The World Bank forecasts that, by 2030, seventy percent of the Chinese population will live in cities. This estimate confirms that the fast urbanization that has characterized the country’s development over the last few decades is expected to continue – in 1978, only 18 percent of Chinese citizens lived in cities, but by 2015, that number had climbed to 56 percent.1 Booming Chinese urbanism has offered numerous and significant working opportunities to Australian architectural practices, whose presence in China has increased steadily over the last four decades. The service sector is now a larger contributor to Chinese GDP than manufacturing – a major driver of economic growth – and China is Australia’s largest services export market, worth $15.8 billion in 2017 (18.7 percent of Australia’s total services exports).2 In 2015, the China– Australia Free Trade Agreement (ChAFTA) was passed, facilitating new or significantly improved market access. 3

Australian architectural practices have been taking advantage of steadily improving bilateral relationships between Australia and China, and continue to demonstrate responsiveness to the extreme dynamism that characterizes the Chinese design and construction market. The high degree of flexibility displayed by Australian architectural firms is certainly appreciated in a country in which rapid urbanization exceeds the availability of local professionals. Austrade, Australia’s lead government agency for international trade promotion and investment attraction, reports that there are currently more than forty Australian architectural practices working in China and more than three hundred firms that have won work in the country.4 In China, most projects by Australian firms that go beyond the schematic design phase need to be completed in collaboration with a Local Design Institute (LDI), and project sources vary from traditional tender processes to competitions and recommendations from existing relationships. Compared to a decade ago, Australian offices are now operating in China well beyond the major coastal centres of Shanghai, Shenzhen and Beijing. Progressively, they have penetrated mainland China, with a large number of recent projects in emerging cities such as Chongqing, Chengdu, Zhuhai, Xi’an, Tianjin and Nanjing, as well as in some rural areas.5

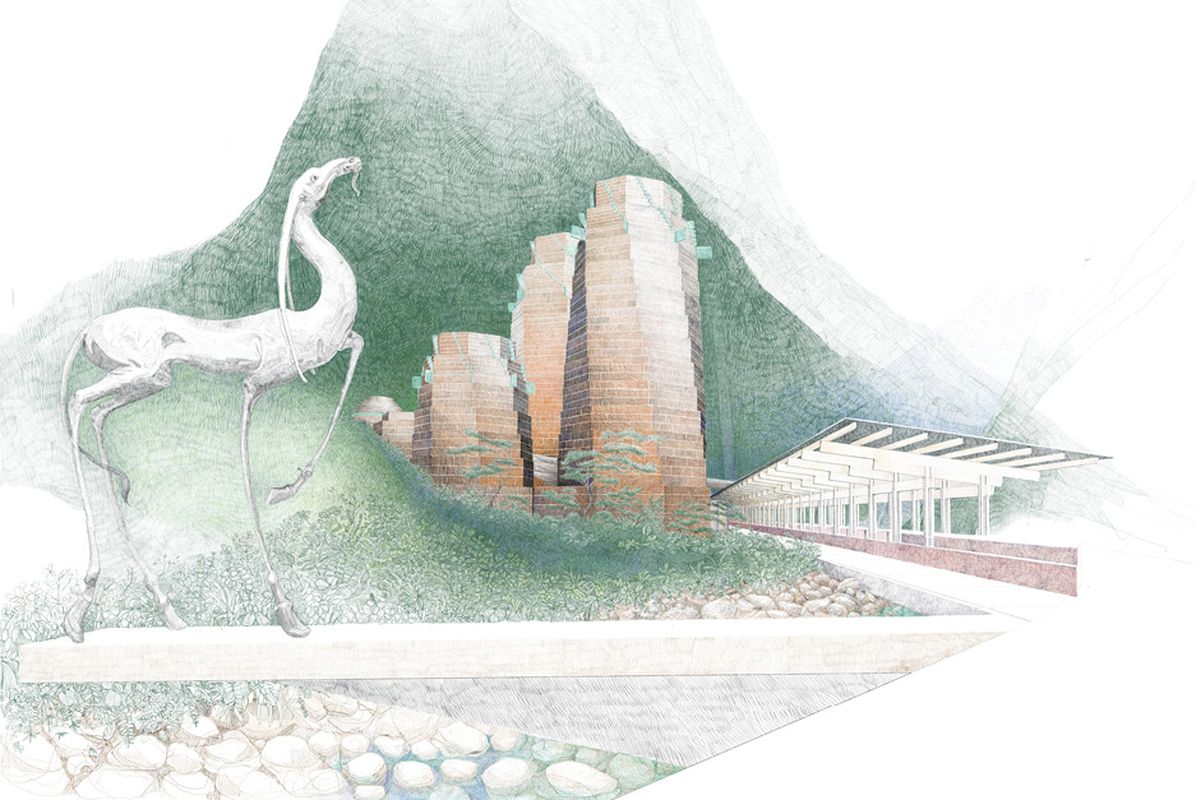

Led by Australian designers, Gossamer is proposing projects like the Jing River waterfront that celebrate the site’s history while also emphasizing the vitality of good design.

Image: GVL Gossamer

The largest of these practices are global firms: architectural offices that started their activity in Australia but are now operating at a multinational level, with projects and office locations across the globe, including in China.6 Among them are Hassell, Populous and Woods Bagot. These firms have staff numbers of more than 150 people and a recognized design capability to manage and deliver substantial projects in a limited amount of time to international standards. They typically leverage their size, experience and capabilities towards specialist projects. Populous, for example, has completed more than fifty projects in China, including large arenas, stadiums and other entertainment venues.7

Brearley Architects and Urbanists (BAU), Jackson Teece, Cox Architecture, Group GSA and Denton Corker Marshall (DCM) are some offices that work primarily from Australia yet earn substantial commissions in China. Although not operating at the same scale as the global firms listed above, they have been involved in producing a number of significant works overseas. For instance, BAU, which has offices in Melbourne and Shanghai, has carried out a wide range of projects in China and has a deep understanding of the character of the fast-growing Chinese cities in which it brings innovation.8 Similarly, Jackson Teece has recently proposed five projects for senior communities in China and is establishing a reputation in that country for aged-care architecture.

Other Australian firms undertake occasional work in China on a project-by-project basis. These include Melbourne- based John Wardle Architects and Sydney- based Candalepas Associates. These firms, which are place-focused, design considered projects that engage with the local environment and history. In response to a growing appreciation and demand for quality design in China, astute clients are recognizing the value of this authentic and crafted approach.

Beyond more traditional offices, hybrid ways of practising have also emerged. This was the case with PTW, one of Australia’s oldest architectural firms, with recognized expertise in tall buildings and architect of the famous “Water Cube” National Aquatics Center, completed in 2008 for the Beijing Olympics. In 2013, PTW was acquired by China Construction Design International (CCDI), a Chinese architecture and engineering consulting firm that employs around four thousand staff.9 The acquisition has enabled PTW, now based in China and Australia, to step up its regional reach while resolving pre-existing cashflow problems. Design practice Gossamer operates under a different strategy of partnership. Led by Australian designers, Gossamer is a multidisciplinary design division of the GVL Group, one of China’s leading LDIs. This operational approach is based on the cross-pollination between international and local capabilities and has led to projects such as LOOP (2019), one of Shanghai’s first community consultation urban regeneration projects.

Using a winding sky deck, Hassell ties together cultural buildings and parklands in Shenzhen in its Silk Road Corridor design.

Image: Hassell

In 2014, the Chinese government released a national urbanization plan to address internal migration and respond to issues resulting from rapid urban development. These included strategies to reduce congestion and pollution, to improve the quality of urban development and architecture, to increase public green space, and to preserve historical buildings and enhance “city character. ”10 This shift toward a more sustainable approach, attention to lifestyle and increased sophistication of the built environment coincided with Chinese president Xi Jinping’s appeal for less “weird architecture” to be built in the country. China’s construction boom had provided opportunities for many international practices to realize projects that couldn’t be completed elsewhere, but this now looks set to change.11 In 2016, China’s State Council released new urban planning guidelines, which stated that “bizarre architecture that is not economical, functional, aesthetically pleasing or environmentally friendly” would not be built in the future.12 This new focus on a healthier built environment, increased wellbeing and buildings with long-term purpose for Chinese cities will be familiar to architects from Australia, where urban design research is active and responsive to the evolution of technologies, lifestyles and expectations.13 Many Australian practices are internationally recognized for their considered, sensitive relationship to landscape and history, and for crafting attentive solutions for contemporary life.

The projects carried out in the last decade by Australian firms operating in China clearly reflect this change of perspective. The recent Zhuhai Tennis Centre (2015) by Populous is the first undercover international-standard tennis facility built in China. Recognized as an outdoor tennis centre, the stadium shelters spectators while allowing natural breezes and filtered sunlight to permeate the five-thousand-seat arena.14 Another example is the Kaida Science Park in Dongguan by Denton Corker Marshall (due for completion in 2021), where multiple sustainability features will be integrated into the architecture. The focus of the building is on cross-ventilation and airflow, creating a landscaped city room and using shading devices to reduce thermal load. BAU’s Duolan Dong Dong Mixed Use Complex (2012) in Hangzhou combines landscape architecture with architecture and urban design. The architects explain that the project’s green roof “provides the city with a unique public open space [and] creates social, entertaining, community garden and recreational space for occupants.”

Denton Corker Marshall’s design for the Kaida Science Park in Dongguan integrates multiple sustainability features into the architecture.

Image: Denton Corker Marshall

This aligns with another developing trend inw China focused on preserving the quality of both the built environment and the natural context. Hassell’s Silk Road Corridor, a competition concept in Shenzhen, is a multi-layered project that uses a winding sky deck to tie together cultural buildings and parklands in one urban destination. While echoing acclaimed elevated linear parks such as New York’s The High Line and Seoul’s Seoullo 7017, the project in fact refers symbolically to the Silk Road, an ancient trade network that connected China with the West. It emphasizes the importance of good design with a strong narrative thread. Likewise, Gossamer’s competition proposal for a stretch of waterfront along the Jing River (2019) is a well-balanced interaction of architecture and natural landscape, conceived as an ecological park that would turn Xi’an’s new Xixian area into a vibrant and environmentally sensitive district. The proposal “celebrates the site’s history at the origin of the Silk Road through strategies that tap into ancient and enduring histories of traditional architecture, merchant trade and agricultural innovation.”

Important examples of smaller scale work with a keen sensitivity to place are the Chinese projects completed by Kerry Hill Architects, an Australian practice with offices in Singapore and Perth. The stunning Amanyangyun resort in Shanghai (2017) highlights a response that establishes, according to the architects, “a deep-rooted sense of connection to place and culture.” Twenty-five Ming and Qing Dynasty houses were rescued from the rising waters of a new dam in Jiangxi Province and relocated to Shanghai. Years of conservation and preservation efforts, along with appropriate interventions, has resulted in a twenty-first- century hotel “imagined as a contemporary walled village in a forest.” (For a review of Amanyangyun Shanghai, see page 74.) Another project that synthesizes the Australian subtle approach to nature and reinterpretation of local culture is the proposed Jade Museum by Candalepas Associates in La Mei Valley, Hubei. Emphasizing the connection to the surrounding landscape and universal geometries, the project aims to create acute awareness of the similarities and differences between nature and art, while engaging with multiple sensory experiences. These qualities are highlighted through a sublime drawing by Mark Gerada (left), showcasing sensitivity to culture, history, place and contemporary design.

– Paul Violett is a recent graduate of architecture from The University of Queensland. He currently works for Arcke, a small residential practice in Brisbane.

– Silvia Micheli (PhD, Università Iuav di Venezia) is a lecturer at The University of Queensland, where she teaches design. Her research investigates global architecture and cross-cultural exchanges in the architectural and urban context.

Footnotes

1. “Architecture and design to China: Trends and opportunities,” Australian Trade and Investment Commission website [undated], austrade.gov.au/Australian/Export/Export-markets/Countries/China/Industries (accessed 28 October 2019).

2. “ChAFTA fact sheet: Trade in services,” Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade website, August 2018, dfat.gov.au/ trade/agreements/in-force/chafta/fact-sheets/Pages/ chafta-fact-sheet-trade-in-services.aspx (accessed 28 October 2019).

3. For an analysis of the impact of the agreement on architects, see Linda Cheng, “What does ‘Free Trade’ with China mean for Australia’s architects?,” ArchitectureAU. com, 30 November 2015, architectureau.com/articles/ what-does-free-trade-with-china-mean-for-australias- architects (accessed 28 October 2019).

4. “Architecture and design to China: Trends and opportunities,” Australian Trade and Investment Commission website [undated] .

5. In October 2019, Cameron Bruhn and Paul Violett from The University of Queensland produced a report, Study of Australian Architecture in China , based on a taxonomic investigation of the extent and scope of Australian architects working in China. Facilitated by the Australian Embassy in Beijing and the Australian Consulate-General in Chengdu, the report looks at how projects designed by Australian practices in China have contributed to improving quality of life among Chinese citizens.

6. On the organization of large Australian architectural practices operating in China and globally, see Sandra Kaji-O’Grady, “Australian exports,” Architecture Australia vol 106 no 4, 49–50.

7. “The influences on sport and design in China and how it differs with the West,” Populous website, 19 August 2016, populous.com/influences-sport-design-china-differs-west (accessed 28 October 2019).

8. BAU directors James Brearley and Fang Qun published the book Networks Cities (China Architecture and Building Press, 2010) and, in their work, they attempt to counter tendencies towards segregation of programs and land-use in current Chinese planning.

9. Michael Bleby, “How a Sydney architecture firm designed a Chinese future,” The Australian Financial Review, 24 May 2014, afr.com/companies/infrastructure/how-a-sydney- architecture-firm-designed-a-chinese-future-20140524- iupki (accessed 28 October 2019).

10. Wade Shepard, “The impact of China’s new urbanization plan could be huge,” Forbes , 14 March 2016, forbes.com/ sites/wadeshepard/2016/03/14/the-impact-of-chinas- new-urbanization-plan-could-be-huge/#61aa68306673 (accessed 28 October 2019).

11. “Debate after China’s Xi demands end to weird architecture,” The Straits Times, 16 October 2014, straitstimes.com/asia/east-asia/debate-after-chinas- xi-demands-end-to-weird-architecture (accessed 28 October 2019).

12. “China looks to regulate city growth,” The People’s Republic of China State Council, 22 February 2016, english. www.gov.cn/news/top_news/2016/02/22/content_ 281475294306681.htm (accessed 28 October 2019).

13. Lucile Jacquot, Karine Dupré and Yang Liu, “China can learn from Australian urban design, but it’s not all one-way traffic,” The Conversation, 14 July 2019, theconversation.com/china-can-learn-from-australian- urban-design-but-its-not-all-one-way-traffic-115905 (accessed 28 October 2019).

14. “Zhuhai Tennis Centre,” Populous website, populous.com/ project/zhuhai-tennis-centre-2 (accessed 28 October 2019).

Source

Discussion

Published online: 2 Apr 2020

Words:

Paul Violet,

Silvia Micheli

Images:

Angelo Candalepas (design), Mark Gerada (drawing),

Denton Corker Marshall,

GVL Gossamer,

Hassell

Issue

Architecture Australia, January 2020