Sydney’s new commercial tower, 8 Chifley Square by Lippmann Partnership and Rogers Stirk Harbour and Partners (RSHP) for Mirvac, deftly interprets commercial requirements and City of Sydney planning regulations to create a tower of significant presence. Following a successful collaboration on the runner-up scheme in the East Darling Harbour (Barangaroo) Masterplan Competition, Lippmann Partnership invited RSHP to join them for 8 Chifley Square. The concept design was begun in Australia and many of the building’s defining concepts, including the roof terraces and vertical villages, were explored prior to an intensive design collaboration between the two firms in the London office of RSHP. Design authorship and accreditation are equally shared.

Located between Elizabeth and Phillip Streets and fronting the semicircular Chifley Square, the site occupies a distinct node in the urban fabric of Sydney. The new building needed to assert its identity, being adjacent to the 126 Phillip Street (Deutsche Bank) building by Foster and Partners with Hassell, and the postmodern Chifley Tower, designed in the 1980s by Kohn Pedersen Fox and Travis Partners. However, 8 Chifley Square was potentially going to be a comparatively diminutive tower due to a combination of the Martin Place shadow plane restricting its height to the height of Deutsche Bank and the site’s small area requiring an envelope that would cover the full site to create a commercially viable floor plate. The latter requirement meant that the building could be limited to approximately fourteen storeys, which would have severely reduced its presence.

At street level, a six-storey-high atrium extends the public space of Chifley Square. A glass lobby is hung from the soffit on stainless steel wires.

Image: Brett Boardman

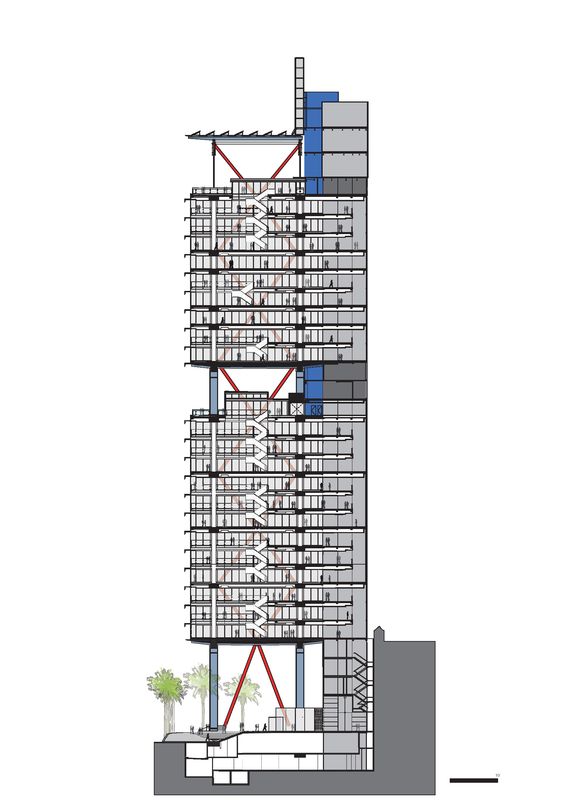

To provide street-level presence and increase the building’s height, the office floors of 8 Chifley Square have been raised six storeys, creating a publicly accessible ground plane that extends Chifley Square. The scale of this space acknowledges the street wall height of the surrounding context in the form of a “reverse” podium, dramatically animated by an RSHP signature, expressed red steel bracing. The tower is articulated with an exuberant exposed structure and finely detailed materials. Giant angled blue steel columns transfer internal tower columns to the base of the building’s perimeter “mega” columns, creating a column-free ground plane, while precast concrete panels with an exposed steel primary structure create a finely detailed and elegant structural expression on the soffit of the public space. Within this space a frameless glass lobby is literally hung from the soffit on stainless steel wires. A second, smaller structure – a circular steel and glass cafe – is somewhat less refined. A diagonal stair directs the visitor from the street intersection to the building entry.

The public expression of open space at the building’s base is reiterated at its midpoint and roof level with a sequence of accessible terraces. These terrace spaces further increase the vertical scale of the building, while creating a sense of public-ness seldom found in commercial buildings. In Sydney’s benign climate, they create the opportunity to integrate an outdoor lifestyle into work and the city.

The tower features three- and four-storey villages linked by a central void and stair. A terrace on the eighteenth floor offers rare public space within the tower.

Image: Brett Boardman

Due to the site’s small area, a full-site floor plate achieves approximately 1,000 square metres of net lettable area, which, while reasonable, is at the bottom end of the spectrum for commercial floor plate sizes and a far cry from the market preference of 1,500–2,000-square-metre floor plates. Recognizing this, Lippmann Partnership and RSHP created a series of three- and four-storey villages by vertically linking floor plates together through a void and interconnecting stair. This created vertical villages of 2,250–3,000 square metres, meeting the market perception of ideal office areas, and in the process redistributing the floor space ratio vertically to further extend the height of the building as well as capturing views of the harbour.

With three street frontages and an adjoining building on the south side, this design was always going to be a side core typology. In this case the reinforced concrete core is clad in a pressed metal panel, giving it a lightness and semi-industrial quality consistent with the work of both architecture practices. Glazed lifts are expressed externally, animating the core to the street, while external stairs hang lightly off the core, recalling those on Rogers’s Lloyd’s of London building while conveniently avoiding the City of Sydney’s floor space area calculation. The stairs’ fine yellow steel structure provides a delicate tracery that is a welcome surprise in the Sydney streetscape.

The commercial tower features four “mega” columns and red steel bracing – a RSHP signature.

Image: Brett Boardman

The external expression is dominated by four concrete “mega” columns with bold red cross bracing in between. The fine exterior finish of the concrete columns is achieved through the use of precast “sleeves,” which act as permanent formwork. The mega columns and their bracing are outside the building’s glass skin, creating a commercially desirable column-free perimeter. Horizontal external sunshades, which double as a cleaning gantry – eliminating the need for a building maintenance unit – align with these mega columns to define a second perimeter zone that shades the floor-to-ceiling glazing. The sunshades also fold down to provide protection from low-angle sun on the east and west facades, contributing to the building’s 6 Star Green Star Rating from the Green Building Council of Australia.

The relationship between Lippmann Partnership and RSHP goes back twenty years and this project’s success is in large part a result of their close collaboration. The two firms were aligned in their commitment to realize a tower that responds to Sydney’s climate and urban context and to the Australian work culture. They understood the commercial reality of this type of building while proposing a vision of what such buildings may look like in the future.

Though having all the hallmarks of the completed scheme, the initial competition design was, when compared with typical City of Sydney design excellence competition submissions, quite conceptual. This may reflect the more considered pace of design in the United Kingdom, or the difficulty for collaborating firms in agreeing on a final design. Whatever the reason, the design team has achieved a polished result through commitment and integrity. The 8 Chifley Square building is the first premium-grade high-rise to emerge from Lippmann Partnership and while displaying a design approach, materiality and social agenda consistent with previous projects, it represents a bold step forward in the scale of the studio’s work. As it is the first building completed in Australia by RSHP, the practice that has designed the International Towers Sydney at Barangaroo (due for completion mid-2015), we should look to see what it says about its work in Australia and how it compares to its European portfolio. The design of 8 Chifley Square incorporates the principles of the RSHP practice: public domain, legibility, flexibility and energy minimization. A generous public domain that extends the adjoining square is created at the ground plane. The building’s separation of servant and served spaces in its expressed core and structural expression provides clear legibility. The perimeter core and exterior structure create flexibility, while the shading contributes to energy minimization. These principles were evident in the iconic Lloyd’s of London building and this lineage clearly defines 8 Chifley Square as belonging to the RSHP portfolio.

Yet while this is a good building, there are lingering questions. Is it one of their best and what does it say about the current direction of the practice? A comparison to RSHP’s Leadenhall building in the City of London – which opened in late 2014 – is instructive. Leadenhall shares many of the same principles: a large public undercroft that creates a new public domain, a side core and external mega frame for flexibility, visible structure and core for legibility, and a double-skin facade encapsulating the mega frame for energy minimization. However, Leadenhall integrates these into a cohesive whole that in its sophistication and more restrained expression possibly points the way forward for the firm’s evolution, while 8 Chifley Square, to this author at least, references the detailing and expression of RSHP’s past projects.

While comparisons to Lloyd’s of London and Leadenhall may be made, 8 Chifley Square is a tribute to both firms and an all the more remarkable achievement for being realized under the cost-conscious climate of Australian clients and builders. The appearance of Richard Rogers and Ivan Harbour at the building’s opening ceremony is testament to the collaboration between client and architects and their shared vision of the design. The RSHP partners are, in fact, only the second group of international architects to attend the opening of their building in Sydney. Lippmann Partnership and RSHP have made a remarkable new addition to the skyline of Sydney. We eagerly wait to see whether the commercial towers at Barangaroo by RSHP and Lend Lease will achieve a similar quality to that reached at 8 Chifley Square.

Credits

- Project

- 8 Chifley Square

- Architect

- Lippmann Partnership

NSW, Australia

- Project Team

- Tim O’Sullivan (project architect); Ed Lippmann, Ivan Harbour, Andrew Partridge, Kate Humphries (design architects)

- Architect

- Rogers Stirk Harbour & Partners

United Kingdom

- Consultants

-

Access consultant

Morris Goding Access Consulting

Artist Jenny Holzer

BCA consultant Philip Chun & Associates

Builder Mirvac

Civil and structural consultant Arup

Construction manager Domenic Callinan

Developer Mirvac

Electrical and mechanical consultant Arup

Environmental consultant Arup

Geotechnical engineer Douglas Partners

Hydraulic consultant Arup

Lighting consultant Arup

Project manager Simon Healy

Public art consultants Barbara Flynn

- Site Details

-

Location

Sydney,

NSW,

Australia

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Category Commercial

Type Tall buildings

Source

Project

Published online: 1 Apr 2015

Words:

Philip Vivian

Images:

Brett Boardman

Issue

Architecture Australia, January 2015