The Andrew N. Liveris Building at the University of Queensland’s St Lucia campus is a bold work of architecture. But is it too bold?

Some would say yes. Equally, some would dismiss this project – a joint effort between Lyons and M3 Architecture – as a colourful, seemingly hermetic and anti-contextual building dropped in from outer space (or Melbourne) and wrought with a sensibility that tracks architectural lineages at odds with a Queensland vernacular. If this is your first take, then I would encourage you to park that assessment while you undertake a closer reading.

I use “reading” with intention, as the Liveris building is generated by narrative, anecdote and a rich array of overlapping ideas. The practice directors driving the design team, Carey Lyon of Lyons and Michael Banney of M3 Architecture, undertook – almost concurrently – the practice- based PhD model at RMIT University’s School of Architecture and Urban Design, graduating with doctorates in 2018 and 2017. The development of their dissertations enabled both authors to articulate a very clear approach to their design and conceptualization process. For Banney, archi-tectural ideas are born of specific observations, anecdotes and stories – often, of things overlooked or uncovered through careful investigation. For Lyon, it is a process of generating a complex web of myriad ideas, events, histories, patterns and details, then distilling these into a rich yet clear synthesis. In collaboration, these two architectural minds initiate a commitment to the importance of ideas to drive an outcome that can be supported through spatial expertise and technical resolution.

The joyful and engaging interior gravitates around the Pilot Hall, a large, multistorey subgrade testing facility.

Image: Christopher Frederick Jones

The winner of an international design competition, the scheme stood out from a field that included Conrad Gargett and OMA, Grimshaw, Woods Bagot and John Wardle Architects, among others. The authors of the Liveris building noted that their collaboration was 100 percent balanced in terms of conceptual contribution and was sustained by a constant dialogue, friendship and the ability to “trust each other’s eyes.” Carriage of the design work, from the schematic level to technical resolution and documentation, was shared in proportion to the size of each office, with Lyons acting as the principal consultant.

The building hosts the chemical engineering department, named for a notable alumnus: former Dow Chemical chairman and CEO Andrew N. Liveris. (Upon his retirement, Liveris, together with his wife Paula, donated $40 million to secure the construction of the building.) Underpinning the design generation for Banney and Lyon were three key themes: civic building-making, the culture of the end users, and the pedagogical imperatives of the brief. To use Banney’s phrase, the “relevant fodder” – which was ultimately synthesized into a holistic response – began with two looming precedents: UQ’s Great Court, with its Forgan Smith tower and sandstone ambulatory, and the John Andrews-designed brutalist building that previously held the faculty. The architects’ aim was to translate their reading of the Great Court into a kind of contemporary twin. Specifically, they have drawn upon references such as the veining and colour of the Great Court’s sandstone to generate the external colour palette of the facade glazing. Further, the axial alignment of the new structure with the Forgan Smith tower will, the architects predict, become an apparent urban connection in future. The Andrews building served as a stimulating precedent, with the architects noting its qualities of staff–student adjacency, display of pragmatic engineering kit, and what they described as the alchemy of an “enjoyably compressed” faculty bursting at the seams.

The program is characterized by open connecting stairs, shared collaborative spaces, and blurred boundaries between learning, research and industry.

Image: Christopher Frederick Jones

The vertical form of the Liveris building takes cues from both campus forerunners, resulting in an urban strategy that occupies only half of the site proposed for use by the competition. Building up rather than out has created an energized, compact and legible object in the campus landscape, with the additional site area programmed as sociable garden space in what is otherwise a congested part of the campus. This move allows for the building’s main facade to be read as a whole, while its other faces are more obscured.

The interior of the building is joyful and engaging. The organization of the program is dictated by the Pilot Hall – a large, multistorey subgrade testing facility also present in the Andrews building, but hidden away. Here, the Pilot Hall is the key element around which everything else gravitates. The space is visible from the footpaths outside, immediately upon entering the building, and from almost all circulation spaces around and up the interior. Stacked above the Pilot Hall is a dynamic atrium. Proportionally compressed to be taller than it is wide, the atrium pulls one’s eyes up to the soft daylight emanating through coloured glass above, energized by John Portman-esque lifts whose mechanisms are celebrated through open display.

The atrium is one moment where creative tension between Lyons and M3 may exist. Having experienced a number of civic/educational buildings by each practice, I notice that they take a distinctly different approach to collective vertical circulation. A typical M3 building, such as the Creative Learning Centre at Brisbane Girls Grammar School, employs the atrium as a collective experience to be shared while traversing stairs and walkways; by contrast, the RMIT Swanston Academic Building by Lyons eschews the singular atrium for more discrete and episodic experiences. In the Liveris case, the atrium is “both/and”: a central coherent space punctuated by a dynamic interplay of stairs, floating cubbies, and visual slices non-orthogonal to the plan. It works – evidenced during my visit by a high degree of student use on all levels of the building – as a set of “sticky” spaces to study, socialize and learn. On the theme of pedagogy, it brings clarity to the diagram of stacked functional spaces. One can see straight into and through laboratories to the campus and the city beyond, with the programmatic changes of use highlighted by shifts in colour as one ascends, in a manner that jettisons any sense of hierarchy. Here, engineering is fun, accessible and inclusive, which is indeed a triumph.

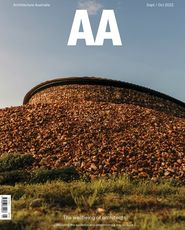

Building up rather than out has left a significant proportion of the site as green space – a rare commodity in this part of the campus.

Image: Christopher Frederick Jones

Generated from a genuine collaboration between architects who practise in the service of ideas, the Andrew N. Liveris Building invites enquiry from the moment one sees it. It is a building asking to be read, with the occupant accumulating a set of direct, contextual and digestible anecdotes rendered through form, material and colour. Highly technical and functionally demanding spaces are cleverly and efficiently blended to deliver an asset that the university can purpose for a range of pedagogical needs. Robust and frank detailing, such as in handrails, stairs and other direct moments of user engagement, culminate in an unpretentious yet bold, sophisticated composition to be interpreted and enjoyed.

— Chris Knapp is the research director of Building 4.0 CRC and an honorary professor at Bond University, where he served as head of the Abedian School of Architecture. He sits on the AASA Climate Action Committee and is a director of the Gold Coast design practice Studio Workshop.

Credits

- Project

- Andrew N. Liveris Building, The University of Queensland

- Architect

- Lyons Architecture

Melbourne, Vic, Australia

- Architect

- m3architecture

Qld, Australia

- Consultants

-

Acoustic & ESD consultant

AECOM

Certification and DDA PLP Building Surveyors and Consultants

Civil, structural and facade engineer AECOM

Electrical and services engineer AECOM

Fire safety engineer Omnii

Hazardous goods consultant AECOM

Landscape Lat27

Project manager Turner & Townsend

Quantity surveyor AECOM

Signage and wayfinding Büro North

- Aboriginal Nation

- Built on the land of the Turrbal and Jagera peoples

- Site Details

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Category Education

Type Universities / colleges

Source

Project

Published online: 27 Sep 2022

Words:

Chris Knapp

Images:

Christopher Frederick Jones

Issue

Architecture Australia, September 2022