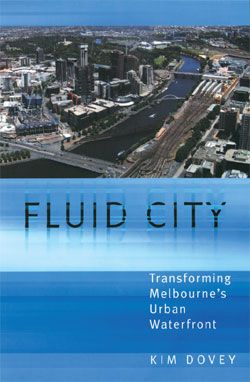

FLUID CITY

TRANSFORMING MELBOURNE’S URBAN WATERFRONT

Kim Dovey with co-authored chapters by Leonie Sandercock, Quentin Stevens, Ian Woodcock and Stephen Wood. UNSW Press, 2004. $59.95.

This book is concerned with the wholesale change and regeneration of entire precincts initiated through political upheavals, economic shifts, changing technology or cultural evolutions. In recent years, most Australian cities have been transformed as attitudes to waterfront real estate change, combined with the timely availability of great swathes of waterfront industrial land that have outlived their economic life.

Fluid City takes the transformation of Melbourne’s three urban waterfronts – the Yarra River, Melbourne Docklands and Port Phillip Bay – as its subject. These are discussed under the general titles of Riverscapes, Dockscapes and Bayscapes. The bulk of the chapters run as chronological narratives, laying down a well-researched account of the process of change for each precinct. The value of documenting these processes cannot be underestimated, as it is this knowledge that often becomes lost or blurred over time.We tend to recall only the major physical events – “what was there” and “what is there” – while the details of how we got there fall out of collective memory.

Intermingled with these narratives are theoretical discussions, some co-authored, on urban design. The idea behind this mix is sound, but the chapters sit uneasily together and ultimately this feels a little like two books spliced together. Dovey points out that “without a theory base, public debate on urban design will be reduced to opinion”. He is absolutely correct. However, the theory presented here is unlikely to be debated in public. Many readers will feel inadequate in their lack of familiarity with the many urban theorists referenced, and will struggle to fully comprehend what is written.

This book places special emphasis on the notion of a “fluid city” – fluid as in a state of change and fluid as in waterfront. But the analysis suffers a little from the penchant for looking for theoretical relationships through the convenient use of language. The “fluid” metaphor is heavily pushed, with “flow” serving to describe all forms of transformation and movement, while a banal correlation is drawn between waterfront and computer “ports”, both of which provide a conduit to the world.

Yet the discussions underpinning Fluid City are not particular to waterfronts. They are equally relevant to the urban renewal of other tracts of land, such as landlocked industrial areas like Alexandria in Sydney, or high-rise public housing estates in Redfern.

The narrative is highly informative, but much of it is also highly opinionated. Critiques of built works are often made blithely, as if there is an assumption that the reader already shares the writer’s opinion. Perhaps this is because the book is trying to cover so much territory – there is not the space for sound critical analysis – but it portrays a point of view that, at times, seems dogmatic.

The public/private debate is at the core of much of this book, and is comprehensively discussed. It corresponds with the privatization push that has been the mantra of successive state and federal governments, both Coalition and Labor. These ideological discussions about the public interest, public funding, public land – their relationship to political and private interests and the complicity of architects in the promotion of such interests – are the book’s real strength.

ANDREW NIMMO

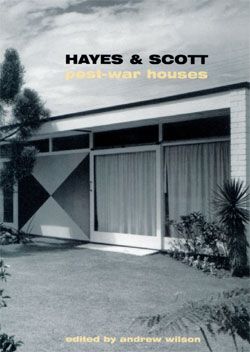

HAYES & SCOTT

POST-WAR HOUSES

Edited by Andrew Wilson. University of Queensland Press, 2005. $30.

The house occupies a special place in the Australian architectural imagination, and the postwar period was crucial in forming this. The pragmatics of housing shortages and the ideals of making a home in the new world, far from the ravages of war, combined with government policy, public interest and architects’ commitments to privilege the house. The growing affluence and associated rise of “lifestyle” in the late fifties and early sixties both changed and reinforced the emphasis on the house. To understand the role of the house in Australian architecture today, we need to understand the postwar period in all its complexity, particularly as contemporary designers continue to revisit Modernist forms and styles.

This small volume makes a valuable contribution to our knowledge of the period and the ongoing contemporary interest in the house in two key ways. Firstly, by inviting us to reconsider the domestic oeuvre of Brisbane practice Hayes & Scott, it brings a body of work, largely unknown to readers outside Brisbane, into the public realm. As Jo Besley points out, the progress of Hayes & Scott’s domestic work closely mirrors the general postwar housing situation, which makes this book particularly useful. Secondly, the essays expand the ways we might approach architecture and its history.

The book begins with an outline by Andrew Wilson and Angela Reilly of the partnership between Eddie Hayes and Campbell Scott, their influences and the characteristics of their work. This is followed by a catalogue of projects.

A series of essays then discuss particular aspects of the work through more specific situations. Julian Patterson considers the murals of the Harvey Graham house, taking the opportunity to discuss postwar use of colour and pattern, and to suggest a complex interplay between local circumstance and international influence.

Elizabeth Musgrave’s detailed analysis of the Jacobi House also offers an alternative to stories of regional stylistic development, discussing instead the close relationship between structural and spatial possibilities.

Alice Hampson follows the lead of American historian Alice Friedman to consider the role of the independent woman client in the production of modern architecture. She tells the fascinating story of Ethne Pfitzenmaier, who, in articulating her particular domestic requirements, provided an opportunity for Eddie Hayes to produce two of his most significant houses.

Jo Besley’s beautifully written piece attends to what she calls the “secret history of modernism”, the profession’s work in popular housing, through speculative houses, display homes, homes for returned servicemen and so on. In Hayes & Scott’s case this included the design of a “dream home” organized through a Woman’s Day competition. The discussion is both engaging and highly relevant at a time when many have forgotten Modernism’s ethical imperatives.

The book closes with Igea Troiani’s use of interviews to address the idea of legacy and the ways that architectural ideas are taken up and transformed by succeeding generations.

The book is generously illustrated. However, given the importance of the “splash of colour” in Hayes & Scott’s work, it is disappointing that there are no colour images – undoubtedly an effect of economics.

The authors point out that although Hayes & Scott were locally influential, they have received little critical attention. This volume, then, is both timely and a little overdue.

JUSTINE CLARK