“There is almost a complete absence of contemporary discourse on architecture’s relationship to the general condition of housing in Australia.”1

Our communities are becoming much more diverse, unsettling the traditional order of housing in Australia’s main cities. The National Housing Supply Council has estimated that seven out of ten households can now be termed “non-traditional.” While traditional two-parent households will increase by 20 percent over the next two decades, the number of couples will rise by 36.7 percent and the number of single households will soar by 63.7 percent, with the sixty-five-plus age group growing the most in Australia. Of these, one in five will be single when they retire and they will be mainly women.2 The dramatic increase in the aged population will also require new forms of housing beyond the conventional corralled “aged or retirement” models.

A further and no less significant influence on housing is the geoeconomic shift now underway. Attracted by a stable political system, relatively low investment barriers and quality physical environment, increasing numbers of people from South-East Asia and China are seeking residence and/or investment opportunities in Australia.

As a consequence, the relationship between architecture and housing will now be amplified through the provision of higher-density housing models throughout major urban centres, inner-city locations and even fringe areas, meeting demands for this rapid increase in different household configurations and cultural diversity. Architecture will have a direct role in housing much more of our population than it has in the past.

For the architecture profession, this will require a greater level of research and design expertise than what is currently evident in practice. The provision of housing in Australia has not significantly changed since white settlement, yet cause and effect precedents are valuable in order to identify effective pathways.

In Melbourne, multi-residential architecture is full of turn-offs, short sprints and long runs of both type and frequency. Of relevance to current output is the modernist movement of the 1930s and 40s, when Melbourne witnessed the construction of a new generation of apartment architecture – a period in which architecture influenced housing design. Writing at the time, Robin Boyd identified an open “spatial composition” of “confinement and release” as the average house size was “forced to contract to compensate for rising costs.”3

Moonbria apartments in Toorak, by Roy Grounds (1940–41).

Image: John Gollings

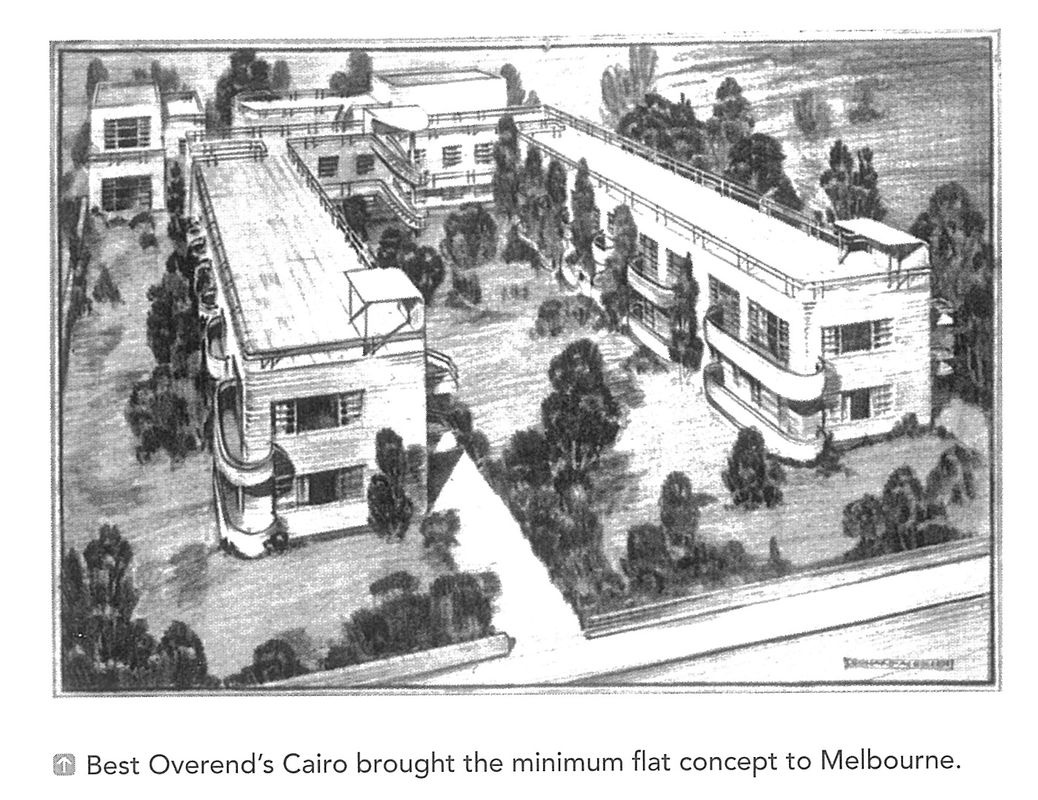

Architects of the era, whose grounding was in the design of single domestic housing, became involved with multi-residential projects with no less vigour. Projects such as Moonbria in Toorak (1940–41), Clendon in Armadale (1939–40) and Quamby in South Yarra (1941) by Roy Grounds as well as Newburn on Queens Road by Frederick Romberg (1939) and Woy Woy in Elwood by Mewton and Grounds (1935–36) were all distinctive examples of this architecture of the period. Many buildings included studio and small one-bedroom apartments with, in a number of cases, fold-down beds. Many of the studio apartments in Moonbria were thirty-seven square metres in floor area. It was Best Overend who led the way in this move towards compact living. His 1936 Cairo Apartments provided a fully functional home in just twenty-four square metres.

Circumstances changed in the post-World War II years, when the rising number of “six-pack” flats provided housing to the increasing population of migrants from Europe. Planning controls allowed three- and four-storey apartment buildings to be constructed throughout the inner and middle suburbs of Melbourne with little or no participation from architects. This coincided with an “uber modernist” moment: the construction of high-rise estates during the 60s as part of the Housing Commission of Victoria’s Slum Reclamation Program, a housing program for the poor involving the clearance of expanses of inner-Melbourne terrace housing. The scheme was abandoned in the early 70s in the face of community concern but today a significant stock of social housing from the period remains.

The Victorian Government responded to community disquiet in 1971 with an amendment to the Melbourne Planning Scheme (MPS) that effectively eliminated the delivery of multiple housing for the following twenty years. During these years, the primary growth in Melbourne’s housing supply took place in concentric rings around the fringe of the city – a significant policy-driven interference to the supply of housing. In contrast, by 2002 in New South Wales, architectural engagement was mandated to raise design standards in new multi-residential development through State Environment Planning Policy no. 65 (SEPP 65) – a form of which is being considered for implementation in Victoria in the near future.

Melbourne Terrace Apartments, Nonda Katsalidis (1994).

Image: John Gollings

In the early 90s, housing developments in inner-city Melbourne began to grow in number, particularly in former industrial areas such as Southbank. The architecture of these early buildings could be described as cut-and-paste faux-Georgian – an aesthetic beloved by real estate spruikers of the time. However, Nonda Katsalidis’s Melbourne Terrace Apartments (1994) and St Leonards Apartments (1996) led a substantial shift and paved the way for other architects with strong experience in single residential projects to be involved in multi-residential design. Projects including Kerstin Thompson Architects’ Fitzroy Townhouses (2001), Wood/Marsh Architecture’s Yve Apartments (2006), NMBW Architecture Studio’s Fitzroy Apartments (2003) and John Wardle Architects’ Dock 5 (2006) enhanced Melbourne’s standing as a design city.

Part of this growth in inner-city housing could also be attributed to the City of Melbourne’s Postcode 3000, a planning policy initiated in 1992 that actively encouraged residential development within the boundaries of the City of Melbourne. The scheme rapidly added to the supply of new housing in the city, particularly with conversions such as Hayball’s Riverside Apartments in Southbank (1994) and Fender Katsalidis’s Little Hero Apartments in the CBD (2010).

MY80, Hayball (due for completion in 2015).

Image: Courtesy of Hayball

Melbourne has now entered a new phase of residential architecture with the advent of a significant number of high-rise residential towers in the CBD and its fringe, initiated by developers from Singapore, Malaysia and China. These developers are funded by – and attract sales from – investors in their home countries, and their projects will extend the typology of Fender Katsalidis’s Eureka Tower. Projects such as Hayball’s MY80, currently under construction in Elizabeth Street in the CBD, is one example. This tower will consist of a range of apartment types including micro apartments and communal facilities such as sky gardens, a health spa, pool and gym plus communal living and dining spaces for residents – a vertical neighbourhood.

The extent of approvals granted for high-rise developments by the Minister of Planning – without recourse to third-party rights – has echoes of Melbourne’s dramatic gold-rush-driven and overseas investment boom of the 1880s, which created its now revered streetscapes of Victorian architecture. The swathe of developments also signifies Melbourne’s transition to a global city – and the impact on the city’s skyline, streetscape and culture will be dramatic. According to Grattan Institute research, “Australians do not all want to live in detached houses. Many want to live in a semi-detached home or an apartment in locations that are close to family or friends, or to shops … new supply is not reducing the [shortfall].”4

New planning settings will need to expand their scope well beyond character, plot ratio, envelope and mass. The manner in which land is assembled, provisions for amenity through intelligent design objectives and innovative construction techniques to offset shrinking dwelling sizes will be essential – and are all issues requiring a greater level of engagement with architects.

1. Professor Shane Murray, “Housing Architecture Research,” Architectural Review Australia,

No.086, 40–42.

2. National Housing Supply Council, “State of Supply Report 2008,” 17.

3. Mark Strizic, Robin Boyd: Living in Australia (Fishermans Bend: Thames and Hudson and the Robin Boyd Foundation, 2013), 64.

4. Jane-Frances Kelly, “Getting the housing we want,” Grattan Institute report, November 2011, 3.

Source

Discussion

Published online: 28 Jul 2014

Words:

Robert Stent

Images:

Courtesy of Hayball,

Courtesy of the Journal of the Royal Victorian Institute of Architects,

John Gollings,

Tom Ross

Issue

Architecture Australia, May 2014