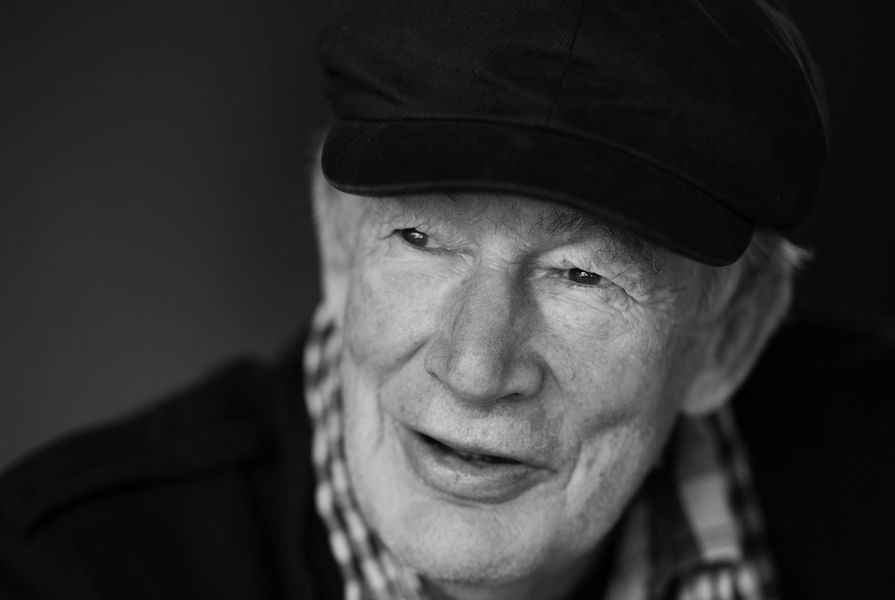

The passing of Ian Athfield (1940-2015) on 16 January 2015 marks the end of an era in New Zealand architecture, which, owing largely to the magnanimous presence of Athfield and his architectural work, is tinted with a persistent pursuit of idealism rarely seen elsewhere since the middle of twentieth century. Lovingly known as Ath by those around him, he will be remembered, first and foremost, as a man of extraordinary humanity.

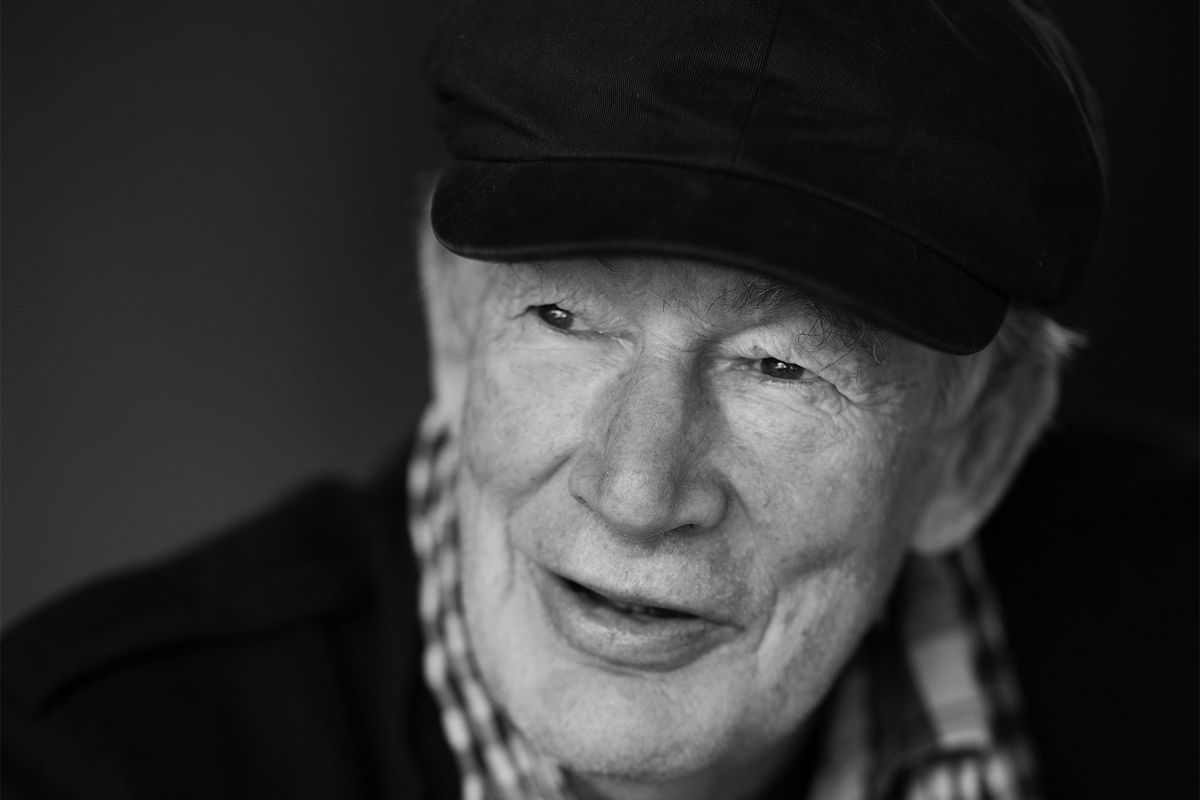

Athfield’s life was defined by the high visibility of his architectural forms and his colourful personality. A small church building – the First Church of Christ Scientist (1980) – looks like a strange marine creature that has stumbled into Wellington’s charming Willis Street. Is it an exotic serpent, or a turtle, with its large, single stained-glass eye winking at the dental clinic next to it? The Athfield house and office is Athfield-idiom par excellence: a white-plastered Greek village, somehow remoulded by the hands of a wayward alien, spattered boundlessly on the hillside of Wellington’s genteel suburb of Khandallah, like an uncontrollable exotic plant growing aggressively among its indigenous neighbours. Indeed, the Athfield house is neither a New Zealand farm house influenced by the country’s colonial heritage, nor an indigenous Maori meeting hall. A neighbour, terribly repulsed by the look of these buildings, decided to show his displeasure by shooting a few bullet holes in them. But ever since Athfield started building his house and office in 1965, this white-plastered village has won much affection and numerous architectural laurels. It has become an inseparable part of Wellington’s breath-taking landscape of hills and harbour.

When the USS nuclear warship Truxtun sailed into Wellington harbour in 1976, the Kiwis marked a proud historical moment by decking the bullet-like tower in the Athfield house with a boldly lettered slogan: “Keep New Zealand Nuclear Free.” The interior of this imposing tower is accessed by an impossibly narrow spiral staircase, or from the roof terrace. For a long time it contained only a single drawing board. Illuminated by an oculus and two bubble-like skylights, with two round nautical windows protruding out towards the harbour and horizon, this was a room of solitude.

The Athfield house and studio on the hills above Wellington Harbour.

Image: Xing Ruan

But Athfield was known for his gregariousness. In our carefree days in Wellington in the early 1990s, my partner Dongmin worked for Ath, while I combined teaching and doing a PhD on the village lives and structures in southern China. We looked up to Ath, a towering figure, for some career advice in architecture. To our surprise, he gave us only this: “You have time on your hands, go and make beautiful babies.” In hindsight, if we had listened to Ath, our children would have benefited from the village life in the Athfield house. There were twenty or so people working in the office, which was part of the village; and there were tenants of common and uncommon character. The Athfield seniors lived in the upper house, who prepared snacks for morning and afternoon teas; the sublimely beautiful and talented Clare ran the interior work, and the Athfield juniors were around. The peacock had mysteriously left, so I was told, but the parrot was still there, mocking only the annoying clients. There was also goat, the “Flying Mower”; in his grand old age he moved about the village gracefully, completely indifferent to the the property’s dogs.

Inside the beautiful, odd and confronting forms of the Athfield house and office lies an ideal: that architecture should be a village. A village, according to Ath, is one of the most important building blocks for a society, because it is big enough to withstand the pressures of family, but it is small enough to form a face-to-face community. Like a vast Renaissance villa, the Athfield house in plan is a loose ensemble of small and large rooms of different characters, more interconnected than segregated. In 1976, the International Design Competition for the Urban Environment of Developing Countries, focusing on Manila in the Philippines, was initiated and run by the International Architectural Foundation and some of the world’s leading architectural journals. Among the 476 entries from 68 countries, Ath’s self-help housing village scheme won the first prize, which was judged by Balkrishna Doshi and Moshe Safdie. The winning parti, needless to say, comes from the Athfield house and its village ideal.

Ath was ahead of his time and designed what we now label as sustainable architecture for low-carbon living. Like his other buildings, the Philippines housing scheme is unbashful: it screams for visibility with featured water cooling towers, ventilation pipes, windmills, water heating tanks and solar panels. But the competition scheme was also a comprehensive package of self-help building instructions, including thorough considerations of the community, water recycling, cooperation, industry, ownership, building materials (local coconut palm tree was proposed as the principal building material), individual units, energy centres, services and conservation, finance, community centres, transport and vehicles.

After winning the competition, Ath was invited by the 1976 Habitat in Vancouver, the first United Nations Conference on Human Settlements, to build a demonstration self-help house from his competition scheme. The conference, however, was overshadowed by the politically motivated protests against the competition by the Tondo foreshore squatters in the Philippines, the people whom the competition was specifically designed to help. The protest was triggered by the fact that none of the squatters had been consulted about the resettlement plan, which, ironically, was supposed to be the driving force of Ath’s scheme. Ath also had to endure an ill-conceived stage conversation with the famed anthropologist Margaret Mead. He soon realised that his mischievous sense of humour could not possibly be effective in dealing with the entangled politics at the conference. Ath then quietly went about his business of putting together an on-the-spot illustration of his minimal Tondo house, made from old plywood, logs, salvaged timber and plaster covered mesh.The Philippines housing competition winning entry was never realised. Ath, as he wryly laughed it off years later, did not know that the money for his Philippines housing project was used by Mrs Marcos to buy her shoes.

Ath was a builder, and he often ridiculed himself as a poor one. But he continued to build here and there, mainly on his own house. I once asked Ath why, despite different structural systems, he always preferred to cover his buildings from roof to wall, inside to out, in white plaster. He replied: “I want to cover the sins of construction!” There is no shipshape perfection or impeccable detailing in the Athfield house. Instead it is full of trial and error, and above all, human warmth. Are the splendour and efficacy of his architecture any way diminished because of its imperfect execution? Of course not. Ath inherently knew that the deliverance of architecture as a social art should not succumb to the way in which it is fabricated – a common misconception held dear by many in modern times. As a result, Ath was immune to a fatal trap present in all arts – that is, the pursuit of deadly perfection.

The Athfield house and studio’s signature white plaster covers walls both inside and out.

Image: Xing Ruan

Ath relentlessly delighted in his own sometimes socially confronting humour. When Dongmin began working for Ath, she had limited command of English. That she had trouble in putting her tongue in between her teeth when pronouncing “Ath” gave endless good laughter to the office. Yet Ath arranged to have Dongmin sitting next to the phone so that she must answer incoming calls from clients; he anticipated with a great deal of joy the slight confusion and panic among his clients caused by this young Chinese architect. People were completely given to Ath’s eccentricity, and Dongmin in this light-hearted environment gained her confidence in speaking English.

In 2009, Dongmin and I took Shumi and Shuyi, who were not born early enough to have been part of the Athfield village, to visit Ath, Clare and the office. Shuyi slept in the tower, and Shumi had a cave-like room. The maze-like village, of course, enthralled them, but they were a little disappointed – a character or two still appeared here and there, but they were not surrounded by droves of people young and old, as promised by their parents. Ath ploughed on, telling me about his plans to make tweaks to the village. I enquired about the heritage status of the building. Ath gave me his sly grin: “It has been classified as ‘postmodern organic’, so I can do whatever I like!” But Ath at this very moment struck me as a lonely warrior.

Now Ath has left us. I know, though, that his magnanimous legacy demands that we engage with architecture as a social art, and he will be content in the heavens knowing that the battle will continue.

Source

People

Published online: 12 Feb 2015

Words:

Xing Ruan

Images:

Xing Ruan

Issue

Architecture Australia, May 2015