Not quite a manifesto

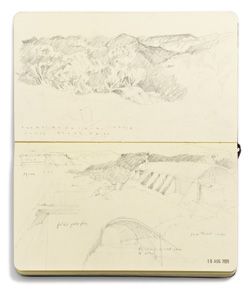

Sketchbooks from jurors Rachel Hurst, made while on tour.

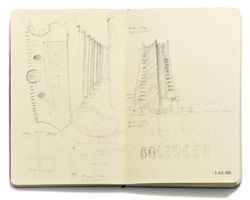

Sketchbooks from jurors Peter Malatt, made while on tour.

National awards programs are like orthodox histories: well intentioned but selective, always partial and rarely magisterial, biased because choices have to be made, a sprinkling of gems and genuine insights matched by workaday and worthy pronouncements, not quite a manifesto but never quite loaves and fishes for all, inevitably self-portraits in some way of their authors – in this case, a jury bearing the load of their professional peers. This year has been no exception. If one can read the 2009 National Awards as a litmus test for the current state of Australian architecture, some salient messages can be read in the jury’s decisions. Some I understand. Others I couldn’t fathom. But that’s what it should be. For if architectural discourse is to prosper in this country, there needs to be a critical mass of divergent opinion on what makes an architecture of excellence, and hence the ability of a range of architecture cultures to co-exist and for debate to rage over, yes, sometimes timeworn party divisions of whether architecture can speak or simply reside quietly in the city and, yes, whether our perception of what it means to dwell cannot shrug off the spectre of the beach house as the only laboratory for exploring the idea of Australia’s home, and hence resoundingly restate the locus of class in which Australian architects seem only able to operate or even think.

Take the winner of this year’s Sir Zelman Cowen Award for Public Architecture, Johnson Pilton Walker’s National Portrait Gallery in Canberra. It’s impeccably detailed, modestly and appropriately scaled, and embedded within an international pedigree of how one thinks about gallery space that defers gracefully to Kahn, to the salons of yore, and to an Indian summer of the modern that the now defunct National Capital Development Commission was hoping Canberra might become. But perhaps the gallery’s most important attribute is its acknowledgment and understanding of Canberra as a work in progress, as a mannered Washington and not a proudly parochial Barcelona. As such it represents a genial knitting of the capital’s hopes, a piece slipped into the family jigsaw of the Griffins’ Antipodean City Beautiful. Such a considered position therefore might account for the jury’s perhaps surprising identification of Architectus’s quiet brilliance at the Electron Microscopy Centre at Monash University, which possesses an almost negative architecture of atectonic neutrality, something of which the Smithsons might have been justifiably proud. It also might account for the jury’s almost universal shunning of digitally derived formal play and the architecturally garrulous, reserving acclamation for it only on the interior. In short, condoning it when largely hidden from public view, rather like Nikolaus Pevsner waxing lyrical over the soaring, spiritually transcendent Bavarian baroque interiors of Balthasar Neumann’s churches and ignoring its country classical coat outside. Thus ARM’s gorgeous timber interior for Melbourne’s Recital Centre, a tour de force of contoured plywood, is an acceptable frisson of excitement, titillating and rather naughty, but its bravely enigmatic exteriors are verboten. John Wardle’s clever interiors for the Jane Foss Russell Library at the University of Sydney fall into the same category: an internal landscape with a carpet pattern that makes one gasp but fulsome as a rich topography of habitation that takes advantage of the university commission as a place of potential architectural invention rather than reproducing a sad simulacrum of the corporate world.

By contrast, glamour raises its pretty head with Ivy in George Street, Sydney. This is literally a social condenser for hedonists, not earnest workers in Soviet grey. Architecturally more Goldberg than Golosov, more Moretti than Melnikov, it’s a stylish period piece of urban theatre, a pleasure palace whose fortune will rely on constant use, though its architectural bones, like an expensive suit, should weather any period of slumming it. As an invented new type, it will be intriguing to follow its future. Another celebrated but altogether different type is the school. Candalepas Associates’ tough talking for a Greek Orthodox community’s multi-level urban school is a foretaste, surely, of deserved larger work and a reminder of the vigour of the technical and further education work that emerged from the NSW Government Architect’s office in the 1960s, much of which is now unloved and at risk. Highlighting model typologies has clearly been of interest to the jury, especially so in terms of housing. All four winners in the individual house category were beach houses but their jury citations stressed their suitability as models for a denser city – perhaps this was to excuse the profession from participating in the bedevilled economic, social and aesthetic field of the everyday suburban home? Or is the beach house being proposed as a vehicle for genuine experiment? It’s not quite clear. But this preoccupation continues with the jury’s awards to Balencea, Wood Marsh’s fluted, reflective shaft of high-rise apartments, and Candalepas Associates’ medium-density Pindari apartments and townhouses. In this sense, then, all of the winners in the domestic category deserve intensive scrutiny and critique, not at the level of form but in their plans, sections and adopted construction practices. This represents a task of research that, one can only hope, might lead to a stamping out of the rampant practice of windowless bedrooms, “borrowed” light, lack of cross-ventilation, and impossibly cruel beliefs in existenzminimum.

The message from the sustainability category was the heartening adoption of responsible design strategies in regional centres like BVN and Gray Puksand’s all-colourful Bendigo Bank. There is a feeling amongst these works that, like the fervour for designing for disability in the 1980s, thinking about sustainability has become part of common practice, rapidly giving birth to a new Esperanto of corporate architecture. A strong message from the jury concerns heritage. The named award to Falkinger Andronas for their restoration of William Butterfield et al’s St Paul’s Cathedral in Melbourne is an accolade for nearly a decade of extraordinary work that has gone largely unsung. The same firm was responsible for the restoration of William Wardell’s bluestone masterpiece St Patrick’s Cathedral, Melbourne. This is specialist work and represents the maintenance of excellence and the fostering of a concept of patrimony. It’s a special form of stewardship. Other heritage awards, to Luigi Rosselli for his refurbishment of a Leslie Wilkinson house and to Gregory Burgess Architects and Lovell Chen for their part in restoring and adding to the Sidney Myer Music Bowl (1956–59, winner of the 25 Year Award), signal that top design architects and heritage professionals can collaborate and produce exemplary work. It was, and still is, a path trodden by the likes of Scarpa and Zumthor, and the ingenious adaptive reuse of existing buildings is a vast field of untapped potential.

Earnest pleas aside, it was gratifying to see some edginess amidst the genuflections. Sprinkled through the selection are Bellemo & Cat’s Polygreen, a child’s unfettered scribble as a house; Choi Ropiha et al’s extraordinary red neon public stairs as public building in Times Square, New York (Go Straya!); and James Stockwell’s steel house at Kalkite, NSW, a mainland echo of Esmond Dorney’s insectile Tasmanian houses of the 1950s. These are little projects, certainly, but with big ideas and with a breadth of philosophical position, and spread across an astonishing diversity of geographic location. Good Australian architecture, it seems, is everywhere. As always, a heady tension remains in this sharing of the spoils of the best, between, as Tafuri would have it, “the path of ‘noncommitment’” and its “cloak of modesty” and the alluring promise of uncontaminated innovation. Would you have it any other way?

Philip Goad is Professor of Architecture and Director of the Melbourne School of Design at the University of Melbourne.

Offshore drilling

I’ve been working outside Australia for more than three years, and after some initial diligent maintenance of contact via attendance at conferences, vigilant reading of Institute newsletters and so on, my connection to the profession in Australia is now largely held by the tenuous thread of my Architecture Australia subscription. Magazines of the various international institutes of architecture give a sense of the obsessions of a profession, and the best annual sample of the Australian scene is presented in AA’s National Awards Issue.

Reviewing the award winners at a distance, via thumbnails and pdfs, is a challenge. I understand the judges visited all the Australian entries. The difficulty of assessing buildings remotely by still and video images is recognized in the international category appraisals by a note that the commentary was “information provided” rather than jury-generated. The International Committee of the Institute, representing the 700 or so members resident outside Australia, hopes, in future, to contribute to the organization and assessment of the international category, to overcome this limitation.

My other declaration of interest is that I’m reviewing as a practitioner, not a theorist or critic, so my reading of the buildings is always selfish; what can I learn from this project, how can my own design improve in response? Surveying the year’s winners in this context makes me somewhat envious of the cultural environment nurturing the works, the urbane settings, the apparent luxury of time (although I’m sure it didn’t feel so to the designers), of technological sophistication, of client erudition.

Several of the winning practices point to a new portability of architecture (or at least architectural services) in Australia. Woods Bagot (for the Qatar Science and Technology Park and Ivy, Sydney) and Hassell (their own office in Brisbane) are conspicuous exporters (and notably, both nurtured in Adelaide). Smaller firms are also producing new work interstate, incursions made possible largely by design competitions. Wardle (the University of Sydney Jane Foss Russell Building Library interior) secured the job via a three-project competition (also generating FJMT’s Law School), while Durbach Block completed the Sussan/Sportsgirl HQ after a competition under the sponsorship of Naomi Milgrom.

Neeson Murcutt has been recognized for two projects, in their home state of NSW (the Whale Beach House) and in Victoria (Zac’s House). Both are simple, modern vernacular beach houses, the Whale Beach home hugging the coastline and the Sorrento pavilion embraced by trees, both stereotypes well familiar to those who subscribe to Sydney/Melbourne rivalries. But beyond topographical typecasting, in the new crossing of state architectural lines three main classes of design generator might be recognized.

The first is the figurative – a sculptural, representational, literary yet evocative group of buildings that guide their inhabitants and observers to a place or way of being, that reveal the hand of a master. ARM’s interior for the Melbourne Recital Hall and MTC Theatre, although facilitated by scientific insights and computer technology, is “sensual” and “luxurious” and exists to “align the environment with the enveloping sensation of music”. It seeks a virtuosity to mirror that of the performances within. Wood Marsh’s Balencea apartment tower is similarly luxuriant, a glossy, slick, award statuette for those who have excelled, and a timely reminder that sustainable buildings need not be eaved and louvred (just Yve-ed). At the opposite end of the residential scale, and ambition, is a self-expressive home/studio by the architect/sculptor duo Bellemo & Cat. “Woven from a thread drawn from our first cocoon”, an earlier experimental abode, the house is symbolic in a domestic, private way, legible only to its intimates.

The second apparent classification is the procedural. This technique abjures architectural accountability for the object, controlling only the inputs into the production algorithm. In practice this creates an evolutionary, adaptive architecture, buildings with movable screens, apparently random patterning, control by the occupant or the climate. The Bendigo Bank HQ by BVN Architecture and Gray Puksand exemplifies this approach. The cladding adapts to the scale of the neighbouring heritage buildings by fracturing into different colours and surfaces. On the inside, atria puncture the large floor plates, bringing the changing light and character of the day to the desk. Of similar scale, FJMT’s Law Faculty at the University of Sydney knits itself into a campus context by capturing and amplifying pedestrian circulation patterns, upward through a cubic atrium and horizontally in a beam of lounge space over the public park. Again, variability is encouraged in the facade, this time generated by occupant-impelled kinesis of glass-sheathed timber screens.

My third classification, in some ways a subclass of the second, is the crafty. In this method the architect cedes some responsibility for the result to individuals, the contractor or tradesperson, a master-builder rather than master-architect approach. Although apparently guileless, frank and authentic, these buildings in fact shrewdly harness the skills, energy, dedication and history of an entire team, from designer to drape-hanger, to elevate the project from building to Architecture. Johnson Pilton Walker’s National Portrait Gallery celebrates the achievements of its concreters as much as those of the worthies portrayed in its cool, calm halls. Hassell’s own offices in Fortitude Valley remind clients of their own earliest experiences of architecture, the brick piers, timber studs and trusses alluding to the suburban domestic (although perhaps not of Queensland). Technologically and geographically far removed, though still relying on assured technique for its magic, Choi Ropiha’s TKTS booth in Times Square is evocative at both the urban and personal scales.

Beyond alluring form and expression, the most appealing project of the year is Ivy, a collaboration between inspired designers and a visionary patron (Woods Bagot, with Hecker Phelan & Guthrie and the Merivale Group). An urban leisure centre for adults-only fun, its generous program and civic-mindedness contradict my recollection of Australia as a culture retreating to the suburbs and the community church. Ivy proves that the vibrant, dense, mixed-up, stacked-up, twenty-four-hour-city we know in Asia is transferable (sans the neon). Now, if Justin Hemmes could just sort out Australian public transport …

Fiona Nixon is design director of RMJM, Singapore.