The small country town of Yackandandah in north-east Victoria is located at the confluence of two creeks. The area’s Traditional Custodians were dispossessed by European settlement, which was spurred during the mid-nineteenth century by a gold rush, and the town’s population quickly swelled to a high of 3,000 in 1862 (today, the population is around 2,000). This brief surge left a built legacy of weatherboard shopfronts that remain today, lining the main street and anchored by a pub at each end, the whole nestled into a valley surrounded by picturesque hills.

Chris Gilbert, a founding director of architecture practice Archier, grew up in Yack (as it’s known by the locals). As a child, he often rode his bike over the rise that now contains Court House: a sloping site, located behind the 1864 courthouse, a five-minute walk from the main street and across the road from the public pool. Court House is Archier’s second house in Yack, but the award-winning Sawmill House, which the practice designed for Chris’s brother Ben, is tucked away from view. Now, Archier had the chance to make a more public contribution to Yack, and Chris leapt at the opportunity.

The home’s structure is used as both texture and ornamentation. Artwork: Mieczysław Górowski.

Image: Rory Gardiner

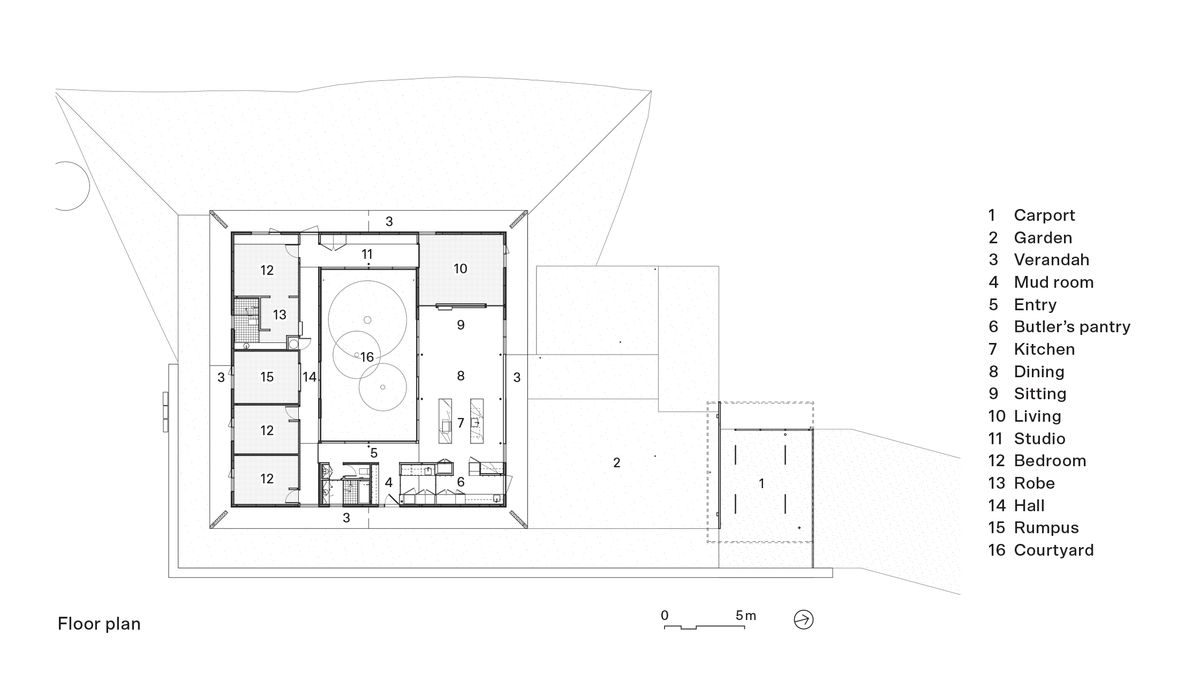

The design of Court House responds to the prominence of the site with an elegantly simple courtyard plan. North-facing windows draw winter sunlight into living spaces, and the central courtyard provides practical separation between public and private zones, while also pushing bedrooms away from the street and providing private outdoor space. This clear and rational organization is paired with minimalist details such as a flat roof, long verandahs and cleverly concealed gutters. Given these crisp architectural details, you would be forgiven for thinking that Archier is primarily interested in refining the craft of construction for aesthetic ends. According to Chris, that isn’t Archier’s only – or even most important – goal. “It’s as much working from methodology as it is aesthetic,” he says. “The way the roof works with the glass plane, for example, is about maximizing the system’s potential.”

Designed for clients who are passionate about environmental sustainability, the house follows Passivhaus principles that prioritize highly insulated, highly sealed buildings and low energy consumption. Archier has employed Structural Insulated Panels (SIPs), prefabricated sandwich-like panels composed of thick polystyrene lined with sheets of Oriented Strand Board (OSB, a form of chipboard). The SIPs lock together like Lego, forming structural walls and a rigid roof plane. SIP systems drastically reduce the need for steel and conventional timber framing, speeding up construction on site. Archier gave the OSB a simple coat of white paint internally, elevating the utilitarian material to textured decoration. Vertical timber cladding externally is sourced from local species. Angled concrete blades act as columns for the otherwise cantilevered verandahs, and, for a house comprised primarily of lightweight polystyrene (especially so, if you include the insulation embedded into the floor slab), the heavy corners provide a welcome tactile and visual gravitas.

Angled concrete blades form columns at the edge of the verandah, adding heft and gravitas.

Image: Rory Gardiner

At the same time as orienting the house for north light and squeezing it between the invisible constraints of a pair of easements, Archier aligned the perfectly square plan with the brick courthouse in front, giving the landmark a clean, contrasting backdrop of timber and glass. The local council, however, took some convincing. Chris was determined to demonstrate an alternative way of responding to landscape, to build something unapologetically contemporary that wasn’t simply “recessive to the traditional architecture of the area,” as the heritage advisor had recommended. As Chris asked him at the time, “What is it that you’re trying to preserve?” Instead of designing something that disappears from view or defers to a colonial past that was defined by violence and the displacement of Indigenous people, he wanted to do something that represented his generation’s values and aesthetic; something open and sustainable.

Since its inception, the practice has had a strong focus on construction and manufacturing. Court House is one iteration in the ongoing pursuit of a rational and efficient building system, and Archier has now established a fabrication arm called Candour, which will produce insulated panels as part of an end-to-end construction platform, including structural facade and glazing. This will allow future projects to be even less reliant on steel than Court House. Chris borrows a phrase from economics – “reducing the transaction costs” – to explain the efficiencies that lie in making their own system. Archier is the kind of practice that builders naturally adore, and the collaboration at Court House was so successful that the builder has since commissioned Archier to design his own house.

“We learnt from this project, and my house, and Ben’s house. As a studio, we are super interested in improving construction methodologies and processes to get to a better future. This is not primarily an aesthetic pursuit, if you know what I mean,” says Chris. For Archier, the Court House is a stepping stone to a better thermally, materially and fiscally efficient building and procurement process, but it is also an exemplar of rational planning and minimalist design. And importantly, it challenges conventional thinking about the preservation of, and value ascribed to, this country’s colonial built heritage.

Products and materials

- Roofing

- Klip-lok Classic 700 and galvanized Custom Orb sheets by Lysaght; 215-mm structural insulated panel system by Radial Timbers in ‘Silvertop Ash’.

- External walls

- Blackbutt fascia; cladding in ‘Silvertop Ash’; con-crete off-form blade wall columns; galvanized mesh; 115-mm structural insulated panel system.

- Internal walls

- Murowash paint from Murobond in ‘Sand’; Contours timber lining boards by Porta.

- Windows

- Frames by Binq; double glazing by Australian Glass Group.

- Doors

- Murowash paint by Murobond; SG15 honeycomb-core door by Hume; unlacquered brass hardware from Lockwood; timber-framed doors, tilt turns and lift slides by Binq; internal sliding door handles by Steel Road Custom Furniture.

- Flooring

- Hiperfloor concrete in low-exposure salt-and-pepper grind and 20-grit polish.

- Lighting

- Highline brass pendant by Archier; Cooper brass pendant by Coco Flip; LED track lights by Brightgreen.

- Kitchen

- Solid stainless steel plate benchtops; Lugano tapware from Par Taps in ‘Raw Brass’; Fisher and Paykel appliances; Monte Carlo rangehood from Whispair; laminate cabinetry in ‘Green’ and melamine cabinetry in ‘Black’ by Laminex; vertical timber lining by Porta; Blumotion with tip-on door and drawer hardware by Blum.

- Bathroom

- Terracotta tiles from Middle Earth Tiles; Inax tiles from Artedomus; tessellated tiles from De Fazio Tiles; tiles from Classic Ceramics in ‘Green’.

- Heating and cooling

- Central ventilation unit LWZ 370 Plus by Stiebel Eltron; floor-mounted reverse cycle by Mitsubishi.

- Other

- Cruciform columns and front path by Sheringham Construction; Number 14 chair by Bern Chandley (designer) and Chris Summons (builder).

Credits

- Project

- Court House

- Architect

- Archier

Melbourne, Vic, Australia

- Consultants

-

Builder

Sheringham Construction

ESD consultant RED Energy

Engineer Astleigh Consulting Engineers

Interiors Archier, Sarah Trotter

Landscaping by client

Lighting Archier

- Aboriginal Nation

- We acknowledge the traditional custodians of the land on which Court House is built.

- Site Details

-

Site type

Rural

Site area 5400 m2

Building area 220 m2

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Design, documentation 17 months

Construction 12 months

Category Residential

Type New houses

Source

Project

Published online: 11 Nov 2022

Words:

Tobias Horrocks

Images:

Rory Gardiner

Issue

Houses, October 2022