The RVIA Small Homes Service (SHS), established in 1947 with Robin Boyd as its first director, sought to popularize the modern home and make it available to a broad public. Catering to the rapidly expanding suburbs of the postwar boom, a time when building materials were scarce and the size of homes was prescribed, the SHS showed how good design could creatively overcome these constraints.

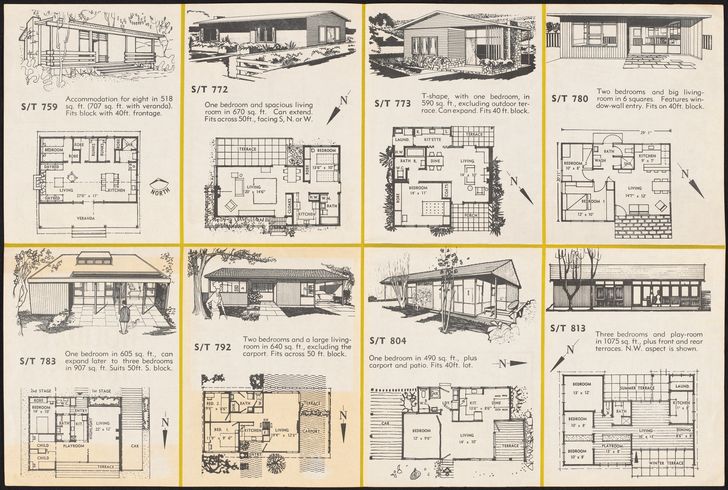

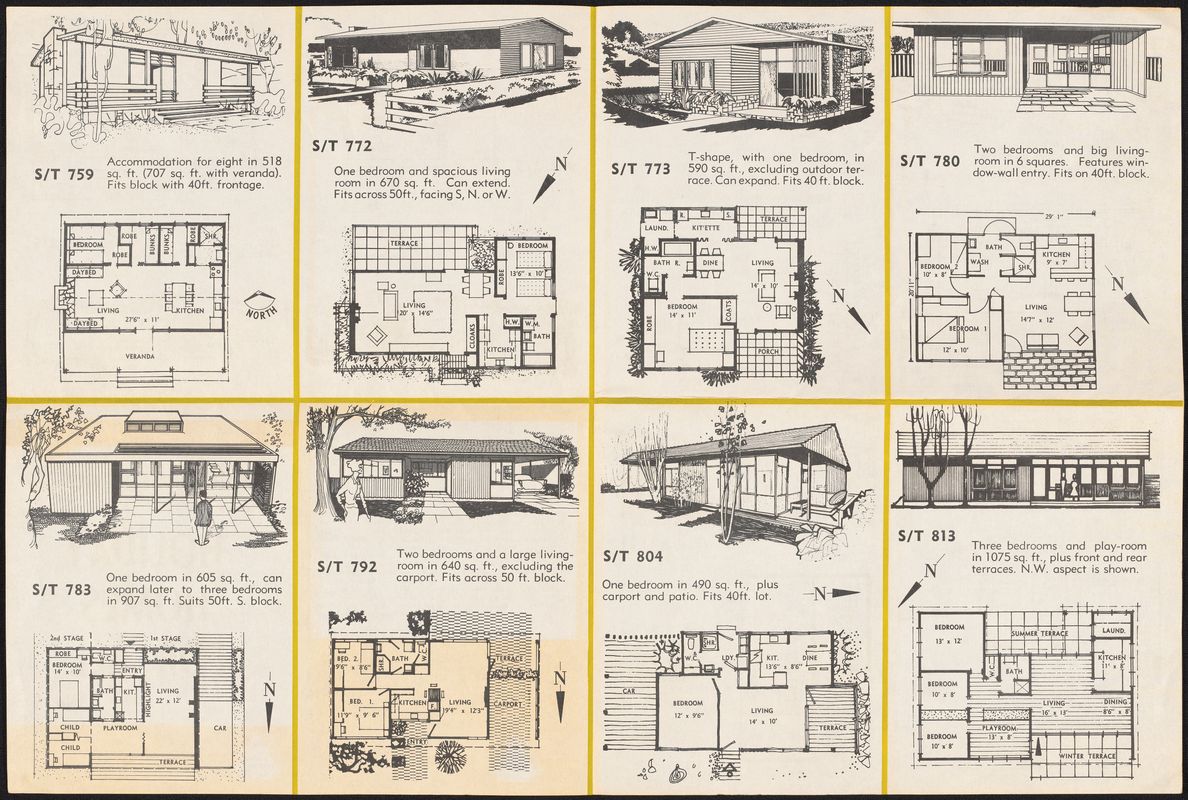

Boyd set up the SHS within the building of the State Electricity Commission of Victoria at 238 Flinders Street, Melbourne, where he managed a small team of architects and draftspeople. Each week, they would produce a design for a modern home, which would be published in The Age newspaper alongside a column by Boyd advocating for modern design and the new ways of living it enabled. The designs were characterized by an economic use of space, good solar orientation and maximized living space, and made use of the whole suburban block as a total environment. Small details, such as having separate rooms for the shower and toilet, allowed the bathroom to become more flexible. In essence, it was about “doing a lot better with less.”1 Plans and specifications of these houses could be bought direct from the service for the modest fee of five pounds, ready to be built by a local builder on a plot in the new subdivisions. It had an immense positive impact, with some 5,000 homes built directly from SHS plans, an estimated 15 percent of homes in Victoria at the time,2 and placed the idea of good design in the public consciousness.

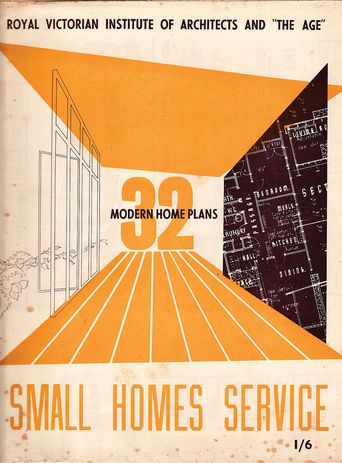

Folded booklet of house plans prepared by the Small Homes Service New South Wales, conducted by the Royal Australian Institute of Architects (New South Wales chapter) in conjunction with Australian Home Beautiful at David Jones, Sydney.

Image: Courtesy National Library of Australia

But toward the end of his life Boyd could already see the deleterious effect suburban sprawl was having on the physical and social fabric of the city. He turned away from the freestanding private villa and instead advocated for new medium-density typologies. Writing in 1971, only months before his untimely death aged fifty-two, he asked, “Is it just that the Australian public clings to its depressing little boxes because it knows no better, has seen no better design?”3 Boyd’s warnings went unheeded and the suburbs continue to extend further towards the horizon today. Meanwhile, the practice of architecture has all but abandoned the suburbs, instead hitching its wagon to the boutique luxury apartment market of the inner ring. Could these issues be addressed with a new Small Homes Service for today? What would such a program look like? And if he were here now, what would Boyd do?

Initially a collaborative endeavour between The Age newspaper and the Royal Victorian Institute of Architects, the Small Homes Service sought to make well-designed modern homes accessible to a broader public.

Image: Courtesy Robin Boyd Foundation

I believe he would start by first defining the problem. Because while the challenge to provide adequate and suitable housing for all remains the same, the particular pressures of today have led this challenge to take a unique form. There are more of us than ever and yet fewer people are living together. Young people can’t get on the property ladder, while empty-nesters aren’t downsizing. The city continues to expand, yet most of the new jobs are in the centre. More women are in the workforce, but men aren’t leaving it, or making up the difference at home. Traffic is getting worse, yet we build more roads, not rails. The ageing population needs to be cared for, while public services are under pressure. Essentially, the temporal, social and economic structure of work and family life is being stretched to breaking point, an issue compounded by the increasingly diffuse spatial structure of the city. Or put another way, we want the suburbs, but the suburbs aren’t looking after us. They are a twentieth-century typology that no longer fits twenty-first-century life.

And yet the suburbs are what we’ve got. Australia is overwhelmingly a suburban nation, with an estimated 86 percent of people living in suburban areas.4 These areas are dependent on cars, poorly served by public infrastructure and services and plagued by traffic. But rather than decrying the suburbs as unsustainable burdens that will drag us all under,5 the challenge for the coming decades will be to retrofit these suburbs to become socially, environmentally and economically supportive places in their own right.

A new Small Homes Service would not be designing new homes to address this challenge. It would be geared toward adapting the existing housing stock to suit the needs of today and creating new opportunities to share space and resources – a Small Homes Adaptability Service. The suburbs are ripe for this kind of transformation. They are composed of many freehold titles, enabling owners to proceed independently rather than waiting for any top-down coordination. They have plenty of underused space: front yards, backyards, broad streets, verges, crossovers, garages and spare rooms. And perhaps most importantly, they have always been about freedom to experiment, to be transformed from the bottom up in incremental ways.

A speculative project by Other Architects, the Offset House proposes to densify existing suburban houses by subdividing them internally, and turning private backyards into a shared space.

Image: Tobias Titz

The kinds of transformation this Small Homes Adaptability Service would initiate would focus on energy, production, caring, creativity, sharing and conviviality. It would endeavour to create places that are self-supporting and productive, rather than merely places to sleep between commutes. It would adapt and join adjacent triple garages into co-working spaces and workshops, shared by the entire block, to support decentralized working. It would install solar panels and link up existing ones to create local energy smart grids, for charging cars and reducing bills. It would adapt front rooms for childcare and social clubs for the elderly, providing space and structure for the informal systems of care that already operate. It would redesign existing dwellings to accommodate different family types and uses, such as adding a separate entrance and kitchenette to a larger home to allow a student to cohabit with an elderly owner in relative peace, or adding a level to accommodate a growing family. Lightweight digital services could be introduced to facilitate sharing of tools, cars, books and time among neighbours. The simplest intervention might be to knock down a fence between dwellings, creating a new semipublic realm of shared facilities, from swimming pools to basketball hoops.

How might the logic of the original SHS be applied to achieve this? Boyd would have used his considerable profile to initiate a broad public conversation on the state of our homes and our lives. (Although, with The Age no longer the platform it once was, he would more likely be hosting The Block.) With this positive cultural program underway, he would have made the tools for this transformation easily available and affordable. Today that would mean embracing the open-source movement to put power into the hands of individuals, changing the city through their accumulated efforts. Finally, he would have set an example himself by moving to the suburbs and building a demonstration project for his own family. Today this role could be taken up by local government in partnership with the universities, offering a 1:1 vision that’s easily communicable, exciting and beautiful.

This all sounds straightforward enough, but it amounts to a complete recasting of the role of the architect today. If a typical residential architect does ten projects a year, what would a practice look like that could do ten projects a day? To use medicine as an analogy, the Small Homes Adaptability Service would recast the architect as a family GP, providing minimal service over a long period of time, writing prescriptions and providing advice, connected to a neighbourhood and the people in it. In this way architects could reclaim public trust by demonstrating our responsibility to the city rather than to our portfolios.

What kind of city does this set of prescriptions add up to? I imagine it to be more like Tokyo than Templestowe. High-density, low-rise, multifunctional, green, vibrant and well connected. With Melbourne’s population expected to double by 2031 and the population of Victoria to hit ten million by the 2050s,6 we could do worse than aim for this most charming of megacities. The Small Homes Adaptability Service would work to accommodate this growth within the existing urban boundary, densifying places to live and decentralizing places to work, improving the quality of life for all Melburnians. I’m sure Boyd would approve.

1. Philip Goad, presentation at “What Would Boyd Do? Small Homes Service for Today” event, chaired by Rory Hyde, MPavilion, 15 October 2017.

2. Geoffrey Serle, Robin Boyd: A Life (Carlton: Melbourne University Press, 1991), 92.

3. Robin Boyd in Ian McKay, Robin Boyd et al. (eds), Living and Partly Living: Housing in Australia (Thomas Nelson, 1971), 8.

4. David Gordon, “Is Australia a Suburban Nation?” Alexandrine Press, 30 June 2016, alexandrinepress.co.uk/ blogged-environment/australia-suburban-nation.

5. A typical example of the “evil suburbs” genre: Royce Millar and Ben Schneiders, “Are Melbourne’s sprawling outer suburbs destined to become ghettos?” The Age , 2 July 2017.

6. Stephanie Anderson, “Melbourne’s population tipped to double as Victoria grows to 10 million, new projections show,” 15 July 2016, abc.net.au/news/2016-07-15/melbourne-double-in-size-as-victorias-population-10million/7632700.

Source

Discussion

Published online: 19 Jun 2018

Words:

Rory Hyde

Images:

Courtesy National Library of Australia,

Courtesy Robin Boyd Foundation,

Edmund Sumner/VIEW,

Robert Frith,

Rory Hyde,

Tobias Titz

Issue

Architecture Australia, May 2018