Hill Thalis Architecture + Urban Projects, Paul Berkemeier Architects and Jane Irwin Landscape Architecture

Lippmann Associates, Richard Rogers Partnership, Martha Schwartz and Lend Lease

Lend Lease design, Taylor Cullity Lethlean, JBA Urban Planning and The People for Places and Spaces

Project, Hargreaves Associates and Morphosis

PTW, EDAW and Advanced Environmental Concepts

A selection of images from the winning scheme by Hill Thalis, Paul Berkemeier Architects and Jane Irwin Landscape Architecture. Plan.

A sketch of the “drunken piles”, hardwood timber piles that would lose balance in the harbour’s tidal waters.

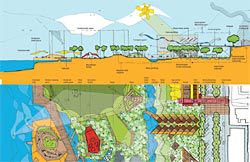

Tidal wind and solar power are harnessed to make a row of tidal cranes.

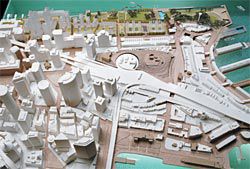

Elevational view of the model.

Bird’s-eye view of the model, showing site strategy and urban context.

The landscape-driven entry from Project, Hargreaves Associates and Morphosis.

The scheme from PTW, EDAW and Advanced Environmental Concepts aims to create a flexible space that is informed by local cultural values and memories of Millers Point and Sydney.

The urban waterfront design from Lend Lease design, Taylor Cullity Lethlean, JBA Urban Planning and The People for Places and Spaces.

The Lippmann Associates, Richard Rogers Partnership, Martha Schwartz and Lend Lease proposal integrates water and vegetation throughout. The plan and section show the scheme’s island precinct.

The lure of scale. Elizabeth Mossop reviews the outcomes of Sydney’s controversial East Darling Harbour competition.

As designers it is very hard to resist the lure of urban redevelopment on the scale of East Darling Harbour’s 22 hectares, but before looking at the competition and its outcomes it is important to question some of its underlying premises. Why does all waterfront renewal in Sydney have to be for residential and commercial use only? Will the city be improved when the waterfront is primarily residential? Can Botany Bay support further port development without unacceptable environmental degradation? Does it make sense to ship goods to Port Kembla that then have to be trucked to Sydney? Why couldn’t the East Darling Harbour site be redeveloped as a world-beating eco-industrial park, with a working port facility, commercial use and increased open space, connected into an integrated system of transit?

Underlying planning decisions of this kind require a longer political view than is currently being exhibited, and the ability to resist the immediate financial returns that can spell career success for individual politicians but diminish the public benefit in the long term.

If we look at the competition as it was framed, the finalists and the brief also need to be seen in the context of Sydney’s earlier waterfront redevelopments – Circular Quay, Darling Harbour, Cockle Bay, King Street Wharf, Pyrmont and Woolloomooloo Bay – as well as earlier waterfront developments and proposals, such as Seidler’s for Blues Point and the long-established Domain and Botanic Gardens. These earlier works suggest the vital importance of connection to the urban context, integration with viable public transit, incremental development and the importance of a strong public domain. They also point to the need to find identity for major developments beyond theming. The value of the Domain and Botanic Gardens, and the headlands in Sydney Harbour National Park, show that it is impossible to overestimate the significance of providing major urban parkland to the future inhabitants of the city. The winning scheme, from Hill Thalis Architecture + Urban Projects, Paul Berkemeier Architects and Jane Irwin Landscape Architecture, deals with many of these issues very effectively.

A key issue in the evaluation of the competition results has been the question of how the strategic plan can be translated into reality, its “deliverability”. This seems to have been one of the major determinants in the success of the winning scheme. Given the Australian track record on the implementation of visionary design ideas, and the conservative design climate prevailing, perhaps we should be totally focused on this factor – its ability to be implemented in this place and at this time. There seems to be a parallel with the pragmatic approach taken with many of the Olympic projects, where a conservative financial package often bested design quality and environmental innovation.

Perhaps this is the price of living in the real world – we have to abandon youthful ideals and can no longer hold out for visionary solutions – but it also smacks of a lack of faith in the ability of designers to really solve complex and intractable urban problems innovatively. Perhaps it also reflects the concentration of bureaucrats and other non-designers on the jury.

Alternatively, it could be argued that, given our propensity to grind distinctive and innovative design down to mediocrity, and to kill bureaucratically the unique elements of major projects in the name of “market forces”, we should select schemes where the design ideas are robust enough to survive this apparently inevitable process. It is incumbent on the design community to fight this powerful undertow through public discourse and better communication of ideas.

The finalists illustrate a spectrum of design approaches in terms of expressive form-making and at the scale at which design intention becomes apparent. These range from big gestural moves at the urban scale, as in the Project/Hargreaves/Morphosis and the Lippmann/Rogers/Schwartz/Lend Lease schemes, to proposals where this may emerge at the site scale, as in the Hill Thalis/Berkemeier/Irwin scheme. The jury and some commentators seem to suggest that the former approach is less workable than the latter, but this precludes many exciting alternatives. If all new urban form is to be generated only by response to the existing context we will never be able to fully take advantage of opportunities missed in the past, new technological wizardry or new conceptions of city life.

The brief refers to the unique character of the city and of the site a number of times. Entrants were asked to “capture a sense of what Sydney is now and what is appropriate development for the city in the 21st century” as well as to “recognise the unique qualities, significance and prominence of the site on Sydney Harbour and use buildings and landscape to capture and enhance them”. It is difficult, however, to read a tangible sense of site and place into most of the finalists’ schemes. This relates to the scale of the project and is perhaps inevitable given the requirements and limitations of the competition. But I believe that quality and character should be more important in determining the success or failure of individual proposals.

Sydney’s character is defined by its landscape. The city’s water edges – harbour, beaches, rivers or bays – compose a unique and varied urban landscape. The significant presence of “natural” bushland and parkland throughout the city, especially on headlands in close proximity to the CBD, reinforces the landscape presence. The other unique aspects of Sydney’s character relate to the importance of outdoor living, sports and recreation and a certain playfulness and irreverence in the most successful public spaces.

The competition brief recognized the real opportunity for the proposals to create major new urban parkland. As the city becomes denser, housing ever-increasing numbers of residents, workers and tourists, the value of urban open space increases exponentially, particularly on the waterfront. The future significance of the parkland is not only about size, although a certain generosity of scale is mandatory. More important is the quality of the parkland, the character of its spaces, its accessibility and connection, its activation by a mix of uses, and so on. These issues of quality and character suggest the desirability of strongly iconic landscape moves.

The finalists range from contextual urbanism to big architectural moves to landscape dominance. The winning scheme from Hill Thalis Architecture + Urban Projects, Paul Berkemeier Architects and Jane Irwin Landscape Architecture is perhaps the most urban of the finalists, being driven by an intelligent understanding of the urban context. The clarity of the plan is very strong, with its wedge of development anchored in the CBD and the complementary wedge of parkland expanding to the headland. It is a very workable solution and there is great potential in the development of the public open space. This is all to the good, as it seems to be crying out for more flamboyant treatment of the water and its edge, as well as greater amplification of the headland within the major open park to the north.

Also strongly contextual in form but more architectural, with its great wedge of buildings on the waterfront, the scheme from PTW, EDAW and Advanced Environmental Concepts fails to capitalize on the site’s potential by removing the major linear park from the waterfront. The repetitive nature of its urban form, while seductive in plan, suggests a potentially monotonous experience. The separation of the wall of buildings from the city fabric also casts doubt on the ability of the development to be vibrant economically and socially. There are some attractive moves, such as the Millers Point Meanders, but the landscape seems somewhat generic and dominated by the architecture.

The most architectural of the finalists is the scheme by Project, Hargreaves Associates and Morphosis, although the sheer scale of the open space is magnificent, with 90 percent of the site covered by park. The boldness of the building forms creates a very idiosyncratic urban pattern in the residential district. This dominates and seemingly detracts from the urban quality of the southern precinct. This is a risky competition strategy in Sydney because it suggests the need for one architect to realize the residential development, and the hand of a single development entity to implement the vision. However, the central sports park in proximity to the CBD suggests the potential to spur surrounding development and really enliven a new city precinct. The further development of the landscape could make this a most compelling scheme.

The animation of the Lend Lease design/Taylor Cullity Lethlean/JBA Urban Planning/The People for Places and Spaces project has a lovely textural quality that emphasizes the integration of water and vegetation through the precinct. The singularity of the waterfront promenade and its artificial theming is a little too resort-like, and reminiscent of Darling Harbour, requiring greater connection into the urban fabric. Subsuming much of the built programme within the landscape in the northern half of the site is an interesting strategy that ultimately seems to work against the creation of a really spectacular urban park.

The Lippmann Associates/Richard Rogers Partnership/Martha Schwartz/Lend Lease proposal is great fun. Characterized by Martha Schwartz’s distinctive patterning and form-making, the landscape and water define three distinct site zones: a highly urban link to the CBD, a central park flanked by housing and full of diverse programme, and a major recreational beach park to the north. Substantial bodies of water connect the project to the harbour and support water-based activity, referencing many of the city’s most loved outdoor places. This scheme was commended by the jury and, while there are clearly technical problems with some aspects of the proposal, in many ways seems a more obvious winner because of the vitality of its programming and the potential of its urban landscapes.

The real test will be whether the competition leads us to the most successful redevelopment of this site, and whether the winning scheme will be robust enough to withstand the mediocratizing forces that will be applied at every step of the approval, development and implementation processes. But if you believe in the transformative power of physical design to dramatically change cities for the better and the responsibility of public projects to take a leading role in design and environmental innovation, then perhaps the jury could have been more courageous.

›› ELIZABETH MOSSOP IS DIRECTOR AND PROFESSOR OF LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE AT LOUISIANA STATE UNIVERSITY.

THE FULL ENTRIES CAN BE SEEN ONLINE AT WWW.EASTDARLINGHARBOUR.COM.AU