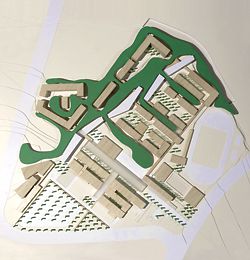

Winning entry by Kerry Hill Architects in the first competition, for the campus masterplan and Main Building.

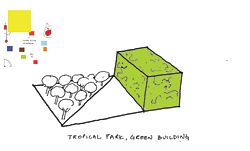

Entry by WOHA to the first competition, for the campus masterplan and Main Building.

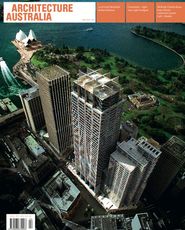

Winning entry by Johnson Pilton Walker in the second competition, for the Science and Engineering Building.

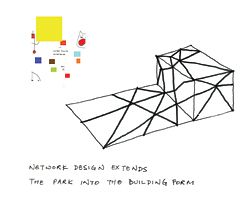

Entry by Bligh Voller Nield in the second competition, for the Science and Engineering Building.

A campus cancelled. Geoff Hanmer outlines the process and proposals for UNSW Asia.

In May 2007, the early works programme for the new UNSW Asia campus at Changi, Singapore, was complete – 846 piles were in the ground and bulk earthworks were finished, including two “rainforest gullies” that were a key part of the Kerry Hill Architects masterplan. The contractor was ready to start construction of the Main Building, designed by Kerry Hill Architects, and the Science and Engineering Building, designed by Johnson Pilton Walker. A lot of hard work by the whole project team meant that stage 1 was within its budget of SG$170M and on time. There was only one problem: on 23 May 2007, UNSW announced the closure of UNSW Asia, less than one semester after it had opened at a temporary campus in Tanglin. The dream of the Changi campus was dead.

The cancellation of UNSW Asia ended one of the most ambitious architectural programmes contemplated by an Australian university. It was the most heartbreaking of architectural hard luck stories, but what the project team did and how they did it provides a significant legacy.

The heart of the project was the aspiration to build a sustainable campus in Singapore for up to 15,000 students and to make it engaging and special. The campus masterplan was to incorporate everything that UNSW had learned redeveloping its Kensington campus over the last fifteen years. In addition, stage 1 included a research project to examine campus design, which was to feed into the brief. The campus was to have a heart and soul from day one, and it was to be designed not to look like a campus under construction, which would, in fact, be the case for ten or even twenty years.

The result promised to be a great campus. According to Glenn Murcutt, who was one of the assessment panel members for the first competition, the Kerry Hill Architects design for UNSW Asia, with its Great Verandah, was likely to create “one of the finest campus environments in the world”. The Great Verandah symbolized the whole campus; it reconceptualized a campus gathering space, protected from tropical sun and rain, relying on fans for air movement. In addition to being a great place, it would make the best of the Singapore climate without airconditioning.

In 2004, UNSW signed an agreement with the Singapore Government to open a campus in Singapore. This stipulated that UNSW had to occupy a new campus by 2010, and work on the choice of site and the brief for the campus began almost immediately. UNSW selected a 17-hectare site in Changi, a fair way from the centre of Singapore, but within 400 metres of an MRT station – it would have been the only university campus in Singapore served by the MRT. Stage 1 was set to provide accommodation for up to 3,500 students plus 300 staff.

After considering a number of options, including design and construct, open competition and direct appointment, UNSW decided to select architects by holding two invited design competitions, both supported by stipends for the participants. UNSW considered that a design competition would add considerable value to the projects. This is borne out by the quality of recent work on the Kensington campus, which includes the Sulman-Award-winning Scientia by FJMT and distinguished buildings by other architects, including Lyons and Bligh Voller Nield.

The first competition was to select an architect to produce a masterplan and to design the main campus buildings. The second was to select an architect for a science and engineering building. There was a deliberate decision not to have one architect produce all the buildings in stage 1, but to accept that any campus completed over a period of twenty years would be a work of many hands, and that variety in style and approach would enliven the result if properly integrated by a masterplan. It was also recognized that the unifying element of the campus would be its (tropical) landscape and that the essence of the campus would be found in the spaces between the buildings and not in the buildings themselves.

The main reason for competition by invitation was time, but cost and the quality of the selection process were also factors. Although competitions by invitation are often criticized, particularly by architects not on the short list, they do tend to produce more consistent solutions than open competitions. Invitation also avoids what might be called the Bastille Opera effect, where an untested architect is unable to deliver on the promise of their competition scheme. Naturally, the quality of the result depends on the quality of the short-listing process.

The first competition was preceded by several months of research that led to a competition brief. This involved investigating existing tropical campuses, the consultant and construction industry in Singapore and the social, economic and political context of Singapore and the region. It also involved a mammoth short-listing effort that initially involved over one hundred architectural practices in Australia and Asia and many rounds of meetings with the senior management of UNSW. Eventually, twenty-two firms were short-listed and then whittled down to two lists of five, who were invited to participate in the competitions. Selection criteria focused on the design ability of the firms, their capacity to deliver work in Singapore and their ability to respond to the design challenges posed by a cross-cultural institution and the climate.

A number of Australian universities, notably Monash, RMIT and Curtin, had already constructed campuses in South-East Asia. In Malaysia, Monash had partnered with a local developer to produce a campus that looked like a shopping centre (the new one is a slightly different story). In Ho Chi Minh City, RMIT had built a tilt-slab building in a country without a tilt-slab construction industry; and in Miri, Curtin had built in fair-face brickwork to match Curtin’s campus in Perth, using materials and trade skills almost completely unknown in Sarawak. This was interesting; what were these universities trying to do, and what had they achieved?

The answer was complex, but the guts of it was that Australian institutions seemed to have missed the opportunity to create environments that addressed the local climate, or that created a nuanced response to the cultural issues involved in providing Western education in an Asian country. Either the campus said nothing, or it was a resolute statement of how different Australia was from the host country. The RMIT campus in Ho Chi Minh City was shocking – a slab of Melbourne architectural culture dropped into a rice paddy – and there was nothing to suggest any sense of irony.

Searching for satisfying examples of university design in the tropics in general and in South-East Asia in particular proved difficult. Older buildings, such as the University of Malaya, now the Bukit Timah campus of the National University of Singapore, were built in architectural styles that not only acknowledged the climate, but worked with it to create buildings that were usable without airconditioning. However, in the post-colonial era after WWII, most of the lessons learned about climate responsiveness were overturned in a rush to adopt modernistic architectural styles that the newly independent Asian nations used to express their economic and social progress.

Many of the postwar commercial and institutional buildings relied completely on airconditioning to make them habitable, and they were often devoid of any architectural elements that would differentiate them from buildings in Western countries. The campus of Nanyang Technological University (NTU) is a good example. Built in the early 1980s after a design by Kenzo Tange, it could, from a distance, have been built more or less anywhere in the First World, which was, of course, the point.

Possibly the most interesting example of tropical campus design is Geoffrey Bawa’s University of Ruhunu near Matara in southern Sri Lanka. The campus is a piece of architectural brilliance, but due to its location, and the fact that it uses a palette of traditional materials, it seems to have failed to fire as a source of inspiration for the design of other universities.

Singapore is economically very different from the rest of South-East Asia, although it has other things in common. Roughly speaking, Singapore has a GDP per head comparable to that of Australia, over three times that of neighbouring Malaysia, but it has a Gini index (a measure of income inequality) that is among the highest in the world. Like Malaysia, Vietnam, Myanmar and Cambodia, it is a one-party state.

In the 60s and 70s, Singapore had a group of strong designers, including Architects Team 3, producing buildings that drew on overseas ideas but were also self-assured in their local character. From the 70s, government policy supported an approach where an internationally recognized architect provided a design with Singaporean architects in a documentation role. The intention was to raise the profile of architecture in Singapore, but the policy led to architectural disaster. In over twenty-five years, this approach has failed to deliver any building with an international reputation, but it has done a lot of damage to local design skills.

UNSW was determined to avoid the obvious pitfalls. First, a number of younger Singaporean firms were invited into the short-listing process in their own right, including WOHA, who were eventually selected to participate in the first competition. WOHA is one of the most interesting and capable firms in Singapore, and they draw their inspiration from a rich variety of Asian and Western architecture. Their residential work is notable for a return to the workable natural ventilation techniques of the traditional Singapore house, albeit in a very different context. Second, any association between Australian and Singaporean architects had to be an association between equals, with both firms supplying significant expertise.

Kerry Hill Architects, the eventual winner of the first competition, was invited to participate only after UNSW had been convinced that an architect best known for his hotels could produce a campus. In fact, the sort of campus UNSW began to imagine in the competition brief was more like a resort than a traditional campus, so Kerry Hill’s style and experience were absolutely relevant. The brief identified the function of a campus as being to bring people together, to give them places to meet and interact and also to provide opportunities for contemplation and reflection – all very evident in Hill’s work. The idea of campus as a resort (a place where people want to go) rather than campus as a workplace (a place that people have to go) became crucial to the project. In many senses, Kerry Hill was the natural choice for UNSW Asia, a highly awarded Australian architect living and working in Singapore.

From about halfway through the first competition, it was obvious that Hill was trying very hard. He had (he said) never entered a competition before, but he committed significant resources to the process. In the end, the selection panel was more or less unanimous in choosing the Kerry Hill Architects scheme. The images were seductive, but the masterplan, the Main Building and the Great Verandah all worked. The decision to drain the site using habitat-creating rainforest gullies was seen as a masterstroke.

Interestingly, only two masterplan schemes fully embraced tropicality – Kerry Hill and WOHA, both located in Singapore. The Australian-based architects, particularly Bligh Voller Nield, created schemes with strong images, but the capacity of these schemes to work in the tropical climate was heavily questioned by the assessment panel.

For the Science and Engineering Building, UNSW wanted an architect with experience in laboratory design, but ended up with two. Johnson Pilton Walker, the winner of the second competition, eventually chose to work in association with Architects Team 3, a local firm that was one of the participants in the second competition. Although the Science and Engineering Building was seen as a low-key counterpoint to the Main Building, it was technically demanding, and the JPW solution was simple, direct and in tune with the masterplan. The BVN scheme was highly regarded, but it did not fully conform with the masterplan and was assessed as being likely to breach the budget limits. It was rejected with regret.

Geoff Hanmer is managing director of Arina, an architectural consultancy for the higher education sector. He was the design project manager for UNSW Asia from its inception until 23 May 2007, and the author of the brief.

2008 AA Prize for Unbuilt Work. Entry details in the May/June 2008 issue of Architecture Australia.

First competition (round one) masterplan and Main Building

Bligh Voller Nield

CM +

FJMT

Kerry Hill Architects

WOHA

Second competition (round two) Science and Engineering Building

Architects Team 3

Bligh Voller Nield

Jackson Architecture

Johnson Pilton Walker

Lyons

Key project staff

Paul Turner, UNSW Asia Project Director;

Tony Inglis, UNSW Asia Project Director;

Graham Parry, Assistant Director, Planning and Development;

Ang Chee Meng, Project Manager.

UNSW Asia key stakeholders

Professor Greg Whittred, UNSW Asia President;

Professor Bruce Milthorpe, UNSW Asia Deputy President;

Maria Spies, Director of Organisational Development, UNSW Asia.