Any house – even a hut – you build embodies a history, that of its own building. For a public institution, the actual business of building may have a complicated backlog of debates and even quarrels that have shaped it. After it is built, time will alter and modify it, year by year.

— Joseph Rykwert on David Chipperfield’s Neues Museum (2009) 1

The curious in-between ground that school buildings occupy is both private and public – and at the same time, neither. Perhaps the Latin words communicare (“to share”) and communitas (the “community” or “kinship” that develops among people experiencing a rite of passage, such as a school cohort) might best describe the state that binds a school together.

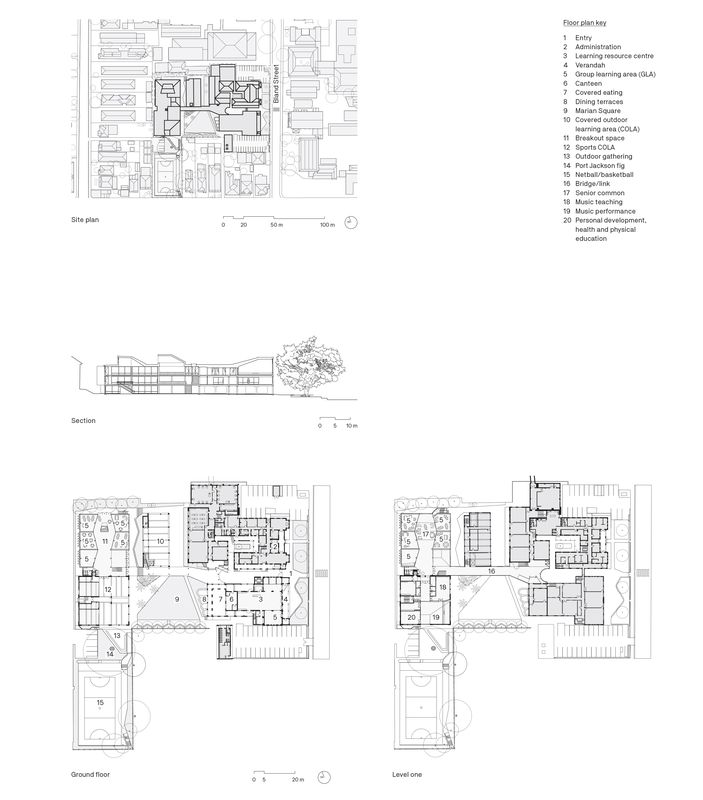

The campus of Bethlehem College, located in Ashfield in Sydney’s inner west, was a complex conglomeration of buildings that had been collected on the site since 1881, when the Sisters of Charity established a convent school here. Rachel Neeson, a former student of the school and now director of architecture practice Neeson Murcutt and Neille, was approached to reconsider the school – its communitas – which had become tangled and compromised by built additions made over the years. The campus lacked a meaningful centre and had become a series of well- meaning yet disconnected outtakes that provided little in the way of a cohesive school campus experience.

Sometimes you need to take something apart to understand how it works. Through a graphic analysis of both the existing built form and the landscape, Neeson Murcutt and Neille identified the plaques and ligatures that blocked and bound the potential of the campus and, in turn, recognized a strategy that would free it up and create a new arrangement grounded in the landscape.

The brief involved re-creating a meaningful centre for the school (Marian Square) – a physical heart to reflect the heart of the community.

Image: Brett Boardman

For a variety of reasons, the school’s built form had congregated around the middle of the site, leaving open spaces stranded at the edges, where they were allowed to become peripheral. The design team set out to relink the school by bringing open landscaped spaces back to the centre of the campus arrangement. By removing an ageing building block from the site’s centre and introducing a new building at its northern corner, the architect has created a sextet of buildings that wraps around a new campus heart: a gently sloping lawn drawn in place of the removed building.

Linking the spaces was a critical part of the brief. Imperative to the reworked arrangement is the introduction of a new spine – a built element, neither internal nor external – that enables the various levels and spaces of the school to be, in Neeson’s words, “collected.” Along its southern edge, this spine also creates a three-sided cloister around the new school heart. Deft interventions to the edges of the existing buildings that flank the heart allow a continuous covered open space to wrap around all sides of the lawn. To the west, the rear of the original convent building has been cleared away to reveal a four-arch covered space replete with “fallen arches”: four brick plinths that project into the open space to form discrete seating platforms. Where detracting building elements have been removed, their “shadows” have been retained as simple rendered profiles painted in red oxide, creating a quiet background pattern that suggests where previous built form existed. To the east, the ground level of the refurbished Sophia building has been broken out to become covered outdoor space. This move also frees up the ground plane to invite a large Port Jackson fig, which for years had been growing behind the buildings, back into the centre of the school. No longer an adjunct, the space beneath the fig becomes an outdoor room – an extension of the covered outdoor spaces created throughout the revitalized school grounds.

The new spine provides a well-used undercroft area and reconnects the school’s buildings “with benevolence.”

Image: Brett Boardman

The fig is also an important aspect of the internal reconfiguration of the Sophia building, into which a large window opening has been added to give students in the new music spaces views through the tree canopy. The Sophia building’s roof plane has been pushed and stretched with expressive roof monitors that draw light in from above the predominant three-storey building datum of the north-western buildings. Additionally, sculpted external window screens admit light and ventilation on all sides of the building without compromising the amenity of its immediate neighbours.

The malleability of the spine structure is the bind that permits the rejuvenation of the existing school buildings. At one end, the spine acts as a gateway, drawing the student or visitor down between existing buildings. The glass facets of the spine’s concave upper storey draw the sky into an antechamber of sorts, from which the students peel off to their various lessons and purlieus. For the rest of its length, the spine allows all of the buildings to be reconnected with benevolence, as the spaces designed primarily for connection can also become spaces in which to gather together for both formal school events and informal day-to-day gatherings.

A large window in the music performance space offers views into the canopy of a significant Port Jackson fig tree.

Image: Brett Boardman

Adjacent to this new gateway, the reconfiguration of the original convent building houses the school’s new learning resource centre, which opens up onto the restored timber filigree verandah that, in turn, flows forward to a new forecourt wrapped with a profiled concrete bench. Pragmatically, this arrangement provides further outdoor learning space, while symbolically, it reconnects the school to the community, enabling the inclusive and diverse nature of the school to be publicly expressed rather than hidden away behind fences and walls.

Socrates’ much-repeated saying, that “Education is the kindling of a flame, not the filling of a vessel,” may well be applied to educational architecture as well. Understanding that buildings aren’t absolutes, but rather – much like education itself – exist as vicissitudes, has enabled Neeson Murcutt and Neille to preserve a sense of communitas and embody the school’s own history through the act of (re)building. As some aspects of the school are uncovered while others are adapted and reimagined, the sense that the school has of itself stays alight, open to learning, change and adaptation.

1. Rik Nys and Martin Reichert (eds), Neues Museum Berlin (Cologne: Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther König, 2009).

Credits

- Project

- Bethlehem College

- Architect

- Neeson Murcutt and Neille

Potts Point, Sydney, NSW, 2011, Australia

- Project Team

- Rachel Neeson, Giles Parker, Nicole Cussack, Joe Grech, Davin Turner, AK Risnes

- Consultants

-

BCA and fire engineering consultant

BCA Logic

Hydraulic engineer Niven Donnelly and Partners

Landscape architect Sue Barnsley Design

Planning Mersonn Pty Ltd

Quantity surveyor Wilde and Woollard

Services engineer Cundall (stage one), BSE (stage two)

Structural engineer SDA Structures

- Aboriginal Nation

- Built on the land of the Gadigal and Wangal peoples of the Eora nation.

- Site Details

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Category Education

Type Universities / colleges

Source

Project

Published online: 19 Jul 2021

Words:

David Welsh

Images:

Brett Boardman

Issue

Architecture Australia, March 2021