

Fire to regulate fuel, make mosaics, control animals and insects, and clean country gave the land a certain look … Correct burning was deeply satisfying, announcing managers who respected the land and the dreaming [page 184].

In Arnhem Land in the late 1990s I observed Yolngu people use and move fire like any other tool. Camp fires were picked up, transported and relocated to new areas to suit the weather and activity required. Controlled grass fires were lit in the time of heavy dew as we walked towards a hunting ground, to clean up the country and provide new green growth for game. When considering yard design in Indigenous housing, I decided I was against the creation of singular hearth places because fires are not stationary and there is no single preferred hearth to cluster around as we do in contemporary architecture. In Arnhem Land (and many other places across Australia) fire is a dynamic tool adapted and used to suit the purpose required. It is respected but not feared.

In the Weekend Australian on 12 January 2013, after the devastation of the Dunalley Bushfires and those in Victoria and New South Wales, there was much discussion about Australian bushfires and the inherent fear of fire in modern urban populations. Even in rural areas, any discussion on “controlled burning” for land management is met with trepidation and suspicion. Gammage argues that what we have created in national parks and state forests through the lack of controlled burning is a wild Australian landscape that is out of our control. What existed at a national scale in 1788 was a designed and managed landscape optimized to support an abundant and organized hunter-gatherer lifestyle or mobile farming.

The Biggest Estate on Earth has made me re-examine my own regional landscape in north Queensland. I learnt how to read and respect country in a rudimentary way while I was in Arnhem Land. I have also learnt that in regional towns and cities Indigenous ancestors can still be read, seen and felt in the geography and the landscape, if you are open and privy to the ancestral stories, places and lore. Gammage’s book has unveiled my eyes to yet another reading of the landscape, one that searches like a detective for historical changes in vegetation types, size and stands, and remnants of designed and made riparian native fruit corridors, rainforest fishing holes and hill slopes once grassed, now open eucalypt forest.

Some of Gammage’s discipline-specific theories may well be questionable, but the intent of this book is not to argue over scientific perspectives. It is to provide a reading of Australian history and landscape that will change how you consider Australia. I heartily recommend it.

Bill Gammage, Allen & Unwin, 2011, 384pp, RRP $49.99.

1. James Boyce, “The Biggest Estate on Earth: How Aborigines Made Australia by Bill Gammage,” The Monthly, December 2011, themonthly.com.au/biggest-estate-earth-how-aborigines-made-australia-bill-gammage-james-boyce-4308 (accessed 12 April 2013).

2. Timothy Neale, “Review of The Biggest Estate on Earth by Bill Gammage,” Academia.edu, academia.edu/1540825/Review_of_The_Biggest_Estate_on_Earth_by_Bill_Gammage (accessed 12 April 2013).

3. R. Jones, “Fire-stick Farming,” Australian Natural History, 16:224, 1969.

Source

Discussion

Published online: 13 Dec 2013

Words:

Shaneen Fantin

Issue

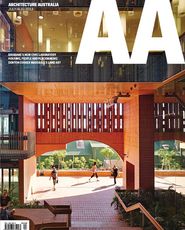

Architecture Australia, July 2013