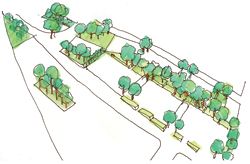

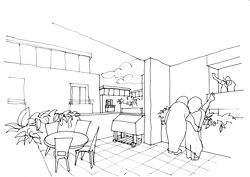

View of the proposed development looking south along Louis Street.

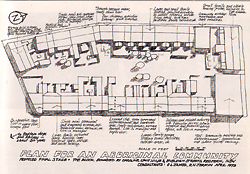

1973. First plans for The Block by Col James and Richard Jermyn.

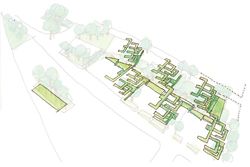

2004. Site plan of The Block’s residential area by Dillon Kombumerri. These plans form the basis for the final plans by Cracknell and Lonergan Architects.

2005. Red Square architecture and urban design. Proposal by Innovarchi Architects.

Proposed mixed use aerial view

Proposed public art sites

Proposed ground landscape

Proposed upper ground overlay landscape

View looking north along Eveleigh Street

View looking north east from residential apartment (second floor)

View looking north east from Caroline Street

Urban Aboriginal communities grow increasingly complex, with an extreme range of socioeconomic problems. As urban planners, architects, politicians and policy makers, we face the challenge of how to plan for sustainable Aboriginal communities. We need to broaden our understanding of why planning failures occur and learn from planning successes. We also need to re-examine planning frameworks to place Aboriginal ways of knowledge and values at the forefront. There are salient lessons to be learnt about Indigenous grassroots planning processes from one of the most notorious urban Aboriginal communities in Australia – “The Block” in Redfern, an inner-city area of Sydney.

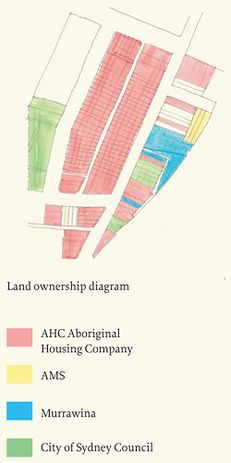

In the early 1970s, the lack of appropriate housing in the market led to the formation of the Aboriginal Housing Company (AHC) on a site of approximately 0.8 hectares containing around eighty-five dilapidated Victorian terrace houses near Redfern Railway Station. The federal Whitlam Government funded the acquisition of a group of houses with a grant that secured the first Aboriginal urban land rights in Australia and marked a period of genuine support and self-determination. With the assistance of architect Col James, the AHC began planning for the future of the community. By 1983 there was a thriving, cohesive Aboriginal community of approximately 400 people and a strong family network. The whole site was gradually acquired by the AHC, providing affordable rental accommodation to Aboriginal families.

In the 1990s, with the infiltration of a hard drug culture, heroin and its related criminal activity swept through the area. Within a decade, The Block became a location for transients, drug dealers, alcoholics and kids heavily involved in substance abuse and crime. Many of the original terrace houses were abandoned, demolished or used as shooting galleries.

The new millennium saw ongoing issues, which included inadequate and substandard housing, overcrowding, vandalism, crime, alcohol and drug abuse, drug dealers and criminal manipulation, homelessness, children and youth at risk and an unsafe environment. Many of the problems were caused by “blow-ins” from outside the Aboriginal community, while government neglect was substantially responsible for the situation on The Block. The Redfern riots of February 2004 were, in many ways, a statement of hopelessness, despair and rage from this urban Aboriginal community.

Over the past three decades, the AHC has attempted to redevelop The Block. The plans developed over that time have a common theme of community – each included affordable and safe housing, health, education and cultural facilities, and each promoted Aboriginal enterprise and employment. Now, in colloboration with community groups, local police and residents, the AHC has turned around the area’s bleak prospects with a strong Community Social Plan that creates a vision of a sustainable future for the Redfern Aboriginal community. The Block will be revitalized as an open residential precinct, which also retains and celebrates traditional aspects of Aboriginal culture. The active role of the AHC in preparing these plans demostrates the importance of the redevelopment to the socio-cultural transformation of the local community.

The AHC’s planning process maps the path to self-determination, governance, capacity building and leadership. However, the New South Wales Government currently obstructs that path, perniciously undermining Aboriginal self-determination, governance and its leadership. The redevelopment project will deliver positive outcomes for government and the Aboriginal community, yet the AHC has experienced systematic removal of government support structures, exclusion from area plans and withdrawal of funding. Not only has the government set a course to destroy any systematic approach to sustain and strengthen this community, but it has also proposed new planning mechanisms that could potentially disempower Aboriginal people, removing them from control over all but a small portion of their lives.

However, over the past few years, through the alliance of policy and planning advisors, the AHC’s redevelopment has closely integrated wider economic and social development planning. The plans are for a mixed-use development including commercial uses, recreational and cultural facilities, and family-oriented housing, and are consistent with the new Built Environment Plan and State Environmental Planning Policies. Concept plans developed by Aboriginal architect Dillon Kombumerri formed the basis of the final Pemulwuy Project plans prepared by Cracknell and Lonergan Architects. Due to the incredible amount of work by and the generosity of Cracknell and Lonergan and various other planning consultants, the final project application was submitted in October 2007. This was a momentous occasion – the first comprehensive, mixed-use development plan to be submitted for The Block after more than thirty-five years of plans.

The development is approximately 40 percent residential and 40 percent retail and commercial, with 20 percent devoted to cultural, community and recreational activities. The spatial organization shows the six three-storey, multi-unit apartment buildings arranged around a series of gardens, forming a single block bounded by Eveleigh, Louis, Caroline and Vine Streets. Designed to be able to be sold as strata-titled units, the variety of housing includes: twelve four-bedroom dwellings on the lower ground level, twenty-four two-bedroom units on the upper ground level, twenty-two three-bedroom dwellings and four one-bedroom apartments, with terraced private open space. The development proposes a cultural centre at the northern end to house an Aboriginal Elders Community Centre, with 46 percent of the site to be private outdoor space. The new Redfern Gym will be at the southern end of the development, having existed on The Block for twenty-five years. The plan also includes a health and respite centre, fronting Caroline Street – a commercial development in association with the Aboriginal Medical Service (AMS), providing respite care for non-residential patients and family members who travel to Sydney to visit the AMS or other Sydney hospitals. Existing laneways will be incorporated into the development, though in the past laneways have been a safety and security hazard. Countering this, the development includes open space and mixed-use buildings for commercial and cultural activities, including an art gallery and ancillary retail. The project will be delivered as a staged development, with the concept master plan for the whole site being followed by subsequent individual project applications for specific sites.

The Pemulwuy Project offers to rejuvenate the Redfern area. As Cracknell and Lonergan wrote in the project description: “The construction of this premium-quality mixed-use development will increase commercial and residential densities around Redfern Waterloo, and in particular the transport hub of Redfern station, in a manner consistent with the Sydney Metropolitan Strategy. It includes vital employment-generating commercial activity and medium-density family-style housing, which is urgently required for Aboriginal people close to the city.”

The AHC redevelopment project offers an opportunity to challenge how we think about Indigenous planning. There are valuable lessons to consider – Indigenous participation in the planning process and the central role of the community in devising and implementing strategies; effective collaboration and an enabling environment that allows effective structures to be developed; constraints to radical intervention; effective Aboriginal decision-making and governance; and Indigenous rights.

The Pemulway project is a prime example of the local community both contributing to and using knowledge. It demonstrates applying Indigenous Knowledge (IK) in the development process, building partnerships and integrating IK practices in the design and implementation of development activities, and finding relevant and realistic solutions to the development problems on The Block. In essence, the AHC planning process has placed Aboriginal knowledge and values at the forefront. It has achieved a new form of Indigenous governance and Indigenous planning.

This project is significant for Indigenous people who are fighting back against the invasion of their communities by mainstream planning policies and political agendas. The future of Indigenous community development lies in the creation of legitimate planning structures to facilitate sustainable development from Aboriginal perspectives. Taking the lead from the international community, some future directions could include establishing a national Indigenous community housing enterprise, with a focus on home ownership (modelled on Canada’s National Aboriginal Housing Association) and creating a national Indigenous planning association (based on the Indigenous Planning Division of the American Planning Association).

Building on Indigenous planning in education and social learning is a key component in its success. Planning educators and scholars Nicole Gurran and Peter Phibbs ask how educators and researchers should support these new forms of governance and Indigenous planning opportunities:

“A first step is to ensure that planning education is accessible to and appropriate for Indigenous students. Other pedagogical questions that concerned us were how to design effective and ethical ways of teaching Indigenous Knowledges and concepts of environmental management; and, how to assist our students with the critical understanding of planning needed to develop new approaches more attuned to cultural diversity in general and Indigenous cultures and needs in particular.”1 Building on structures that encompass Indigenous planning in education and secure institutional means will promote greater Indigenous participation and control as well as creating a climate responsive to Aboriginal concerns. Professional institutions such as the Australian Institute of Architects and the Planning Institute of Australia can provide a means for transmitting, accumulating, enhancing and transforming IK and planning systems. We need an Indigenous planning structure based on inclusivity and connectivity rather than exclusivity and autonomy. Reclaiming the right to plan their own communities may have powerful political, economic, social and environmentally sustainable consequences.

Angela Pitts is a PhD candidate at the University of Sydney in the Faculty of Architecture, Design and Planning. She is also a social planner with the Aboriginal Housing Company and author of the national and international award-winning AHC Community Social Plan.

1. Nicole Gurran and Peter Phibbs, “Indigenous Interests and Planning Education: Models from Australia, New Zealand and North America”, in ANZAPS Conference (Perth, Australia: 2004), p.2.

THE PEMULWUY PROJECT

Architect and heritage consultants

Cracknell and Lonergan Architects.

Landscape

Paul Scrivener Landscape Architect.

Legal and planning

John Mant, Justin Doyle.

Social planning

Angie Pitts (CPTED consultant), The Aboriginal Housing Company, Col James.

Planning

Richard Smyth, Space Syntax – Martin Butterworth.

Environmental management

ABC Planning.

Traffic consultant

Traffic and Transport Planning Associates.

Infrastructure – water

Parsons Brinckerhoff.

SEPP 55

Urban Environmental.

Surveyor

Denny Linker.

Other consultants

RedWatch – Geoff Turnball, Redfern Police.