What were the aims and intentions of the editors of Architecture Australia and its predecessors?

How did they position the magazine? How did they represent Australian architecture?

Here, three former editors – Stella Tottenham, Ian McDougall and Davina Jackson – reflect on their time with the journal.

In addition, we have excerpted editorial statements from other moments in the magazines’ history.

Overt comment about where the magazine is heading usually occurs when the publication is changing somehow – editor, publisher, name, and so on. Things shifted often in the early part of last century. In the 1970s editors, publishers and RAIA policy also changed frequently.

As one looks over these comments various themes emerge, expressed in the language of the day – the concern to widen the audience, and the struggle to make the magazine financially viable are two which recur constantly.

In periods of stability such positioning statements rarely appear. Editors also sign the magazines in different ways. Colin Brewer, editor of Architecture in Australia from 1962 to 1972, was responsible for one of its more interesting phases. He made little editorial comment, but his vision for the magazine is apparent in particular in the striking covers he devised. Tom Heath, also edited the magazine for a decade, from 1980 to 1990. His highly considered editorials cover all manner of architectural topics, but there is little on the nature of publishing architecture, or his intentions for the magazine. We must read between the lines.

Editors play a key role in determining the direction of a publication, but a magazine is always an outcome of more than one person. Publisher, readers, advertisers, the Institute, all affect the magazine, as does the wider culture in which it is embedded. In some periods no editor is named, but there is a strong editorial board.

At others, editorials are signed by the president of the Institute.

Associate editors have also played key roles: Robin Boyd in the 1950s, Norman Day in 1977.

What follows is a brief snapshot.

We would also love to hear from other former editors who we did not manage to locate this time.

THANKS TO PAUL HOGBEN FOR HELPING COMPILE THE LIST OF EDITORS

ART AND ARCHITECTURE. FOREWORD

1904

“The Journal of the Institute of Architects of New South Wales” has met with a success far beyond the anticipations of its promoters, and it is now felt that its scope can be greatly extended. It has therefore been determined to enlarge the journal, and, by an alteration of the title to make it more comprehensive in its aim … it is believed that the new magazine will circulate far more extensively than its predecessor could be expected to do.

We recognise that there are many besides architects who love art and artistic things, and it is the support of these that we wish to obtain.

The new magazine will be known as “Art and Architecture,” and will deal with all matters pertaining to art, architecture, and artistic craftsmanship …The illustrations and general “Get up” will be superior to anything hitherto produced in Australia, and the articles will be contributed by the best writers on architecture and art-matters to be found within the Commonwealth….We are able to promise our subscribers a sumptuous and profusely-illustrated practical journal, better than anything of its kind yet produced south of the Equator.To enable us to do this, we need the co-operation of all lovers of art; to them we appeal, and we are convinced that our appeal will not be in vain.

It must be remembered that this is not a new or tentative venture, a year’s experience has given us an insight into the support we can confidently expect; and it is because we feel its success that we are encouraged to issue this magazine of “Art and Architecture”.

THE EDITOR JOURNAL OF THE INSTITUTE OF ARCHITECTS OF NEW SOUTH WALES VOL 1, NO 4, OCTOBER 1904

TO LOVERS OF ART, SCULPTURE, PAINTING AND THE ARTS OF DESIGN

1912

In offering to the reading public the first number of The Salon, the Institute of Architects desires it to be made known that the publication will not be a technical journal only, although it will be issued under the auspices of the Institute and will be its official journal.

The chief object the promoters have in view is to foster the interest of cultured readers, and to encourage and assist those who desire to increase their knowledge of the fine arts.The articles will be written by authors well versed in the subjects to be dealt with; the illustrations, except in a few instances, will be by Australian artists; and the letterpress and quality of production will generally be the best of its kind south of the line.

The Salon will be in the best sense an Australian art journal. It is the desire of the promoters that the publication should be a means of interchange of opinion and thought on art subjects by artists and lovers of art in all its various phases.Therefore correspondence is invited and suggestions for the advancement of the publication will be welcomed and acknowledged. I appeal therefore to all architects, to artists in sculpture and painting, and in decorative and applied arts; to artists in black and white; and also to artists in words, to look upon The Salon as their own journal….

Last but not least I appeal to the reading public to support the publication as one which will be a delight to the eye and a medium of education in all the arts.

G. SYDNEY JONES, PRESIDENT, INSTITUTE OF ARCHITECTS THE SALON VOL 1, NO 1, JULY/AUGUST 1912

THE PURPOSE OF “ARCHITECTURE”

1917

“Architecture” is the Official Journal of the Institutes of Architects in the States of New South Wales, Queensland,Tasmania, South Australia and West Australia. It was founded to make the Architects of Australia an articulate force in the body national; to acquaint the members of each Institute with that action the other Institutes are taking on all public and professional questions which have to do in any shape or form with the art and craft of Architecture; to foster the development of a distinctive Australian National style of Architecture; to encourage as far as possible the utilization of Australian materials in our Continent; to obliterate slums and “jerry buildings” and improve the health of our people; and to interest Public and Governments in the Home Beautiful, the Civic Palace Splendid, and the City Magnificent.

“Architecture” will represent the ideals of the Architects of Australia and their Institutes, and fight for them. It will strive to be an educative power, and to foster ideals of Beauty, Health and Utility.

THE EDITOR ARCHITECTURE VOL 1, NO 1, JANUARY 1917

STELLA TOTTENHAM

1950–1954

THE OPTIMISM AND inventiveness of Australian architecture in the early 1950s is documented with special clarity in the quarterly issues of Architecture, edited by Stella Tottenham in the years 1950 to 1954. Interviewed today, Stella Tottenham recalls with characteristic precision the sense of excitement, of ideas crowding in and “things happening” as the period of austerity and reconstruction after World War II gave way to prosperity, growth and a remarkable resurgence of building activity.

The appointment of “Miss S.E. Tottenham B.A., Dip.Ed.” as Publications Manager of the RAIA was announced in the April 1950 issue of Architecture with an outline of her experience in freelance journalism and details of her recent employment in the research department of the advertising agency J.Walter Thompson. The appointment was doubly significant. Stella Tottenham was the first woman editor of the Institute’s journal, and her background in the world of advertising signalled an expanded role for public relations and promotion in the Institute’s activities. Raising the profile of Australian architecture found expression in the content and layout of the journal, together with the organization and promotion of the Australian Architectural Conventions, which began in Melbourne in 1951.

Prior to Stella Tottenham’s appointment as editor, Architecture had been produced by a Publications Board, with Professor F. E. Towndrow and Robin Boyd key members of the editorial team. Although limited by paper restrictions, lack of illustrations and lack of built work, this period saw the publication of important new ideas, such as Professor E. G.Waterhouse’s call for the creation of Australian Landscape Architecture (Oct 1947); George Beiers’ thoughtful review of the fourth volume of Le Corbusier’s Oeuvre Complète (Jan 1948); and Harry Seidler’s incisive analysis of design principles, “Painting toward Architecture” (Oct 1949).

The January 1950 issue of Architecture – the last directly produced by the Publications Board – featured the flat-roofed Hamill House, Killara, by Sydney Ancher. The elegant abstraction of this contemporary work, with its play of solids and voids highlighted in the dramatic contrasts of Max Dupain’s photography, captured the essence of mid-century Modernism in Australia – a clean, spare style which would become the hallmark of Architecture during Stella Tottenham’s editorship, in content, typography and layout.

With the proliferation of new works in the 1950s, Architecture transcended its professional club origins to stand as the “journal of record”. At first, the issues edited by Stella Tottenham were organized around themes. “Canberra” in April 1950, was followed by “Industrial Architecture”, “Prefabrication”, and “Colonial Architecture” in January–March 1951.

Distinguished by Morton Herman’s essay on historic preservation and his account of Blacket’s first church in Australia, this latter issue was clearly laid out to demonstrate the affinity of Georgian proportions, massing and materials with the Modernist project, and Stella Tottenham recalls that Hardy Wilson’s Old Colonial Architecture was always on her desk.

The April–June issue 1951 was an update on “Hospitals”, Australia’s most pervasive modern building type of the 1930s and 1940s. July–September addressed “Public Works”; then, in October–December, Architecture turned to “Houses in Australia” with the long, low Spencer English House by Sydney Ancher on the cover and the first publication of Harry Seidler’s “House at Turramurra” – the Rose Seidler House – as the highlight.

“Houses” provided the theme for all four issues in 1952. The prevailing ethos of the modern Australian house – open and relaxed, with north orientation, light and air, efficient planning, flat roofs, window walls, louvred sunshades, terraces and car ports – was illustrated by examples from across the country, in a graphic format as lucid as the work under review.

Stella Tottenham herself commissioned a house of this type, designed by a member of the Publications Board, Arthur Cozens – a two-level, flat-roofed house sited high above Middle Harbour, built in warm-toned face brick with white timber fascias, sun-break louvres and window frames, an open-plan living space lined with natural timber, a window wall oriented to the view, and a timber deck poised above the garden. The cleverness of Australian small house design was encapsulated here, and was proclaimed in issue after issue of Architecture.

Robin Boyd discussed the emergence of regional variations with articles on the reinterpretation of the “Queenslander” in St Lucia (July 1950), and the skillion-roofed beach house on Melbourne’s Mornington Peninsula (Oct–Dec 1950). The work of Arthur Baldwinson, Roy Grounds, Neil Clerehan, Marshall Clifton, Jack Cheesman, Robert Dickson, Hans Oser,Walter Bunning, Bill and Ruth Lucas affirmed the life-enhancing functionality of the open plan house.

Multi-unit housing was discussed by John Overall in a review of postwar housing in Europe (Oct–Dec 1950). At least two Australian projects demonstrated the possibilities: Aaron Bolot’s one-off work of genius, his ten-storey block of flats at Potts Point; and Frederick Romberg’s two-storey Hillstan Flats ranged along the Nepean Highway at Brighton (Jan–March 1952).

Possibly for the first time in an Australian journal, the international scene was submitted to searching critique in the writings of Robin Boyd. “The New International” (April–June 1951) was both informed and prescient in detecting a new form of decorative Modernism in Italy and Scandinavia. Elements of “New Empiricism” were evident in the Swedish Embassy, designed by E. H. G. Lundquist in association with Peddle, Thorp & Walker, featured on the cover of Architecture in October–December 1953 as winner of the 1952 Sulman Award.

By that time, the magazine itself had departed from a notable tradition. In the first issue for 1952, the title font had been changed from Aldine Roman, with all its Vitruvian associations, to the Bauhaus-inspired exactitude of Futura. Although changed again, two issues later, to a less extreme sans serif font, Architecture had joined the twentieth century.

Several recurrent topics reinforced the technical spirit of the times. Large-scale physical planning and New Town schemes were promoted with enthusiasm. The modern monument was presented as an exercise in structure and functional fit – somewhat portentously in Walter Bunning’s article “An Opera House for Sydney?” (Jan–March 1951) which proclaimed the virtues of the dual-purpose opera house/concert theatre. Structural daring was exemplified in the winning entry in the Melbourne Olympic Pool competition by Kevin Borland, Peter McIntyre, Phyllis and John Murphy, and engineer W. L. Irwin, illustrated with an aerial perspective and a cross section of exhilarating economy and efficiency in July–September 1953. The Rotalactor, the revolving milking plant on the Camden Park Estate at Menangle, NSW by Thomas M.

Maloney (April–June 1953) transformed the dairy into a production-line factory. Clean, light-filled and logical, it seemed to herald a machine-age future for rural Australia.

The last two issues of Architecture edited by Stella Tottenham were produced for the 1954 Australian Architectural Convention, held in Sydney with Walter Gropius as the keynote speaker. The April–June 1954 issue featured a comprehensive photo essay on the history of Australian architecture compiled by Morton Herman, and a nationwide survey of contemporary architecture. The latter demonstrated the persistence of tradition in much non-domestic architecture, countered by a refreshingly direct Modernism in the domestic sphere.

The July–September 1954 issue published Gropius’s conference paper, “Is there a Science of Design?” – a review of the “language of vision” principles which had underpinned his pedagogy and practice since the 1920s. As if to demonstrate the strength of these principles, the July–September issue included a photo history of the Sulman Award since its establishment in 1932, demonstrating the stand-out achievement of Seidler’s “House at Turramurra”. This issue also reviewed the work of Stephenson & Turner, on the occasion of Sir Arthur Stephenson’s RIBA Gold Medal, and therefore linked the new spirit of international Modernism with the practical functionalism of Australian hospital design since the 1930s.

Towards the end of 1954, Stella Tottenham returned to her career in advertising at J.Walter Thompson where she edited the CSR magazine Building Ideas, working with architects and writers such as Eva Buhrich and Peter Willé to present an outstanding digest of Australian and international architecture from 1959 to the 1980s. Her pioneering achievement at Architecture in the early 1950s was to document the transition from traditionalism to Modernism in Australian architecture with a clarity which is still compelling.

STELLA TOTTENHAM SPOKE TO JAMES WEIRICK IN SYDNEY ON 12 AUGUST, 2004.

1962–1972

WE’RE RENOVATING

1975/1977

Architecture in Australia is being renovated.

The core of the journal will remain architectural. But we’re fleshing it out with an array of bright, general-appeal features.

You’ll see: Bigger pages with colour pictures; Regular columns on property, economics and practice management as aids to your prosperity; A pungent column of news and comment; Critical reviews of buildings; Major stories and investigations of importance to the community at large as well as the profession; Regular commentary on art, design and the good things in life; New format and graphic design.

And you’ll notice the name changed to Architecture Australia, in keeping with the sharp, concise style of the editorial content.

Architecture Australia will be indispensable to practising architects and an exciting, provocative magazine to anyone interested in the world around them.

VINCENT SMITH ARCHITECTURE IN AUSTRALIA VOL 64, NO 6, DECEMBER 1975.

This is the first issue of Architecture Australia to come to you from the office of new publishers, Brian Zouch Publications….

On taking over the journal we found ourselves without the advantage of forward copy from contributors, of books for review, a list of Australia-wide contacts, indeed of anything at all that we were naïve enough to expect may have been forthcoming in taking over a journal which had been in existence since 1904. Instead, we found ourselves under accusation from at least one quarter, as some awesome predatory monster, ugly and undesirable in its quest for PROFIT!

We do not suggest that we do not expect to turn this journal into a profit making venture but we say too that we do not see profit as a god.We believe we have an obligation to the readers, to the Institute and to the advertisers to ensure that Architecture Australia becomes the voice of architects everywhere….

We expect this Journal to be as it should be, the very Bible of the architectural profession.

If we are fortunate enough to make some profit along the way we shall be pleased and so will the RAIA as a profit sharing arrangement is a part of the agreement under which we publish….

BRIAN ZOUCH ARCHITECTURE AUSTRALIA VOL 66, NO 1, FEBRUARY/MARCH 1977

IAN MCDOUGALL

1990–1992

LOOKING BACK ON my period as editor of the national RAIA magazine is not easy – I look on that period in my life as a time of immense frustration and ultimately failed effort. It was a time you may remember of the great crash of 1989 when it was rumoured there were more architects driving cabs than working in construction. There was very little advertising revenue for AA. I had come out of a few years as editor of Victorian Architect magazine, attempting to make it into a topical and issues-based magazine, aimed at the practising design offices. AA at this time had a series of guest editors, but was essentially run by the founding partnership of Ian Close (experienced publisher from Rural Press, out on his own) and Peter Johnson (doyen of Sydney architecture and academic circles). It was a little tired.

Like all “free” magazines, it was driven by advertising. In the late 80s its structure had become variously themed issues with about half of the editorial pages devoted to interior design “case studies” and to technical and product news. The latter was really advertorial.

I was a part-time editor, paid a very small stipend, and the magazine had no other architectural or graphics staff. What I had hoped to do was to enliven the publication, get it to speak to the widest sectors of the profession – designers, managers, detailers, etc. The Architects Journal was not out of mind; nor were American magazines such as Architecture and Progressive Architect. I decided to continue the themed issue approach that was in place, a bad decision in hindsight. The effort required to generate single-theme material is a lot harder than the usual “new project review” process that is the staple of architectural magazines. I also tried to open up the range of people normally covered – corporate firms, younger architects, unbuilt projects. For this I needed to free up space – I suggested that Ian Close take the product news pages out and publish a separate magazine; likewise I attempted to integrate or delete the interiors section. I got rid of the Bruce Angle cartoons and also the Discourse issue, suggesting a separate book-like publication for the refereed papers. I got noted designer Michael Trudgeon to redesign the cover and the grid. I employed an assistant with an architectural background, outside the magazine, to review material, chase up copy and generally try to keep up with what was needed to broaden and improve the magazine.

After all this effort for change, what did we achieve? In hindsight not much! After two years I was exhausted and so did something I rarely do, I left before finishing. I am happy with a few modest successes: the issues on the emerging practices, the awards issues with individual jurors’ comments, the coverage of the Hugh Buhrich house, coverage of firms that were outside of NSW and Vic., the issue on city planning and public architecture, even the look of the magazine. There is no doubt that my vision for the magazine as an intelligent professional journal was out of line with the emerging publishing trends epitomized in Monument and AR. And that is where AA went, so I guess I was swimming against the current. With limited advertising and negligible financial support from the RAIA, Ian Close was interested in a newsstand targeting. Surprisingly, as luscious as these newsstand magazines have become, and as successful as they are, they are extraordinarily homogeneous and not a little hollow. In the decade since my sore experience we have seen a decline in the number of smaller specialist publications. Maybe it is time for a rebirth.

IAN MCDOUGALL IS A PRINCIPAL OF ASHTON RAGGATT MCDOUGALL.

DAVINA JACKSON

1993–2000

WHEN THE SEARCH was on for a new editor to replace Ian McDougall in 1992, Architecture Australia was in a serious cyclical trough – stemming from its conception as an in-house freebie and limited revenue at the nadir of the post-1987 recession. RAIA members were complaining about its wordiness, theme-issue limitations and lack of pictorial appeal.

Looking for a new challenge after ten years as an architectural writer/stylist for consumer home magazines, but assuming that the profession’s politics then would require an architect as editor, I offered a strategy report to Architecture Media’s publisher, Ian Close – detailing how to lift AA’s game to a level where it could be sold on newsstands to non-RAIA architects and disciples. I sensed a lack of vision about this opportunity.

That document seemed to impress Close and his board, which then included my late father-in-law, Peter Johnson, who claimed that he took no formal part in selecting me as editor against illustrious rivals. On announcement, there was industry speculation about whether my lack of architectural training would prevent me from performing. As a result of that perception/reality, I avoided writing editorials – deeming that a letter from the RAIA President should (in theory) provide the overviews on topical issues.

However, I’d been circulating nationally around the profession since the late 1970s, my national contact network was by far the best around, I’d paid my dues at Monday Night Talks, had an eye for aesthetics and was confident I could orchestrate a sense of fresh excitement in not only the journal but the industry.

Most crucially, I could see that Sydney’s late-1980s Tusculum Club – architects dressing up in dinner suits to stroke the annointed and shun the unsophisticated – would not be a source of leadership into the twenty-first century. Melbourne’s postmodern and deconstructivist debaters were equally insular in other ways, and both cities were dismissive of new regional stirrings in Queensland (other states hardly on the map). I thought I was well placed to navigate all those scenes and try to knot them together.

Editors need to build around them a supportive team of the best writers and photographers, and to work closely with a talented graphic designer. Carl Martin, a grid, abstraction and colour guy, directed the magazine’s style for my eight years there – outlasting, with his typical equanimity, the profession’s early backlashes against his orange titles rolling over sacred “hero” shots. His assistants, Michelina and Danielle, later added further strength.

In a climate of competition with two other architectural magazines, I was astonishingly fortunate to win the support of John Gollings, who often gave us first rights to publish (for a long time without payment) his brilliant transparencies of the top Australian projects. Other photographers were also generous to us, but without Gollings’ unrivalled reputation, stable of top clients and goodwill, we could not have scooped our rivals as often as we did.

I’m also grateful that most of the elite Australian architects and scholar-writers of the 1990s were generally positive towards my editorial goals. There is a basic desire to support the Institute journal when it has signs of life. However, negotiations were frequently delicate and sometimes difficult about covers, feature titles, page allocations, photography choices, and selections of writers and photographers. Architects – inherently self-focused, factional and in those days mostly locally oriented – were not always impressed with my policies and broader overviews of conflicting debates. Sometimes I would be shunned for failing to meet expectations. Such are the tensions of journalism, at least if you’re trying to think primarily for readers rather than content suppliers or advertisers. Ian Close supported me all the way through.

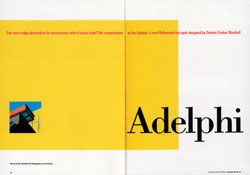

With astonishing luck in retrospect, our first edition of March–April 1993 defined the dawn of not only the 1990s building boom but Australian architecture’s entry into the age of digital representation. Our “scoop” cover story was Denton Corker Marshall’s Adelphi Hotel – including Gollings’ first attempts at Photoshopping the trannies so that they looked as abstract as sixties pop art. Denton and I baulked at this artifice, but we knew our creative tensions with Gollings were historically significant. So we negotiated to run a combination of straight and “enhanced” images. When this appeared, readers were certainly alerted that architecture was now firing out of its neoclassical phase.

During the 1990s, Australian architecture (as a culture) gained real international respect for the first time in our history. More than twenty or thirty firms – as well as several thoughtleaders in the universities – led a media-fuelled ascent of the profession’s performance and stature, nationally and offshore. Surfing these fin-de-siècle, Kennett–Olympic waves was extremely exciting, and my detailed perspectives on the decade are clarified in Australian Architecture Now (Thames and Hudson, 2000).

As well as publishing a constant stream of outstanding architectural works, I began taking on non-editorial projects to expand my education in architecture and city development and to promote (more publicly) the most exciting slices of the Australian scene I was witnessing. After gaining an M.Arch (history and theory) in 1997, and sensing an imminent explosion of foreign attention around the Olympics, I dumped my old mantra that editors should move on after five years and decided to allow my salary to subsidize a three-year burst of timely endeavours. I curated an international exhibition on young architects, subedited Peter Droege’s academic tome on information-age cities (influential on my current thinking), and wrote Australian Architecture Now with my husband, Chris Johnson. I also delivered numerous speeches, articles and interviews and travelled widely.

With that mad workload, however, I no longer had time to maintain my formerly intense interest in the profession’s day-to-day discourse. I was also enthused with digital-age ideas that were either unknown or unpopular with many practitioners. As the internet revolution rolled on, many architects exhibited extreme anxieties or denials about what would happen beyond 2000. As one hint of these nervous tensions, Architecture Australia received about eight solicitors’ threats (none proceeding to court) during my last eighteen months as editor.

As well, I had notorious clashes with prominent Modernist practitioners – letters are preserved to amuse posterity.

Mea culpa for my blind spots. I did not do enough to publish student work, I overlooked some excellent architects in smaller states, the annual AA Prize for Unbuilt Work never gained professional traction, I foolishly resisted the pictorially unsexy agenda of ESD and I missed how some commercial firms were paving the way for worldwide exports of architectural services.

Australia earned more than $60 million in offshore revenue for our architectural design services last year (double earnings in 2000–01, for example) and remains a favourite for international publishers. As one of the world’s top half dozen nations for contemporary architecture, then, we need to address the question: why are we so often absent from the world’s key exhibition event, the Venice Architecture Biennale? Solving that problem is a key goal which could be solved brilliantly if government, architects and interested non-architects pull together on a multi-dimensional plan that’s being hatched around the country right now.

DAVINA JACKSON IS CHAIR OF THE VENICE ARCHITECTURE BIENNALE TASK FORCE, A CRITIC FOR THE SECOND EDITION OF PHAIDON’S 10 X 10 AND A CONSULTANT ON GOVERNMENT URBAN DEVELOPMENT STRATEGIES.