Looking through the house from the upper garden court to the water.

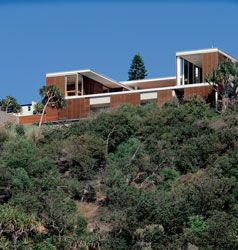

Oblique view of the stepped, layered eastern facade and upper lawn terrace.

Looking across the lap pool to the office wing.

The upper level garden court with specimen pandanus.

Upper reflecting pool with fountain and rainwater spouts. The covered terrace is on the left.

Kitchen and dining areas with the garden court beyond.

The reflecting pool on the lower level, flanked by the gallery spaces.

Looking over the lap pool to the central volume housing the living spaces.

View through the house from the upper garden court. The hovering roof collects the whole together.

The lap pool with bedroom wing to the left and beach beyond.

Standing high on a dune overlooking one of the Sunshine Coast’s most beautiful beaches, the Ogilvie House takes command of its surroundings. It is a reserved and sophisticated building that acquires its presence from the resolution and balance of the horizontals and verticals of its strong asymmetrical geometry. The building breaks from the recent romantic Queensland tradition, in that it is classical in its relationship to the site and in the order of its composition. The house is set solidly down on the earth and complements the natural surroundings through contrast. It is fashioned through the shaping of mass and demonstrates that concrete walls can form as compatible a partnership with the Queensland coastal environment as can steel and timber. In this way it breaks from the lightweight structures, built up from linear elements and capped by the play of pitched and curving roofs, that have dominated Queensland architects’ psyche since Gabriel Poole’s early revolutionary minimalist buildings of the 1970s.

Contrarily, it “hugs the earth tightly”. The building emerges from the architect’s empathy with, and response to, the poetic and sensitive brief of the client, who combed Southeast Asia in search of a designer who could translate their words into architecture.

Kerry Hill’s previous projects, primarily for South-east Asia but also for India, Turkey, the United Arab Emirates and elsewhere, creatively blend a strict modernity with a sound understanding of the regional characteristics of particular locations – both in attitude to design and in building form and appearance. In this, his work resembles that of Geoffrey Bawa in Sri Lanka and these architects share the ability to impart a rich measure of the splendour of place, but with restraint. While the Ogilvie House conforms in being directly in the tradition of Corbusier and even more so of Kahn, it makes few concessions to the Queensland building vernacular. It does, however, make full concessions to Queensland as “place” and the building reveals, in the use of such devices as courtyards, screens and water, that Hill, in terms of the soul if not the body, has drawn on his experiences in Asia to achieve an appropriate response.

The Ogilvie House has a strong sense of materiality. Under its flat roofs, sliced de Stijl-like by east-west vertical planes and by the stepped and layered facades to the east, the building reads as a series of boxes made up of floor-to-ceiling horizontally layered timber screens juxtaposed with sheets of glass and the solid “American Eagle” (a soft earthy tone tinged with olive) planes of the rendered concrete block walls, all neatly delineated by the crisp white banding of facias and frames. The essence of the building lies in the simplicity and generosity of its gestures, be they formal or spatial, and in the clean and precise detailing. The quality of production is high. This is most explicit in the wall surfaces, in the elegantly designed bathrooms, and in the hand-crafting and connecting of the exterior tallow wood: the battens that sheath the windows through ceiling-high screens, and the flooring and siding held in place by more than 40,000 meticulously placed concealed screws and wood plugs. Here the linear element is tamed and trapped into broad sheets. This is a composed building with a tightly limited palette and carefully counterpoised associations: through subtle colours, the play of voids and solids, of marble floors, timber floors and water basins – an uninterrupted orchestration of simple reductive differences.

Hill is a disciplined architect and his architecture is rarely distracted from its principal themes and goals, which for the Ogilvie House were – in the client’s words – to bring about “a sense of simple elegance … a delicate balance between scrupulous simplicity and a feeling of warmth … and a feeling of true peace and serenity, sensuality and refinement”. He defines the “theoretical ambitions” of his practice as “exactitude” and “authenticity” and he sees the plan as “the most unifying strategy of our work”. The plans invariably exhibit a clear logic of use, elevated through their formal arrangements into compositions that are direct and revealing when considered from functional and climatic perspectives, and rewarding in the aesthetic experiences developed from them. The Ogilvie House accommodates not only the recreational and daily living of the family, a caretaker’s unit and extensive car parking, but also serves as a business office and on the ground floor contains a gallery for a fine collection of Australian art. Below ground, preserved from a previous Poole house that stood on the site, is the capacious vaulted wine cellar.

The control of privacy from without, and the control of view from within, is quite masterly. The building is embraced by its sloping corner site which is walled on the landward sides and pierced for entrances at the upper and lower levels. Between these two edges the house connects landscaped courtyards “to create harmony of spaces”: the entry court, which serves the ground/gallery level of the house and gives access via external stairs to a further court for the upper floor offices; the lower water court; the ensuite bathroom court on the first floor; and the upper garden court serving the top entry and guest parking. The courtyards differ in their moods, and with the varied surfaces simply forming stages for single or grouped specimen pandanus palms, the landscaping bears the same lucid signature as the building.

The client requested that the “circulation be joyful, clear and simple”. Entrance from the lower court, through a large pivoting steel-edged timber door, reveals a further space open to the sky and containing the large black slate-lined central reflecting pool of the gallery. The stark emptiness and stillness of this space engenders a sensuous feeling of tranquillity. The pool orders movement on the ground floor together with the north-south directional axis of the eastern wing with guest rooms, gymnasium and exercise deck opening onto the veranda with its sliding protective screens. These open out to the eastern lawns planted on two terraces, supported and edged by precisely steel-edged trays that provide a further geometric foil to the natural landscape as they slice into sloping regenerated fields of dune grasses.

On the upper levels of the house, movement is again directed by sheets of water: this time by the lap pool and the reflecting pools. The subsidiary spaces, bedrooms, offices, library and kitchen are arranged around the large central volume of the principal living space. This is divided by the central double-sided fireplace, but focused on the swimming pool and the ocean to the east. Spaces and openings have been carefully determined to take full advantage of the coastal beauty and the subtropical climate.

Of note are the designs for the principal bedroom and the main office that bracket the swimming pool to the north and south, and in the process shield the interior from prevailing winds. The perimeter rooms on all levels are but one space deep between the exterior and the central volume to encourage cross ventilation, while the house is airconditioned for extreme temperature conditions. At the top of the site to the west, the open space of the street is extended by grassed visitor car parking set at grade and dramatized by the sculptural effect of pandanus trees backed by painted walls.

It is on the upper levels that Hill’s design is most inventive – in the overall volume and in the clever planning which, together with concealed sliding glass partitions, gives rise to engaging ambiguities. What is inside and what is out; what is a room and what is a terrace? What of the kitchen that is and yet is not? Perimeter sliding screens and internal blinds, sheltering the glazed walls, transform the space in terms of its character and the quality of the light brought in from outside “to stimulate the spirit”. The floor is disciplined by a series of parallel rectangular bands that step down from west to east, providing a clear diagram for the spatial order: first the upper court, combining marble, water and grass; then change of level; then marble and water; then tallow wood timbers; then blackbutt flooring; then change of level; then tallow wood deck; then water, finally culminating in the framed outlook over the ocean below that seemingly extends the view to infinity. As with the major composition of the wall and roof planes, this geometry is countered in the other direction, here by minor rectangles such as the long serving bench and a secondary water pool feeding the waterfall to the main pool. The most dominant single gesture is the presence of the hovering concrete roof that resolves the various surfaces and levels into a unity. In times of rain, spouts along the roof edge drop water into the reflecting pool, bringing beauty and sound in a celebration of the weather.

This roof is unusual in Hill’s designs, which more commonly lighten towards the sky.

The space beneath is both static and dynamic, providing large, quiet spaces of respite and affording dramatic linear views, as from the upper terrace first over, then under the large roof, through the building to the sea beyond.

Hill’s previous work in Australia has not had the authority of the Ogilvie House, and there would appear to be little parallel to its design in Australian architecture, except perhaps the use of timber screening devices. Lessons for Queensland architecture are numerous, notably in the use of water. While pools and water features have been used extensively in Queensland resort architecture, surprisingly water’s characteristics of cooling and visual delight have been given but token recognition in commercial and public buildings and seldom appear in residential work. The bold gesture of the placement of the Ogilvie House swimming pool and the extensive integration of water throughout the design are exceptional. The courtyard is also a design device that bears further consideration in Queensland’s climate. Courtyards – while not the major design determinant of this house, as they are in many of Hill’s buildings – nevertheless make significant contributions to the ambience on all levels.

The Ogilvie House is a welcome addition to Australian architecture. With the clarity of its primary forms and its spirit of order, stability and permanence, it presents a refreshing antithesis to the celebrated mainstream of recent Queensland coastal architecture.

Images: Reiner Blunck, Jon Linkins

Credits

- Project

- Ogilvie house

- Architect

- Kerry Hill Architects

Fremantle, WA, Australia

- Project Team

- Kerry Hill, Mark Ritchie, Simon Cundy, Bob Allen, Terry Fripp

- Consultants

-

Civil consultant

Tod Group Consulting Engineers

Landscape consultant Tierra Design

Services consultant Precis One

- Site Details

-

Location

Sunshine Coast,

Qld,

Australia

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Category Residential

Type New houses