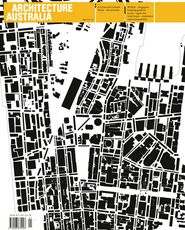

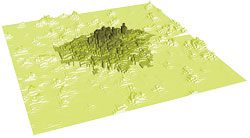

Shanghai density

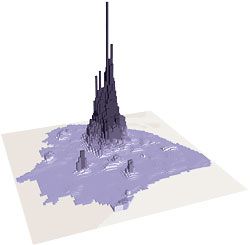

New York City density

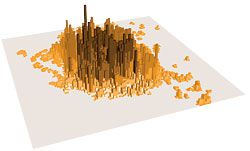

Mexico City density

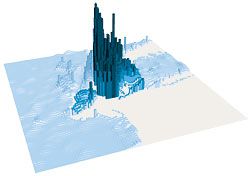

London density

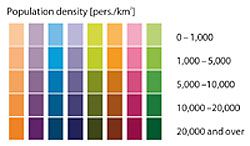

Diagrams showing relative city densities. Saskia Sassen argues that cities with multiple centres, such as London, may be better placed to cope with environmental pressures. Research and graphics courtesy of Urban Age, London School of Economics and Political Science, www.urban-age.net.

Global connections bring more than economic opportunity. Laura Harding comments on lessons learnt from the Metropolis conference held in Sydney last year.

The 9th World Metropolis Congress brought together mayors, officials, academics and industry representatives from the 104 cities that comprise the World Association of Major Metropolises. The congress was organized around a program of keynote speakers and workshops exploring four themes – city leadership, climate change, financing infrastructure and urban renewal. It was a strange experience for those used to the charisma-laden buzz of architectural conferences. This congress drew an extraordinarily eclectic range of participants. Presentations were spare, technically focused, highly compressed and workmanlike. Facts were presented honestly and without embellishment. Often the content was dry and intense concentration was required to stay focused. Yet over the four days, powerful comparisons with our national situation were drawn into sharp focus. In the reports from wealthy, urban megacities and the shantytowns of the developing world, we must take an equal serving of instruction and censure.

The congress wasn’t entirely a charisma-free zone. Nicky Gavron, the ex-Deputy Mayor of London, was energetic and engaging in her reflections on the London Plan. This plan has seen a city of 7.5 million people achieve the fastest shift in public transport usage of any major conurbation in the world. Londoners are cycling and catching the bus in unprecedented numbers in a country where Margaret Thatcher once famously declared, “If you’re seen on a bus after age 30, you are a loser in life.” Gavron outlined the targets that London is adopting for affordable, social and sub-market housing (we’d settle for a competent strategy for any of these, let alone all three), the success of the congestion tax (that our governments cravenly avoid) and recent proposals to improve the sustainability of new building projects and retrofits. Gavron noted that the climate change we are experiencing now is a direct result of carbon emissions from the 1950s, with the effects of five decades’ worth of emissions yet to come. She believes that the role of small cities in changing the world’s behaviour is critical.

While we fantasize about an ever-increasing global stature for Australia’s cities, we overlook the advantages of being small. Small cities and organizations are agile and can institute change quickly. In the Urban Mobility workshop we heard from Shan Ali of the Grameen Bank of Bangladesh. In 1976 this organization pioneered the idea of microcredit – the provision of small loans to the enslaved working poor and to beggars who have no capital with which to secure a loan from a corporate financial institution. Last year, the Grameen Bank loaned more than US$800 million to the world’s poor for micro-enterprise, housing and education and maintained a loan recovery rate of ninety-eight percent. Shan Ali was feverishly distributing photocopied notes from his backpack in an effort to spread the word.

Dr Rajendra Pachauri, Chair of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, was equally inspiring. While debate in Australia rages about the economic risks of setting tough carbon emissions targets, Dr Pachauri calmly reminded us that more than 1 billion of the world’s population don’t even have access to electric light.

Dr Saskia Sassen of Columbia University was touted as the spruiker of the global cities movement, yet proved to be critical and substantive. She challenged fundamental assumptions about global cities. Why is it that when digital technologies allow for population dispersal and increasing homogenization, the world’s cities continue to concentrate density and to trade on cultural specificity? Dr Sassen’s current research focuses on how density is constituted in urban form. Her analysis suggests that the multiple centrality of London’s or Mexico City’s urban form may have distinct advantages, in terms of its ability to cope with environmental pressures, over the more highly concentrated urban models of New York or Shanghai, which currently symbolize the urban metropolis.

Sydney’s contributions to the workshop sessions were often characterized by corporate marketing rather than open and genuine engagement with the issues. Sydney Water presented its 2015 targets, which boasted an aim for twelve percent of Sydney’s water supply to be derived from recycled sources, while skimming quickly through the fifteen percent target that will be drawn from the environmentally questionable desalination plant.

In the Waterfront Cities workshop, Richard Marshall from Woods Bagot told us that redevelopment “was not just for aggrandisement, but for the betterment of humanity”. Thereafter, the Sydney Harbour Foreshore Authority presented its waterfront renewal site at Barangaroo, where it is shoehorning additional floor space into a glorified business park and where, in an uncharacteristically blinkered interpretation of history, an ex-prime minister is setting about erasing the site’s industrial and archaeological heritage to re-create a 1788 headland over a multi-level car park.

Such bureaucratic chest beating sat awkwardly with Hannu Penttilä’s presentation of the more humble human aims of Helsinki’s waterfront renewal project in Ruoholahti. This was predicated on the extension of public transport, the provision of an equitable mix of housing and commerce and the reuse of existing industrial structures. Even more humbling were the projects described by Elisabete França, the Housing Secretary for Sao Paolo, which involved the relocation of shanty dwellers to create small public spaces that sought to reconnect the shanty towns to wealthy neighbourhoods, and the presentation by Professor Chetan Vaidya from the National Institute of Urban Affairs in Delhi of a community toilet program that provides clean water and hygiene education to the inhabitants of the Sangli Wadi slums.

There were some admirable local contributions. Clover Moore, representing the City of Sydney, was impressive on the practical initiatives of the City’s 2030 Strategy, as was transport planner Christopher Stapleton, who delivered a bravura critique of Sydney’s public transport system. The Redfern Waterloo Authority concentrated its presentation on its construction training programs for local unemployed people. Members of the public attended a series of free lectures and an accompanying series of Connecting Cities Research Papers, prepared by the Congress organizers, offered an excellent background to the conference themes. It is impossible to capture the breadth of issues explored at the congress.

Many delegates were disappointed by its awkwardly bureaucratic tone, but for me it made an essential point very powerfully. Our global connectedness is not simply an opportunity for economic expansion and predation. We should be utterly ashamed of our apathy and hand wringing over the challenges that climate change and urban renewal present to us. Our tasks are modest compared to those faced by other world cities. We must use our connectedness to form a far more balanced sense of the challenges we face, keep the economic naysayers at bay and, to quote Dr Pachauri, “be the change we want to see in the world.”

Laura Harding is a Sydney-based practitioner. In the interests of disclosure, she notes that she was part of the team that won the International Design Competition for the Barangaroo Waterfront.