The relaunch of the AA Prize for Unbuilt Work is timely, occurring in the midst of a global pandemic that is expected to cause the greatest economic recession since the Great Depression of the 1930s. Recessions can be tough periods for architectural practices, particularly when it comes to getting designs built. I recall my early years when twice I graduated into recessions: first the 1987 stock market crash and then again in 1991 during prime minister Paul Keating’s “recession we had to have.” As a result, although I was working, I didn’t experience having a project built for 10 years after graduation. Yet that time was formative in terms of thinking, development of ideas and international study.

Unbuilt work, I believe, is critically important to all practices and is not just the domain of emerging or radical practices. Unbuilt work is at the core of what it means to practise architecture. It influences the development of one’s architectural ethos, the honing of an “ideal” design process and the ability to explore ideas in a non-judgemental forum. Further, unbuilt work provides the opportunity to engage in the civic responsibility of city-shaping, representing the public interest and the common good.

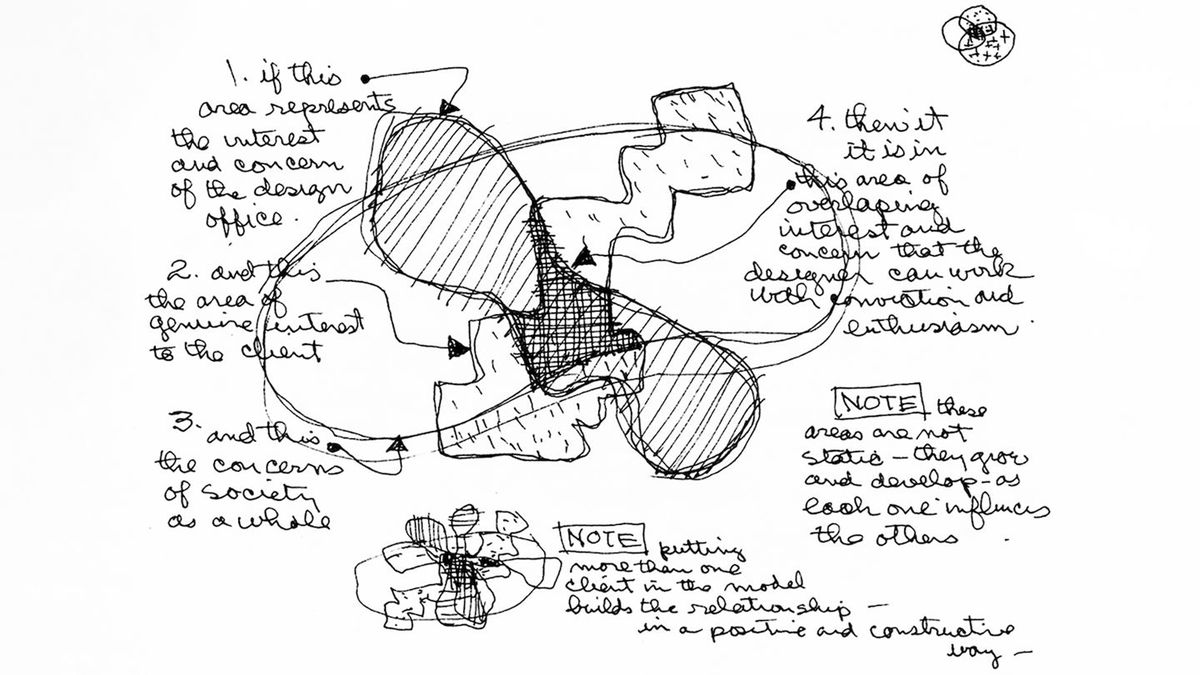

Charles Eames’s 1969 diagram of the design process shows where the needs and interests of the client, the design office and society can overlap.

At Bates Smart, the majority of our unbuilt work comes from either competitions, where it is paid design work and usually for developers, or our city-shaping visions, which are internally generated and unpaid. Visions are speculative and carry the civic responsibility of public interest and the common good for the invisible client of the public, while competitions have quite specific briefs prepared by the developer and usually approved by a local government or state authority. While both of these forms of unbuilt work are undertaken without the client present, this unfettered approach does not, in our experience, lead to the unrealistic or “wild” design outcomes that are sometimes feared by developer clients.

The value of competitions and that of visions differs significantly. Competitions provide the relatively rare opportunity for the architect to control their design process, unhindered by weekly reporting to clients or project managers. Released from a managed process, the architectural practice is free to balance formal expression, public interest, city-making and ideas simultaneously with commercial reality, creating a truly integral design response. Charles Eames’s sketch of the design process comes to mind, in which bubbles representing the interests of the design office, the client and society overlap, with the “area of overlapping interest and concern [being where] the designer can work with conviction and enthusiasm.” 1 Inadvertently, the competition format has provided our practice with the time and intellectual space to hone an “ideal” design process to such an extent that, internally, we have started to critique our design process for commissioned works. We find ourselves asking whether we are delivering the same thorough process to our clients.

Unbuilt work from competitions also presents our practice with the opportunity to explore ideas and innovations without the scrutiny of commercial pressures. Ideas can be freely integrated into the thinking process, allowing the architect to explore and develop thoughts without the constant necessity to commercially justify them. Untried ideas for building materials, systems and expression can be explored, with the freedom to integrate or discard them at any time. For a large practice, this can provide a rich source of research and development, leading to genuine innovation. Some ideas that have arisen in design competitions include facades that filter air and noise, apartments that are fully flexible for future modifications, offices with “sunglasses” for glare and biophilic offices with flexible mass timber social spaces.

We view unbuilt competitions as valuable in the development of our culture and design process, rather than simply being a cost for the practice. They are short and intense periods of creativity, requiring a “cycling through” of many ideas in a compressed period of time. They are, to borrow a phrase from the industrial design industry, a form of rapid prototyping that encourages the speedy production of half-thought-through ideas. We encourage design teams to “fail fast and fail early,” leading to a broad and rapid exploration of ideas. The speed of competitions also leads us toward conceptual clarity, whereby ideas are distilled to their essence in a condensed period of time.

This combination of an unfettered process, condensed creativity and freedom to explore ideas ultimately has the value of developing and refining a practice’s architectural approach or its ethos. The ethos of a practice is, after all, the ultimate value it offers to its clients and, in this sense, unbuilt work is a fundamental basis of practice. In order to ensure we can continue to engage in this important practice, we attempt to manage the costs of competitions such that, ideally, the fee covers the labour cost. While there is no profit or overhead for the practice, this approach allows us to view competitions as a form of paid architectural research.

Separate to competitions, unbuilt work provides a means by which our practice has undertaken a series of pro-bono city-shaping urban visions for Sydney. These visions step into a governance void, where there is an absence of an overarching authority in charge of city-making. They are uncommissioned – and un-commissionable – existing in the inter-agency territory between and across government authorities. They are personal passion projects that, we believe, are a vitally important form of architectural advocacy and make a contribution to the public and civic debate about cities. More than a personal indulgence in city-shaping, these projects further the practice’s interest in transformative city-making while being a subtle form of brand positioning.

Urban visions reposition architects to take a visionary role in addressing the humanitarian challenges of the twenty-first century, including the problems of rapid urbanization, the climate crisis and urban inequality. This enables us to engage in big-picture thinking for cities and participate in a civic dialogue about the future of cities beyond the boundaries of everyday practice. They are a vehicle for us to use our professional design skills to think laterally, solve problems and present ideas for the future of cities, representing the value of design-led thinking in city design and posing as a type of “design-led optimism” for the future. They are also a form of architectural activism, representing the ethics of our practice in promoting the value of design, civic responsibility and city-making to the public. Distinct from criticism, these visions are positive or optimistic critiques of urban conditions and political decision-making that hasn’t considered its broader city-shaping responsibilities.

So, what is the value of unbuilt work to practice? In our experience, it has proved instrumental in the development of an approach to design or an architectural ethos, and in honing an “ideal” design process free of a client-led agenda. It gives architects the ability to explore ideas in a non-judgemental forum, freed from commercial critique, and to engage in a civic responsibility for city-shaping, representing the common good and the needs of society – our invisible clients – in the design process.

If this sounds a lot like the reason many of us became architects in the first place, one could conclude that the value of unbuilt work is fundamental, or essential, to practice. And although many architects perceive having their designs realized as one form of success, perhaps Winston Churchill was right when he said, “Success consists of going from failure to failure without loss of enthusiasm.”

Source

Discussion

Published online: 20 May 2021

Words:

Philip Vivian

Issue

Architecture Australia, January 2020