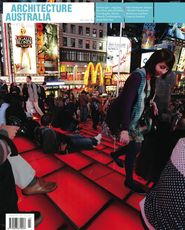

Installation view, with Marcus Trimble’s blog Super Colossal on the left. The back wall shows Choi Ropiha’s Ballast Point Park, Sydney, and the TKTS booth in New York. Photography Murray Fredericks, courtesy of Boutwell Draper Gallery, Sydney.

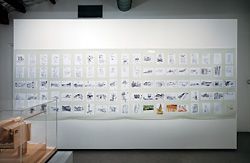

Sketches and diary entries by Angelo Candalepas.

Models of Terroir’s Castle Cove House.

Installation view: panels by Dale Jones-Evans on the left, exploratory drawings by Peter Stutchbury on the right and Lacoste + Stevenson’s A3 sketchbooks in the foreground, with Terroir’s models on the far wall.

Doubt, curiosity and process. Laura Harding reviews a recent exhibition at the Boutwell Draper Gallery.

There is a palpable tension present when architecture is exhibited in a gallery. This tension is important – if it is absent, it is because the magic of architecture’s physicality, its changeability, its tactility and pleasure has been blunted or stifled in a desire to frame it within the more exclusive realms of art. Architecture 09, an exhibition of the work of nine architectural practices at the Boutwell Draper Gallery in Sydney, presented a range of architectural artefacts that aggravated and amplified this tension.

Tom Heneghan’s beautiful accompanying essay spoke of the almost guilty passion that architects have for the remnants of their exploratory work, particularly their loose, swift sketches and working models. They are revered, mysterious and talismanic. He writes, “The paper trail tells us about ourselves and how we think. In a way, our sketches are self-portraits.” Viewed in this manner, the contents of the exhibition were extraordinarily revealing – perhaps much more so than realized architectural works.

Terroir colonized a wall with an elegant series of folding, canting and shifting cardboard models of the Castle Cove house. Each seemed to multiply and morph like an organism, from 1:500 to 1:100 to 1:50, stealthily encroaching upon the confines of the gallery wall. While captivated by these extraordinary models, one imagines the onset of a perverse sadness for the architects at the moment of actual, physical construction – when form becomes fixed in reality and the restless exploration of the project is necessarily halted.

Choi Ropiha revelled in the exploratory nature of construction, with a series of sketches, fragments of documentation and photographs of pavilion elements for Sydney’s Ballast Point Park and the TKTS booth in New York. Especially engaging were images of the architects in the steel fabricator’s workshop – capturing that moment of terrified wonder, acutely familiar to all architects, on encountering the sketch in physical form for the first time.

Marcus Trimble displayed the entire contents of his wildly successful blog, Super Colossal – his quirky, informal and responsive record of architectural culture. Trimble’s curiosity and agitation of a broader architectural culture are utterly infectious, and a visit to his website is a mandatory part of the daily routine of many practitioners.

Angelo Candalepas displayed his personal passion for learning through drawing from architecture – presenting a series of exquisitely rendered sketches and diary entries of his visits to the work of Bramante, Aalto, Scarpa, Kahn, Gaudi and Coderch. Recording painstaking detail in fine graphite, fleeting impressions in ink and vivid tactility in brilliant watercolour – the drawings felt alive. His sincere and fastidious study of the work of the masters is fundamental to the evolution of the work of his practice. This was demonstrated in a series of fine timber models that accompanied the sketches.

Peter Stutchbury, faithfully rendered in a red pencil portrait by his daughter, hung a series of his exploratory drawings of place. There is not a single superfluous mark in these drawings and despite their highly personal quality they have an extraordinary ability to convey to others an atmosphere of place. A series of black-and-white photographic images by Michael Nicholson emphasize the contradictory distance and proximity between the sketches and the realized work. The calm beauty of the photographs belies the intensity of the projects’ design and making – but their piercing clarity directly references the acuity of the very first marks on paper.

Humble and engaging in spirit were the twenty volumes presented by Lacoste + Stevenson – a series of serviceable A3 sketchbooks left open for perusal that offered visitors a tiny insight into the banal and breathtaking minutiae of practice. Each held a compilation of sketches and records from many different hands – exploratory drawings attempting to wring out the hidden logic of construction details; scraps of yellow trace that were salvaged, torn and taped into the semblances of ideas; tiny diagrams littered with dimensions and sums; and colourful site plans ringed with ideographs. Amongst these, the hastily stapled business cards of project consultants, fragments from phone calls and meetings – “if we get rid of accessible toilet, do we need a section 96?” – and snippets of faxes, emails and mark-ups. Lacoste + Stevenson aptly note, “They never were meant to be shown or pretty. This is what makes them worth showing.”

The work of Smart Design Studio, Dale Jones-Evans and LAVA (Laboratory for Visionary Architecture) was less candid, comprising highly resolved and stylized images of performances and projects that left less room for engagement and contemplation. Glossy and self-assured, these projects were presented with a confident, corporate sensibility – concealing the more personal reflections on work and practice that the other contributions afforded.

Juhani Pallasmaa notes that, “The understanding of identity, the prerequisite for creative work, comes through a tolerance for – actually an engagement with – silence, solitude, even boredom … and uncertainty.” It was the honest revelation of uncertainty, doubt, trepidation and curiosity in the working process of these architects that was the most compelling characteristic of Architecture 09. This candour is a welcome reprieve from the illusory perfection with which architecture, in its highly mediated form, is now almost exclusively endowed.

Laura Harding practises with Hill Thalis Architecture + Urban Projects.