GEVORK HARTOONIAN REVIEWS THE EXHIBITED PLANS TO REBUILD NEW YORK’S GROUND ZERO.

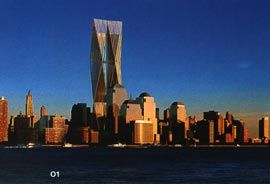

Battery Park view of the elegant twin-looking towers proposal by Fosters and Partners.

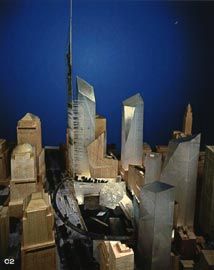

Proposal by Studio Daniel Libeskind.

Proposal by Peterson/ Littenberg Architecture and Urban Design.

Skyline view of the proposal by Richard Meier & Partners Architects, Eisenman Architects, Gwathmey Siegal & Associates and Steven Holl Architects.

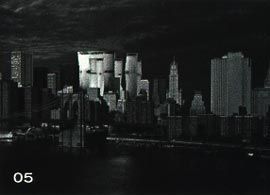

Brooklyn Bridge view of the proposal by SOM, SANAA, Michael Maltzan Architecture, Field Operations, Tom Leader Studio, Inigo Manglano-Ovalle, Rita McBride, Jessica Stockholder and Elyn Zimmerman.

The towers of culture proposal by Think Design: Shigeru Ban, Frederic Schwartz, Ken Smith, Rafael Vinoly, with contributors William Morrish, David Rockwell, Janet Marie Smith and engineers Arup, Buro Happold and Jorge Schlaich.

Worms eye view of the proposal by United Architects.

IT IS CHALLENGING to think of civic architecture in New York City. The task is particularly daunting when the site is afflicted by the September 11, 2001 terrorist attack. As delirious it looks, Manhattan’s tight grid and block system resists projects that do not comply with the city’s structural logic. This poses a serious challenge to architects, urban designers, and planners who, for the last three decades, have been trying to formulate a different relationship between architecture and the city. Recently, the debate on architecture and the city has taken a new direction, with some considering infrastructure to be a critical force in transforming contemporary metropolitan cities. Ironically, New York mayor M. Bloomberg and a few architects believe that infrastructure – a hub of local and regional metro system – is an appropriate solution for the ground zero site, at least for the time being. In this context, a major problem with the seven projects proposed for the reconstruction of the World Trade Centre – on display in the Winter Garden of Battery Park City – is that none of them are primarily informed by the idea of infrastructure. Most projects, indeed, re-interpret what is already there – density, high-rise buildings and green surfaces.

The brief to which these proposals responded is complex and unclear: the design should provide a memorial site (to be developed through another international competition); it should consider entrances and space for the local subway station and the Path trains to New Jersey; and should propose office buildings for commercial and public use. There are many ideas about how to choose and why to choose a particular project. Some are of the opinion that the winning project should include bits and pieces from each entry! Luckily, this idea has been shelved, at least for the time being.

In addition to the exhibition, visited by hundreds of people daily, there have been, in the last month alone, community talks, presentations by the architects involved, and public polls. An unofficial result of these public hearings was announced on 17 January: The New York Times disclosed three projects, those by Foster & Partners, Peterson/ Littenberg Architecture and Urban Design, and Studio Daniel Libeskind, as the most wanted by the public. The threads linking these proposals include attempts to highlight the footsteps of the destroyed towers; to orient the complex towards the West End highway; and to outline a conceptual statement, associating remembrance of the past with the hope of a new future.

Foster has proposed an elegant and intelligent twin-looking tower whose 1765 foot height will dominate the skyline of Manhattan. The proposal comprises three elements – a tower, a void, and a park surrounding these. Located on the eastern end of the site, and looking towards the west end highway and the Hudson River beyond, the tower offers a new beacon to the city. The Peterson/Littenberg proposal, on the other hand, recalls old solutions for new problems. Its overall composition and the chosen architectural language offer nothing beyond urban ideas developed in the last hundred years. A pair of tall building dominates a huge enclosed park that is surrounded by another three short office buildings. The typological convention of public arena as a closed space is further stressed by the setbacks of the towers.

Libeskind’s project has received a good deal of attention for many reasons, including the fact that he has designed many memorial buildings around the world and the use of a compositional language that is appealing to a public who gets excited with anything resembling the rhythm and the visual effects of Hollywood blockbuster movies. The project embodies interesting ideas: the memorial area, located 70 feet below the ground and next to the concrete retaining wall that survived the attack, is conceptually exonerated by both a museum which dominates the open public space, and a tower to its north. The idea of hope is also implied in the tower’s spire, with its figural gesture which parallels the arm of the Statue of Liberty. The street-level public space is open and yet surrounded by four additional office buildings running along Church Street, and a semi-circular lifted promenade. The two themes employed by Libeskind, the idea of open/closed public space, and the placement of green areas at different levels of the complex re-occur in every other proposal.

The project proposed by a team of designers called “Think” has received the least attention. The design, by internationally known architects Shigeru Ban and Rafael Vinoly, among others, suggest three different schemes called “Great Hall”, “Sky Park,” and the “World Cultural Centre.” Although the two towers of the latter scheme are located above the footprint of the destroyed twin towers, its structure only touches the periphery of the site. The elegant towers are made of a lattice structure, the void of which is occupied by volumes placed at different levels. The design recalls Tatlin’s famous tower but, devoid of any political message, it indeed looks melancholic.

The remaining three proposals interpret the idea of the tall building and its relation to the city differently. The idea of hope is radically expressed in a scheme proposed by The United Architects – Greg Lynn, Reiser + Umemoto, and K. Kenon. An L-shaped wall of five towers, different in height and form, surround the area dedicated to the memorial building. A wormeye view of these towers recalls the phenomenological healing sought in the circular dance, if not La Danse, a Henry Matisse painting.

Manhattan’s uniqueness lies in its density. The project by SOM, Sejima and Nishizawa and others, exaggerates the idea in a cluster of worm-like towers, organized around a nine-square plan, that twist, roll, and fall over each other. The forest-like composition presents a futuristic image of the Manhattan to come. The suggested density and the playful verticality of the design is balanced by what they call a “Trans-horizon” – an image of the global city that integrates horizontality with verticality, but also replicates the green areas of the ground floor at different levels. The idea of balancing the vertical with horizontal is also the starting point for a design proposed by Peter Eisenman, Richard Meier, Steven Holl and Gwathmey Siegel.

The diagram of the scheme is a blasted vertical volume, the drawing of which recalls the late John Hejduk’s work, that transgresses the archetype of “wall” and “column.” The design juxtaposes two disjointed and perforated “walls” whose wallness is deconstructed by five vertical volumes soaring up as high as 1111.00 feet. These architects offer the most conceptual scheme, but it has the least chance of being built. Although the perforated walllooking structure fits pretty well within the surrounding buildings, at least at street level, its overall composition resembles an object fallen from another planet. Nevertheless, the design vigorously integrates the volume with the grid of Manhattan. Like the five fingers of a hand, the project extends beyond the nominated site, reaching out and providing several unique public spaces, including a memorial site floating in the Hudson River.

Although none of these proposals might be constructed, the entire effort is promising. One could outline the weak points of each proposal, but any judgment should consider the fact that Manhattan’s morphological structure has been exclusive since its inception; the grid, the block, with a large green carpets at its heart (Central Park) leave no room for the civic or public spaces known in traditional European cities. In the absence of a philanthropic vision, which sees the city as a public work, the realization of anything similar to the Rockfeller Centre at ground zero seems an unattainable dream. Marked by the remembrance of 9-11- 01, the site of ground zero will remain attractive no matter what is built. The conflict between people’s morality, the prevailing culture of tourism, and the economic logic of gridiron city (to replace every fallen building immediately by a new one) points to the changing perception of architecture’s public function in this city. It also reiterates the conventional essentiality of the idea of event, even a tragic one, for the realization of civic architecture.

GEVORK HARTOONIAN, NEW YORK CITY, JANUARY 2003.