Landscape Architecture Australia: Tell us about the Diepsloot slum upgrade.

Mark Tyrrell.

Mark Tyrrell (Global Studio): Between 2009 and 2011 I worked in the township of Diepsloot in Johannesburg, South Africa. Diepsloot is home to over 160,000 people, over half of whom live in informal arrangements without access to essential infrastructure. I became involved with the project through the Global Studio program, an international “think and do” tank that came out of the United Nations Millennium Development taskforce on improving the lives of slum dwellers. My team initially focused on improving quality of health through upgrading of the physical environment. Over three years our aims stayed the same, but our working method evolved as we tried to grapple with the massive scale of the physical problems along with negotiating a path through power, politics and the violent realities of urban development in South Africa.

LAA: Why did you get involved in this type of work/project?

MT: I am fascinated by cities where formal and informal urbanism overlap and combine in unusual ways and with unexpected results. Cities in developing countries hold the greatest challenges to the designers’ role, as their parts often evolve and dissolve quickly and without plan. This is the urban condition of the future. I wanted to understand how, and indeed if, urban designers could usefully operate within such shifting terrain.

LAA: Can you summarize your team’s engagement process and your role in this project/initiative?

MT: The Global Studio, of which I was a part, initially engaged only with slum dwellers directly on the ground, by spending time in informal communities and undertaking micro design projects with residents surrounding sanitation and personal safety. As years moved on and we gained a more complete understanding of the needs of the community my team began to see the limits of these community-led infrastructure improvements. We moved towards using the urban design process to foster strategic communication between citizens, organizations and city officials rather than looking for built-form outcomes.

Recycling strategies have been implemented.

Image: Mark Tyrrell

LAA: Can you describe an influential person you have met that was key to implementing the process?

MT: In my experience, “implementation” of process doesn’t work well with informal communities. So it was not one person with a grand vision, but rather the many slum dwellers we met over three years in Johannesburg who were the most influential to how the projects unfolded. Process became all-encompassing chaos, where urban design was redefined in the local context as a medium for an exchange of ideas rather than the creation of a frozen plan.

LAA: How has this project/initiative created positive change?

MT: Some physical infrastructure upgrades, such as a pedestrian bridge and improved amenities, were delivered from our urban design work creating positive change, but of course the impact was not enough to improve everyone’s lives. Designers historically favour physical upgrade projects, but in non-disaster situations these are limited in their ability to build the capacity of citizens and often do much more harm than good. Contrary to my initial expectations it was the development of mediums of communication between the government institutions, the gangsters and the slum dwellers that created most positive change.

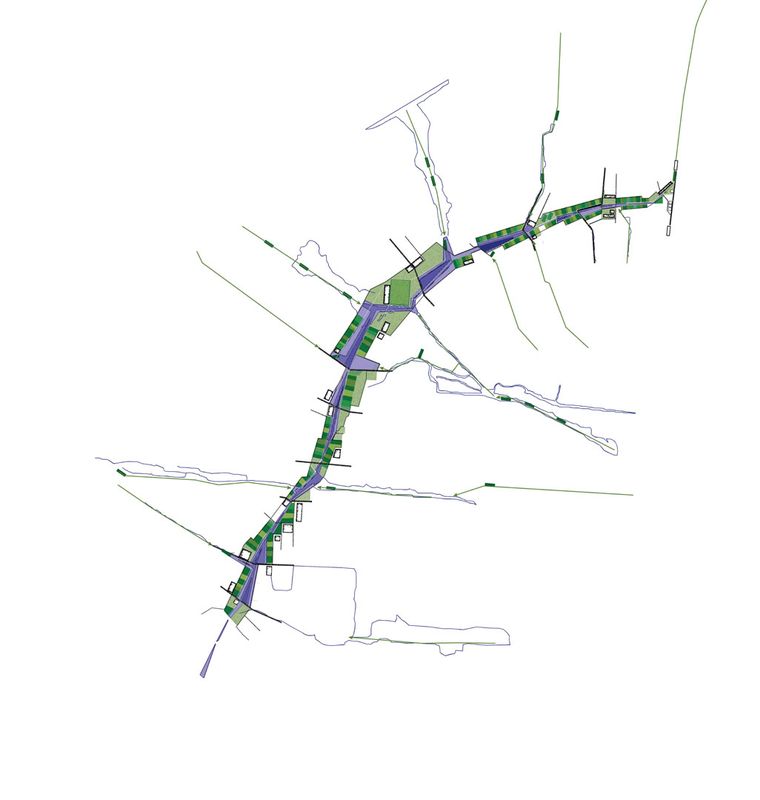

A photograph of the Diepsloot focus area.

Image: Mark Tyrrell

LAA: What is the greatest lesson you have learnt from your involvement in this project?

MT: We are trained to communicate visions, ideas and possibilities in creative ways. I realized that the designer’s abilities to foster dialogue and create greater transparency between different parts of a society are their most useful skills in this type of work. In Africa, visual art and music provide a language that all parties understand. We experimented with the creation of cultural memory of space through art and theatre and linked this to various government infrastructure development schemes. This novel approach taught me a lot about the incredible power of collective memory that a community holds. Urban development needs to occur within and through this mysterious spectrum to deliver lasting change.

Source

People

Published online: 11 Dec 2013

Images:

City of Johannesburg,

Mark Tyrrell

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, August 2013