BETWEEN THE EVERYDAY AND THE SYMBOLIC. ELIZABETH FARRELLY CONSIDERS JAMES JONES’S PREMIATED SCHEME IN CANBERRA’S 2001 CENTENARY OF FEDERATION PLACE COMPETITION.

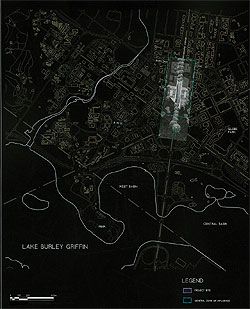

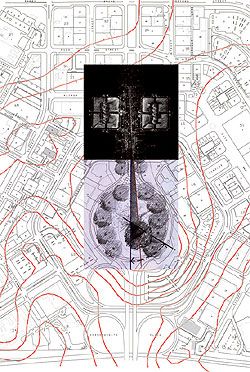

James Jones’s stage 1 entry for the Centenary of Federation Place competition. Plan showing the proposal in Canberra’s urban context.

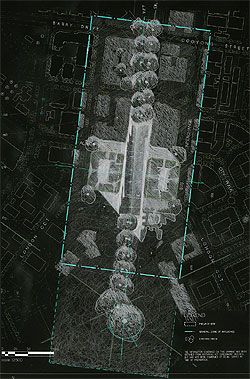

Site plan, with the “landed shed” between the Sydney and Melbourne buildings on Northbourne Avenue.

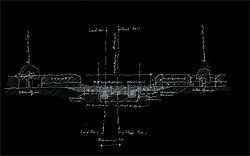

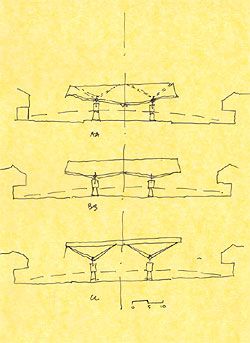

Cross section showing spatial relationships.

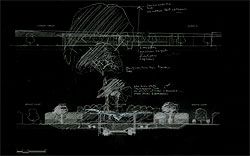

Upper drawing: longitudinal section, looking towards the Melbourne Building; lower drawing: cross section looking towards City Hall.

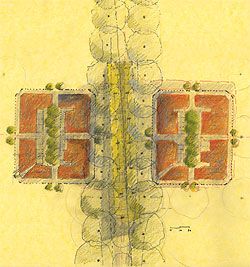

Drawings from the stage 2 entry. Precinct plan.

Plan of “The Place”.

Sections at centre of “The Place”.

Column plans. Stacked glass columns sit on stone and water tablets. Each tablet represents the location of the states and territories and the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

CANBERRA IS AUSTRALIA’S front room. No-one goes there, really, except great-aunts and official visitors. But we needed somewhere to keep the cut crystal, the china figurines and the pointless gifts, and Canberra is it. Canberra is our national display cabinet, our airless trophy room of monument and metaphor, intended inter alia to free the rest of the country from obligation in that regard. Beyond the regulation unknown soldier, thanks to Canberra, we-all don’t got to worry ’bout higher meaning.

Canberra, on the other hand, is pretty much a hundred per cent in the symbolism department. From Burley Griffin’s XXL triangulations to the memorial plethora encrusting every spare axis, it’s metaphor all the way. And that’s the good bit. Outside the federal triangle things get really blousy, as expedience replaces symbolism and monumentalism vanishes under roads, grass and surface car parks.

How, then, to manifest the threshold between the two worlds, the ornery and the symbolic? This was the conundrum at the heart of an urban design competition held in 2001 by the ACT Government (under Centenary of Federation auspices) for the catchily-named Centenary of Federation Place. (That works, for sure, as in “meet you at Centenary of Federation Square”.) It was a competition half-won but never published, never built. A competition where the brief itself, arguably, rendered James Jones’s premiated scheme unbuildable.

The site was that piece of Northbourne Avenue that runs between John Sulman’s gracious but long-neglected Sydney and Melbourne buildings. And, neglect notwithstanding, these two colonnaded dowagers are still among the most welcoming objects in Canberra: sentinels at the civic gate, twin relics of Burley Griffin’s dense municipal dream. Here on in, they seem to imply, civilization is imminent, if not actually present.

Symbolically, then, the choice of site made sense. Not only is Northbourne the main road in from Sydney and Melbourne, but where else does Australia make plazas, except on major thoroughfares? It’s the same old entry-square-as-shoot-through-space habit that produced, for example, Sydney’s Taylor and Whitlam “Squares” - clearly flagging our reflex denial over being here in the first (second) place.

In geometric terms, the site is less apt. Northbourne Avenue is one of Canberra’s ongoing confusion-generators, since it leads you into the federal triangle not on-axis (Parliament House looming grandly on the horizon, blah blah) but obliquely, along one of the triangle’s sides. This by itself would be enough to render Canberra’s geometry illegible, even if scale allowed such reading. And then of course there’s the thoroughfare thing: how do you establish a “distinctive, distinguished and memorable space that may be … used for community celebrations” on a six-lane interstate highway?

The brief called, moreover, for a deal of design complexity. This on-road civic space must also symbolize Federation, terminate the avenue, create a threshold, accommodate a “pedestrian plaza and shared use zone”, embody cultural diversity (within some as-yet-unspecified budget), establish City Hill as a destination (not a traffic roundabout) and “express [for Northbourne Ave] a communal character as distinct from its arterial road image”. It was always going to be tricky.

The further challenge was to design such a threshold-cum-plaza-cum-monument-cum highway so that it might hold its own in so monument-saturated a town, while retaining something of a genuine Australian feel. This in itself is a conflict, given the traditionally ponderous and introverted nature of monuments and the wide-open-endedness we customarily associate with this worn-down continent.

So it is no surprise that Jones, whose work has a distinct tendency to elegant-sheddery anyway (in the same year he won the Queensland Gallery of Modern Art competition for Architectus with a shed of major proportions), erred on the side of Australianness. In Jones’s own words, his proposal for COF Place, also produced under the auspices of Architectus, was just “a landed shed amid a few gnarly gums”. Though of course it wasn’t quite that simple.

The “landed shed”, set directly between the Sydney and Melbourne buildings, is a louvre-protected, glass-roofed pavilion on twelve spindly legs of stacked, steel-centred glass. The roof begins, at its northern end, as a steep ravine-section (or valley gutter) before morphing as it rises to a near-flat shallow drape that salutes City Hill and Parliament House.

Each leg of the pavilion is artist-etched with abstractions emblematic of a state or territory, drawn from each constituent flag. Each sits on a stone-and-water tablet set into the ground and composed according to a further abstract rendering of that state. Tasmania, for instance, as island state, is a stone rectangle surrounded by water, while the Northern Territory has a great rectilinear bite out of it and the ACT centres on a small rectangular inland lake.

Jones’s “gnarly gums” substitute for the brief requirement of “eleven flagpoles” - again to represent each state and territory plus the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and the Commonwealth. Jones, reacting against what he sees as the flagpole’s colonial overtones, proposed instead to encircle City Hill with ten eucalypts of varying species. At their centre, on the eccentric hilltop once earmarked by both Burley Griffin and John Sulman for City Hall, a 100 metre Eucalyptus regnans (or mountain ash), the world’s tallest flowering plant, would become the Australia Tree. (Fortuitously, the hill sits a few degrees off the Northbourne axis, so even the giant regnans would not obscure the incomer’s view of Parliament House.)

The third primary element of Jones’s scheme - possibly that responsible for its eventual rejection as “unrealistic” - was underground. Jones proposed not only the undergrounding of Northbourne Avenue at this point, but the establishment of a transport interchange to accommodate the Very Fast Train from Sydney and Melbourne as well as a more localized light rail.

This idea, enabling commuters to embark at Melbourne or Sydney Central and disembark at Civic, not only enhances the proposal’s threshold symbolism but also resolves the incompatibility between highway and plaza. The jury, however, chaired by Betty Churcher AO and including architects Peter Tonkin and Michael Jasper of the National Capital Authority, felt it was crazily unrealistic.

Perhaps they were right. Perhaps the thing was never serious in the first place, since the brief makes no mention of either budget or federal government support, both essential for even limited realization.

Jones, perhaps divining all this, offered therefore a shorter-term proposal to pencil in the underground elements and establish, in the meantime, a secondary cross axis linking the internal courtyards of the S & M buildings at their halfway point. These courts, although handsome in principle, are currently used for garbage and servicing. Jones’s approach was to re-strategize the servicing, landscape the courtyards and establish that exceedingly rare Canberra entity, a pleasurable pedestrian experience.

Nothing doing, however. Jones says he was called by the ACT government and congratulated on his win. He was even paid for his work. But there was no letter, no announcement, no job and no building. Meanwhile, of course, the usual to-Burley-Griffin-or not-to-Burley-Griffin arguments continue, with Canberra’s planners proposing densification (several thousand new residents along Constitution Avenue, for example) and her NIMBYists rhythmically rejecting same.

And this, perhaps, is where the true symbolism lies. For just as government must generate apparent and ceaseless motion to disguise a deep fundamental stasis, Canberra the town relies on a similar perma-inertia - the constant birthing and killing of urban plans, strategies and competitions - in order to sustain undisturbed the purposeless but constant motion of its Brownian front-room dust motes.

ELIZABETH FARRELLY IS A SYDNEY-BASED ARCHITECTURAL WRITER AND CRITIC.