Most of the work produced by architects is unbuilt and part of the daily professional dance: concepts, strategies, options, sketches and storyboards. Architectural training places greater emphasis on the building of concepts and ideas than on the practicalities of the built object, yet in typical architectural practice, the success of an idea is most often measured against its built outcome. Of course, as our Instagram accounts attest, many built works are outstanding professional achievements of architectural beauty and some may even hold strong relationships to people, place and time. Yet a built work – even a large and significant one – is, by its very nature, a small set piece in the city, containing highly specific ideas imprisoned by and endlessly tuned to the confines of the project, the client and the budget. Built works are so specific in their successes and so dependent on project context that while they can be influential to other practitioners, their ideas are rarely able to be scaled up to address bigger issues embedded in the built environment. Unbuilt work, on the other hand, remains importantly untethered. It can become the trojan horse in the process of big decisions, embedding, through a strategic design process, big spatial ideas at the scale of the city, a scale that has previously eluded architectural influence.

Unbuilt work has incredible power when it engages the political processes of city governance with the open-ended spatial exploration of the city. Unbuilt work becomes the connector, facilitating through the design process a new relationship between government institutions, stakeholder organizations and individual citizens. This engagement is not passive listening, nor scoring opinions with Post-it Notes, nor ticking off precedent images, but rather collaborating through design. It is leading with compositional literacy and visual poetry, translating meaning into space through compelling spatial narrative and, crucially, connecting people with common ideas through beautiful drawings. The unbuilt work does an enormous amount of heavy lifting in these types of engagements, not as a fixed masterplan solution but as an ongoing provocation of process. The beautifully composed shapes and “big form” of the modernists find new relevance as sacrificial straw men as the designer translates dreams, ideologies and ideas into brief realities, throwing out an exhausting array of fixed futures that can be torn down but never entirely discarded. Design process is about exploring, testing, reviewing and challenging ideas as well as balancing multiple, often contradictory positions. It has a new and important role in urging a static planning system along new paths, attempting to derail city-building practice from its business-as-usual track in order to steer it toward tangents of new thinking. In the context of the governance of cities, unbuilt work is able to connect multiple actors and has the power to make collective change.

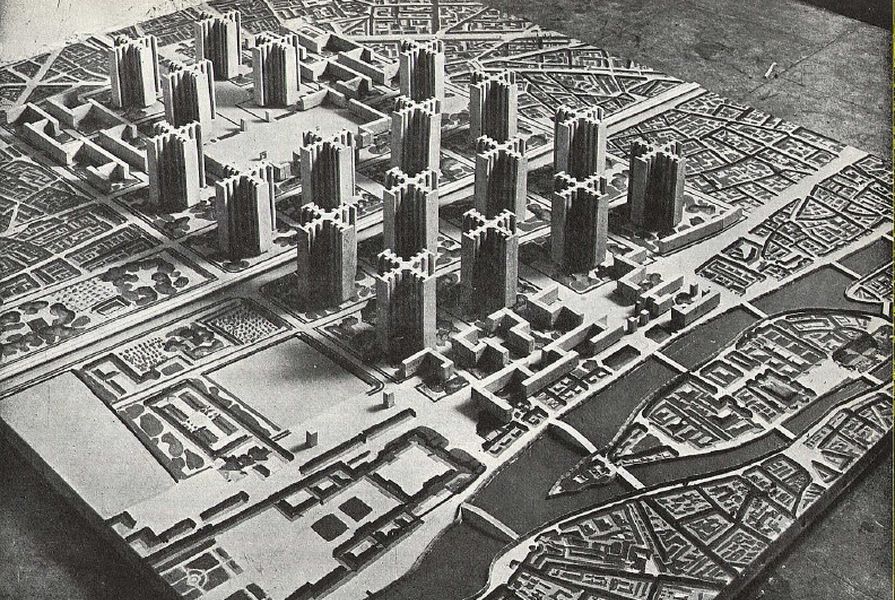

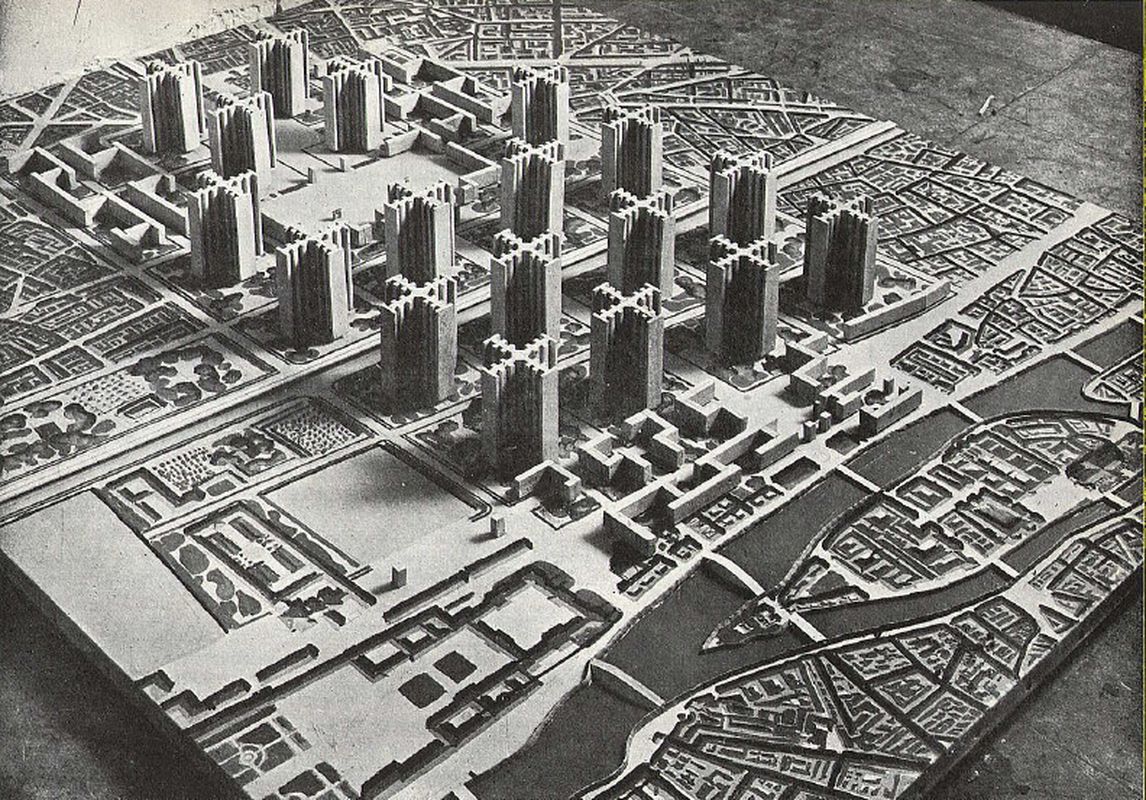

It has taken a long time for strategic, unbuilt design work to find its way to influence. City design theory and method has shifted between the built, the spatial and the strategic poles for many decades and across many projects, responding to changing ideas about the roles of the city and society. In the utopian works of the modernists, there was an experiment to scale up the ideas of small built works to the mega, unbuilt city scale, regarding the solution to social and environmental problems principally as one of form. Who could forget the unsettling early pages of Le Corbusier’s The city of tomorrow and its planning, with characterizations such as “The winding road is the Pack-Donkey’s Way, the straight road is man’s way.”1 Unsurprisingly, form alone could not deliver the social transformations promised by modern architecture. The scaled-up idea of the pristine pavilion in the landscape failed in practice to the extent that many of modernism’s radical experiments have since been demolished, their visionary ideas now deemed failures. The reactions to these failures of modernism were so severe that the role of the designer in the making of the city was essentially disregarded. Architects and landscape architects retreated from their own skill base into citizen engagement and participatory co-design and, embarrassed by the single-mindedness of mega-composition, down-scaled their architectural ideas from the size of the city to that of the single lot. The architect was banished to the purgatory of postmodernism, attempting to build ideas that were far stronger left unbuilt. They left the city to be shaped by the controls of the town planner and the transformative will of the political cycle and big engineering and their contemporary proxies, big data.

In recent decades, the urban design field has emerged, yellowtrace paper in hand, to challenge city planners. Urban design was presented as a sensible, collaborative and facilitatory practice rather than a discipline and it positioned this unbuilt practice away from the radical and experimental avant-garde of the 1980s. The profession touted best-practice ideas and European precedents, reviving the lost history of active edges, walkable streets, human scale, fine grain, civic connectivity, public transport and democratic public space. Ironically, the mixed-use collages of urban design – which revealed echoes of the superimpositions of postmodernism – began to provide more answers at the city scale than they had in built form, effectively exploding the zones of the city planner. But despite its admirable themes and its creative pioneers, urban design has been undone by the prevailing urban design method: the motherhood vision statement, two-phase masterplan and design principles have quickly became formulaic and, in fact, anti-design. The consequential descent back into routine was driven by the confines of the project brief, which once again proved to be too fixed in its masterplan requirements and arriving too late in the political process to effect new ideas. Urban design has generally failed to harness the power of the unbuilt. The vagaries of principles and the static nature of the masterplan have too often been unable to inspire broader action or outcomes over a flexible timeframe beyond the initial built work or funding cycle they are produced to justify. From the modernists to the participatory co-designers, and from the town planners to the urban designers, the lack of inspiring, flexible, adaptive and community-championed design thinking at the front end of decision-making has left our cities placeless. We cannot be surprised, then, by the resultant mania for placemaking in everyone from the city mayor to the real estate star, even in the storybooks of the new urbanist. The turbo-gentrification machine of civic branding has filled the void of spatial thinking and begun to close down our cities to banal narratives creating place, as Disneyland creates place.

The problems that face humanity today have emerged from an overwhelming web of environmental, social and political complexity far beyond the sum of a city’s built fabric and beyond the grasp of the feelgood narrative. Big design problems are larger than one site, one building, one place or one solution. Cities, it turns out, are as much social networks as they are bricks and mortar and, in current times, they are evolving and changing with a speed unseen in the past. Witness the emptying of cities during the COVID-19 pandemic, their CBDs turned into sudden relics as their unbuilt activity transitions instantly online. It is in this context, and in the contemporary delirium of new “place”-focused professional titles, that unbuilt work has begun to find its footing again.

Unbuilt work is bringing the core skills of architectural thinking and visionary ideas back to the big end of town. Crudely, this new process could perhaps best be described as a kind of mashup of utopian modernism and practical participatory planning and design, set inconspicuously beneath the general umbrella term of “strategic urbanism” or “strategic framework.” How did the unbuilt exploration find its way to the top? For this we should thank the placemakers, for they have managed to sell to the highest levels of government the idea that it is possible – easy, even – to create meaningful cities, a feat that the architecture profession could never achieve because it was so weighed down by its cumbersome built realities. But while placemakers have produced calendars of events, their limitations in connecting this events software to the spatial hardware of the city have been quickly exposed. This has created an appetite for a new type of strategic unbuilt work, spurred by a new optimism – or perhaps the first stages of a new desperation. Whichever it is, massive flexible strategies for change are in high demand.

The masterplan is officially dead and the more flexible approach of the “framework” has taken its place. Frameworks provide room and licence to design and, through the design process, enable spatial visioning to be linked in a new way with the complex social, political and cultural reality of the evolving city. Unbuilt work is key to these frameworks, offering a form of advocacy and sponsorship of ideas in larger strategic planning contexts, especially with government. An exploration of the unbuilt has become a language used by all stakeholders in larger conversations to move beyond the usual collaborative vagueness of the “middle ground” masterplan. The unbuilt work is instead a vehicle that captures and sustains big and unruly ideas. Higher and better outcomes are retained, even when they are impossible or contradictory. Multiple versions of the future are captured and ideas live on, to be either actioned as conditions evolve or revisited simply to provoke re-engagement as that important yet so often overlooked part of the city – its people – changes over time. Unbuilt work becomes a steward or caretaker of these ideas and values and, through the process, has unlimited power to change minds, imagine new directions and embed big ideas into the DNA of the city. This way of working with the unbuilt city offers the ultimate tool of scalability that has eluded architecture for so long: to scale down to the built work rather than up from it, creating powerful catalytic projects and connecting political sponsors to the spatial and social dimensions of the city, untethered from the confines of time.

1. Le Corbusier, The city of tomorrow and its planning , originally published 1929 (New York: Dover Publications, 1987), 12.

The experimentation, speculation and invention of unbuilt work is celebrated in the AA Prize for Unbuilt Work. Entries to the 2022 prize close 27 August 2021.Source

Discussion

Published online: 23 Aug 2021

Words:

Mark Tyrrell

Images:

FLC/ADAGP

Issue

Architecture Australia, January 2021